Who is the ‘literary it girl’? According to the internet, she’s the literati’s answer to the question of cool — a question which has plagued us for thousands of years, since Plato first debated the virtues of the active versus the contemplative life. How to live the life of the mind and yet stay engaged with one’s community, to think and read and write and still find status and fame in social life? Or, to put it more prosaically: how to be a hot nerd?

The literary it girl is a hot girl — but not too hot. She makes it look effortless, edgy. She boasts a handful of publications and a forthcoming collection with a cover like a stylish coffee-table book. She lives in one of a handful of North American cities, probably NYC, but her relationship to the urban sprawl is one of distanced irony. She’s fond of irony in general, in fact, it’s her default mode. She’s an intellectual out on the town, frequenting gallery openings and book launch parties and runway shows, but she’s also terminally online, plugged into the glowing blue current of the internet. She’s on topic; on trend. She always has a witty quip to hand, on page or screen. She exudes effortless cool — a modern kind of studied sprezzatura. Perhaps that’s why she idolises Joan Didion and Eve Babitz; she keeps The White Album on her bedside table, along with a pack of cigs and a niche indie perfume.

She only exists as a figment of our imaginations, in the hallucinatory collective consciousness of the internet, created by clever marketing teams and micro-trend forecasters and the churning floodwater of discourse on Twitter and TikTok. She isn’t real — but we’re obsessed with her anyway.

It is Didion and Babitz who launched the latest round of ‘girl discourse’ — a topic I keep thinking we’ve escaped but which continues to rear its well-groomed head — when publisher Emily Polson tweeted a photo of Lili Alonik’s new book Didion & Babitz with the caption ‘Literary It Girls™ get ready’. Polson’s post sparked a contradictory response, with some suggesting that lumping two very different female authors together under one deeply reductive term could be considered sexist, whilst others pointed out the archival basis of the work and the many real world overlaps between the two. For full disclosure, I haven’t read Alonik’s Eve’s Hollywood, credited with restoring the writer’s reputation, nor have I secured a coveted review copy of Didion & Babitz (despite best efforts). In fact, I’m less bothered about the book itself, a fascinating sounding investigation of the pair’s ‘mutual attractions—and mutual antagonisms’ based off newly discovered letters, than the online climate that this discourse serves as a litmus test of. Nor do I think we should blame Polson for deploying a trendy term in a semi-ironic way to promote the work to a particular subset of extremely online and literary young women.

We saw the seeds of this discourse start to sprout last year, when a photo of a girl reading Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking on the beach went viral. As Laura Pitcher wrote for Nylon, ‘physical books have become a form of social capital online — held as photo props or perhaps even accessories’, with paperbacks popping up on our Instagram feeds and celebrities like Dua Lipa starting book clubs. Coupled with the rise of BookTok and the exponential growth of dark academia, which I wrote about earlier this year, it’s clear we’re in the reading renaissance and women are at the forefront. No wonder everyone wants to capitalise upon it, the latest instance of which is Taylor Swift’s cringe-inducing ‘The Tortured Poet’s Department’ marketing campaign, featuring a pop-up library full of ‘academia props’. Vogue even labelled her the ‘Literary It Girl of the pop charts’.

None of this is strictly a bad thing — if anything, it’s refreshing to see women moving away from the self-infantilising girlhood culture of the past couple of years and embracing markers of intelligence and artistry. Yet at the same time it speaks to our desire to consume surface level content rather than engage meaningfully with art, and to the image-obsessed online world which sees the book as a commodified marker of status increasingly adopted into the ‘hot girl’ arsenal.

It ironic that the notoriously private Joan Didion has become the idol of the online girl literati, sometimes to the point of parasocial obsession. In a recent piece in Architectural Digest on celebrity estate sales, lifestyle influencer-turned-model-turned-poet (and my 2017 icon) Orion Carloto described purchasing a quilt formerly owned by Joan Didion for $8000. Carloto’s reported motivation for her purchase was ‘to feel closer to Didion and feel her presence in her home’. Was a shelf of her books not enough? Our literary idols can’t just be literary, they have to be tangible, embodied in totemic objects like Didion’s rug or her signature sunglasses. This focus on the visual and the material depicts the writer as a kind of content creator, the adulation of whom involves a wholesale buying into (and in Carloto’s case, buying of) their persona and lifestyle. Such an elision between ‘creative’ and ‘content creator’ sells us the idea that being a writer, academic, or thinker is just another kind of aesthetic choice you buy into and then drop when the next big thing comes along.

As A. V. Marraccini writes in their electric manifesto ‘Hephaestus Contra The It Girl’: ‘The It Girl is them selling you the idea of the thing you are supposed to want to be.’

So whilst this new turn towards intellectual aesthetics might be an attempt to give girl discourse a more substantive base, it feels equally as reductive. We can’t just be writers; we have to be girl writers, in which girl is conjoined to an invisible adjective: hot. Or at least, we have to package ourselves as such. Because otherwise why would anyone want to read our work?

It’s impossible to take a lunchtime walk through Mayfair without wandering into the back of a TikTok interview. Most of the time I dodge the cameras like a sardine in sight of a veneer-toothed shark, but there’s a tiny part of me that actually wants to get trapped. What would I say? I’m a writer and researcher currently working in a gallery whilst waiting to start my PhD. Does that make me sound interesting? I’ve practiced the line — I turn it on at parties and when meeting new people. Would the interviewer ask for my full name, for the name of my blog? Would I gain new readers? Would my wry delivery and effortless, writer off-duty attire (cashmere sweater and long black trench, pearl earrings and jet signet, for the sartorially-enthused) catch the eye of some agent or editor doomscrolling on the bus?

We — I — want to believe there’s a shortcut to success. We want to believe we can make it, both artistically, socially, and financially. That we can live for our craft and perhaps come to live off it too. We romanticise the literary milieu of America in the 1960s and 1970s because it presents us with a golden age of the writer, much in the same way the 1920s do (those New Yorker lunches at the Algonquin!). Reading about Didion’s legendary Easter parties or the ease with which Babitz cruised from champagne-and-cocaine lunches to meetings with her agent fills us with envy, a sense that back then at least writers and artists could have their cake and eat it too. The 70s were a time when writers were cool! Yes, they were wildly talented, but they also lived in a world which appreciated them and their work. It’s the same envy that grips us when we watch 90s and noughties rom coms, so many of which feature writers and journalists. Carrie Bradshaw gets an infinite shoe closet off the back of one hastily dashed-out column a week, and how on earth can Bridget Jones afford that flat?! These are our literary it girl archetypes — they don’t have to choose between a social life and the life of the mind. They can have both. In fact, their having both is integral to their work. Who would Carrie Bradshaw, or for that matter, Eve Babitz, be without her diary full of party and dinner invites?

It doesn’t work like that anymore, if it ever did. In the 2020s it feels increasingly punishing to survive as a writer, let alone build a real world community centred on art and ideas. Soaring costs, falling wages, unpaid labour and the threat of AI, as well as the lingering aftershocks of the pandemic, to name but a few factors, have made it increasingly difficult to earn a living without vast generational wealth, nepotistic connections, or your writing being some kind of side hustle to a full time career. It’s why the recent discourse about media parties rubbed me up the wrong way. Sure, New York media parties might be boring, but least you’re getting invited!

Even when we can establish a ‘platform’ or ‘following’ (note again the elision of writing and influencing), huge swathes of time must be dedicated to marketing ourselves and maintaining that platform rather than the actual acts of research and writing. We have to market ourselves, package ourselves into corners of the internet and carefully cultivate our social medias. We have to learn SEO, play into the algorithm, know the right tags to use, the right time to post. We can’t just strive to be writers, we have to strive to be literary it girls too.

Does this reek of jealousy? Perhaps it does. I’m willing to admit that I envy the writers who started online and now get profiled in indie magazines and invited to parties or readings or gallery opening nights. The women who have elegant author photos and shiny websites and tens of thousands of followers on Twitter, who get paid subscribers on Substack without ever posting so much as a Note. When my friend says ‘You know you’re kind of Twitter famous’ (I’m not) in front of her new partner, I allow myself to feel good about it. To toss my hair and say something like ‘Well, I’m really more of a niche niche niche internet microcelebrity’ — as if these buzzwords mean anything, as if they relate at all to my craft and the way it defines my place in the world. But that doesn’t matter. All that matters is that someone else — someone new, the sort of someone I might encounter online — knows me as a writer, and that this is something cool. Because I want to be a literary it girl. I want nothing more — and that’s part of the problem.

When we strive to be something that doesn’t really exist, that is nothing more than the figment of the algorithm’s imagination, we can compromise our originality, risk our authentic voices and artistic development being subsumed by the tidal wave of content and conversation that we have come to call the discourse. There is no stable footing in the discourse. It is the morass which is left after a flood, a volatile landscape in constant flux, punctuated only by a few stable landmarks which we cling to. We try to grasp these trends whilst they are still above water and find ourselves in search of virality whether we want it or not, rehashing the same tired topics. Forgive me, I am doing it now! I am writing my third essay about girlhood in twice as many months! Yet is there lasting power to my words? By the time this essay comes out, the literary it girl discourse will be almost over. We’ll have moved on. The whole thing will be cheugy — a word which, ironically enough, is now itself cheugy. I worry about this all the time, as my own work moves increasingly away from fiction and towards interdisciplinary criticism. Am I just jumping on the bandwagon, writing another quasi-personal essay about a trending topic, when that simply skims the surface of my interests? But how can I not, when my rapid responses to trends, memes, and internet culture rake in double the views of my more considered, philosophical pieces. When the whole format of Substack itself has changed in favour of the social, prioritising the expansion of Notes in an attempt to rival X-formerly-known-as-Twitter. Am I doing my best work here? I don’t know. Because I have no time or energy to create other work, to enter the punishing mill of pitch and rejection or to write outside the momentum that enables me to keep ‘building my brand’. Because I am constantly in search of cool.

When we hold up the literary it girl as our idol, we’re not just doing a disservice to decades worth of female writers who can and must be defined by so much more than their image. I don’t necessarily care that much what the literary it girl label does to Didion’s work, or Babitz’s, or the many other luminaries to whom the term has been applied. I care more about what it does to young female writers today, developing our voices and defining ourselves in a world which both requires and reviles us, which currently sees us as a trending topic but may drop us as soon as the moment passes.

In a now-deleted Tweet from earlier this month, a woman asks for recommendations of ‘Glamorous 20th century experimental writers’, citing Clarice Lispector as an example. The replies are full of black and white images of women writers, usually white, conventionally attractive, well-dressed and likely wealthy. ‘Added to the reading list!’ users reply, off the back of a elegant headshot, or ‘heading to the bookshop now!’. Others reacted with scepticism: should we really be judging these groundbreaking women by their appearances, when the very nature of the written word (in experimental fiction in particular) strives against such a shallow, surface-level summation? When women are already judged by their physical appearance in every aspect of life?

The author of the Tweet may not have intended responses to be based solely on physical appearance, but that’s the direction the thread took. Babitz, often seen as the archetypal literary it girl, is quickly rejected; she doesn’t have it. It’s hard not to tie this to her physical appearance, which despite her famed sensuality and ‘voluptuousness’, appears plain to a twenty-first century audience. Equally, using Lispector as an exemplar feels particularly egregious, given the aspects of human experience her work is so concerned with. In The Passion According to G.H. an artful, artistic woman is forced to shed layers of ‘humanisation’ as she gains access to the raw core of things at the heart of life and death itself. The ‘first freedom’ G.H. experiences is that of realising she no longer ‘respected beauty and its intrinsic moderation':

I must have lived so imprisoned to feel free now just because I no longer fear the lack of aesthetics…For now the first timid pleasure I am having is realising I lost my fear of ugliness. And that loss is such goodness.1

The ‘fear of ugliness’ and desire for elegance is part of what has kept G.H. tethered to the ‘humanised’, socialised life which she comes to see as shallow and meaningless. Meanwhile, in The Hour of the Star, the plainness and ordinariness of the hapless Macabéa is emphasised, yet it is this ordinariness which makes her individual life such an extraordinary tragedy rending the very fabric of reality in twentieth-century Brazil. Lispector’s heroines are not glamorous it-girls, and we must resist categorising her deeply complex works in this way simply because of her striking physical appearance.

When I look up my favourite writers — Rachel Cusk, Chris Kraus, Hilary Mantel, Olivia Laing, the list goes on — they are unremarkable looking, middle-aged. Yet their work dazzles me, snares me in and spits me out entirely changed. It is, in the truest sense of the word, glamorous. Not glamorous in the sense of beautiful or ‘aesthetic’, but in its archaic form, drawn from the Scots glamour, meaning magic, and the Middle English grammar, which referred interchangeably to language and magic. Grammar’s Latin root, grammatica, means simply ‘skilled at writing’. Myth-making, magic, and the written word are woven together and transmuted into beauty, desirability, the construction of an elegant artifice through unnatural means. To weave a separate world out of words is the writer’s craft, much as it is the archaic magician’s. Yet in our image-saturated age of information overload, we have come to focus narrowly on glamour in its hollowed-out modern usage, more commonly used in glossy magazines than grimoires. Writers are glamorous, but not because of the arch of their brow or their signature lipstick.

Many of the women I admire write autofiction (itself frequently seen as a feminised form of writing) or non-fiction infused by biography, and from their works we know they are desired, desiring beings. Perhaps most famously, Kraus relates in thinly-veiled detail about her failed love affair with cultural theorist Dick Hebdidge (another regular reference on this blog) in her aim to ‘tell The Dumb Cunt’s Tale’. Though of course, Kraus is anything but dumb. But throughout I Love Dick her authentic self — whatever that is — is trapped between two archetypes. She is either an intellectual removed from her body, engaging in desire simply as an art project, or lustful, wet, a Dick-mad ‘Dumb Cunt’. Either / or. Where does her glamour sit? Somewhere in the middle, in the writing which attempts to bridge the two.

As

reminds us in her brilliant and much-cited essay ‘Everyone’s Writing Sounds the Same Now’, ‘if enough young women like something, it’s about to get majorly cringe.’ Our patriarchal culture loves to demean young women as frivolous, over-emotional, and irrational; this has been the case for literally hundreds of years. The pendulum has swung so rapidly from bimbocore, coquettes, and ‘just a girl’, that we have to wonder what’s next. Microtrends have little staying power, and are subject to the whims of the algorithm; an impermanence in striking opposition to the considered, slow, hard work of research and writing. It’s difficult to keep sight of that hard work when aspiring writers have to perform a different sort of work, branding themselves against the standards set by lifestyle influencers taking snaps of paperbacks on a private beach, or a multi-millionaire celebrity coopting the aesthetics of the ‘tortured poet’ for a global ad campaign without upholding the voices of actual poets, including those suffering real oppression in Palestine and elsewhere. Here is writing as an effortless aesthetic, a self-centred lifestyle, increasingly feminised — and therefore easily viewed as trivial, bogged down in shallow concerns over image and ‘glamour’ and wealth and reputation.So have we already hit peak literary it girl? And if so, where next?

I was thinking of this during the recent furore over Lauren Oyler’s new essay collection No Judgement, which has been widely panned, particularly by her fellow ‘it girl critics’ in what has been called a ‘brutal bloodbath’. Some people have suggested that Oyler has been ‘woman’d’ (‘when everyone stops liking a woman at the same time’, a term coined by

, herself often labelled a literary it girl), though it sounds to me more like Oyler’s book is just plain bad. I do worry that we’re moving in a harmful direction though, where we don’t just expect young female critics or thinkers to provide insightful, well-researched criticism, but ‘takedowns’ and ‘hot takes’, to provide a bitchy catfight worthy of Selling Sunset or Real Housewives, a feminised performance of gossip and secrets and spite. When we tweet ‘the girls are fightinggg’ and tune in for the next round of reviewer wars, the next personal essay from The Cut to rip apart, we don’t just want to read good criticism. We want to see blood.As

put it on Twitter:how much of all this critic-on-critic violence can we directly attribute to the phenomenon of becoming a literary it girl requiring the calculated decision to brand oneself, in both reputation and in one's own writing, as a hot girl

I worry that if we’re not careful, writing by women itself, not just individual female writers, will be ‘woman’d’. If it gets too messy, too ugly, too unlikeable, too boring, if it starts to sound the same, or worse, if it sounds just a bit too different. If it’s no longer hot, no longer on trend, when it loses the ‘it factor’ and goes back to just existing.

In today’s culture of hyper-accessibility and instant gratification, we expect our thinkers to be available to us online, not just as writers, philosophers, or critics, but as individuals. Shortly after I wrote in my last essay about Byung Chul Han, the New Yorker designated him ‘the internet’s new favourite philosopher’, and noted his notoriously illusive, private presence, suggesting that Han’s ‘status as a kind of philosophy daddy to a younger generation is reinforced by the scant glimpses that readers get of his personal image’. As this suggests, we desire ‘glimpses’ which offer an insight into the person as much as the philosopher, but Han has maintained his offline presence, even as he writes about the negative impacts of the online world. Is it a privilege of Han’s maleness which enables him to live a life of utmost privacy, to put into practice his thinking? I think of women who’ve written about the corrosive impact of the internet (Patricia Lockwood, for example, in the realm of fiction) and how we still anticipate an online presence from them, a snappy viral tweet in response to the latest discourse. We want to see them wade into the bloodbath and get their hands dirty.

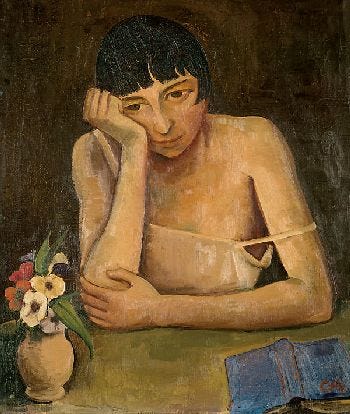

In the world of letters as well as the world at large, we expect women to be more available to us, more accessible than their male counterparts. We want to be able to own a piece of them, to hang it, like Carloto, on our walls. Under patriarchy, women are taught to present ourselves as commodities, and this influences our self-presentation in the public sphere — think of those perfectly contrived black and white author photos. Think of Lispector’s G.H., shedding her ‘fear of ugliness’ only through confrontation with the abject. Think of Babitz, nude at a chess board opposite Marcel Duchamp. We want full access to a female artist’s body as well as their output. We demand it. We cannot let them prioritise the life of the mind when they are tied to the flesh. They must be either / or, contemplative / active — remote and erudite Joan Didion, hidden behind her sunglasses, or Eve Babitz, always seen as ‘too sexy and too lightweight to be serious’.

We might think we have escaped this paradigm, the mythmaking dualisms which constrain women to certain ossified cultural roles. And yet. We seem trapped in the same patterns, forced to pigeonhole ourselves into categories or embracing those same categories through a thin veil of irony. We are ‘sad girl novelists’ or ‘tortured poets’ or ‘literary it girls’. Girls who are writers, women who are writers. We may think we’re moving away from the patriarchal assumptions of past centuries and the reductive self-infantilisation of the past few years, but we still cannot simply be. Writers first, or girls?

Think of Eve Babitz at the chess board, playing. We never consider that she might be about to win.

Clarice Lispector, The Passion According to G.H., p. 12

so glad someone really delved into the literary it girl, it's a topic that has left a bit of a sour taste in my mouth especially bc i feel like it's sort of dark academia made edgier. thanks for writing it !!

thank you for compiling everything I've been thinking for the last several months since I started writing "for real" on the internet