dating in the digital panopticon

red flags, boyfriend tests, and commodifying romance online

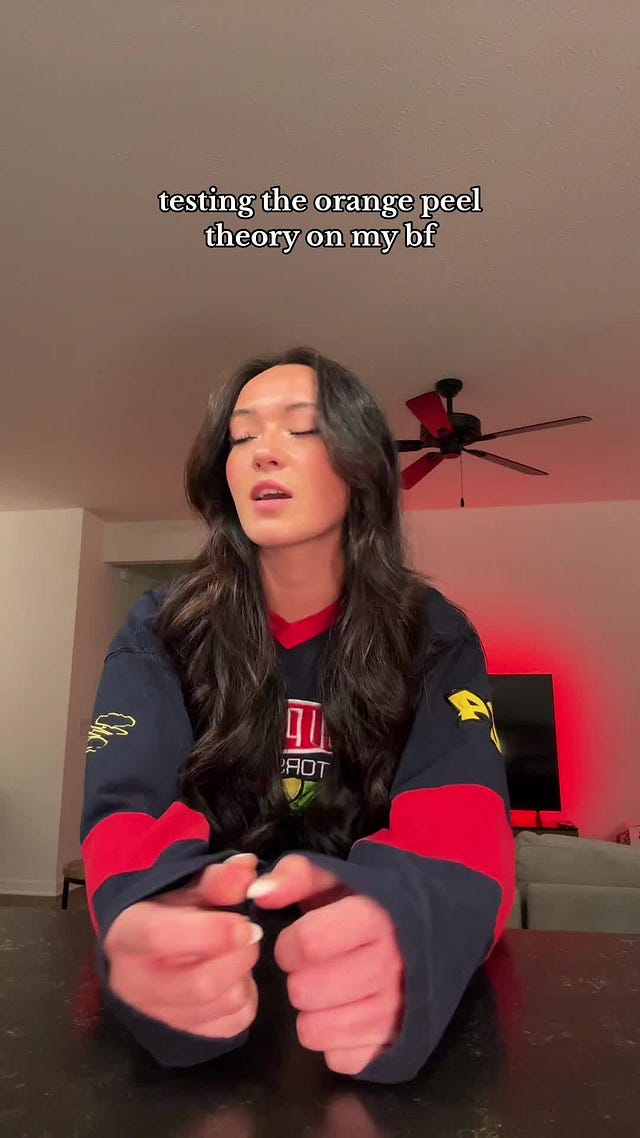

According to orange peel theory, which went viral at the start of this year, you can ascertain the level of your partner’s love and commitment by asking them for an orange. If they hand you an orange, okay, sure, they passed. If they plate up the orange, one grade better. If they peel it for you first, then congratulations! Flying colours, distinction, gold medal, etc etc etc. If your lover has done this well, they might as well go one step further and feed you the orange, segment by golden segment, whilst you recline in leisured state like Cleopatra in her bath of milk and honey.

If they raise an eyebrow and say: ‘My love, are you in engaging in another viral internet trend in order to prove some sort of point about the status of our romance, a habit which is tied to your competing impulses towards a) proudly and zealously exhibiting your ‘green flag’ relationship where ‘green flag’ means ‘does everything I want’ and b) asserting yourself as an activist ‘testing’ our relationship in a way which claims to be a feminist takedown of the patriarchy (which you fear you have bought into by dating a man) but is in fact the tiniest gesture of interpersonal spitefulness, because it sounds like you are. And besides, I don’t have an orange to peel for you. Wait — have you got a camera hidden in that fruit bowl?’, they have definitely, manifestly, 100% not passed.1

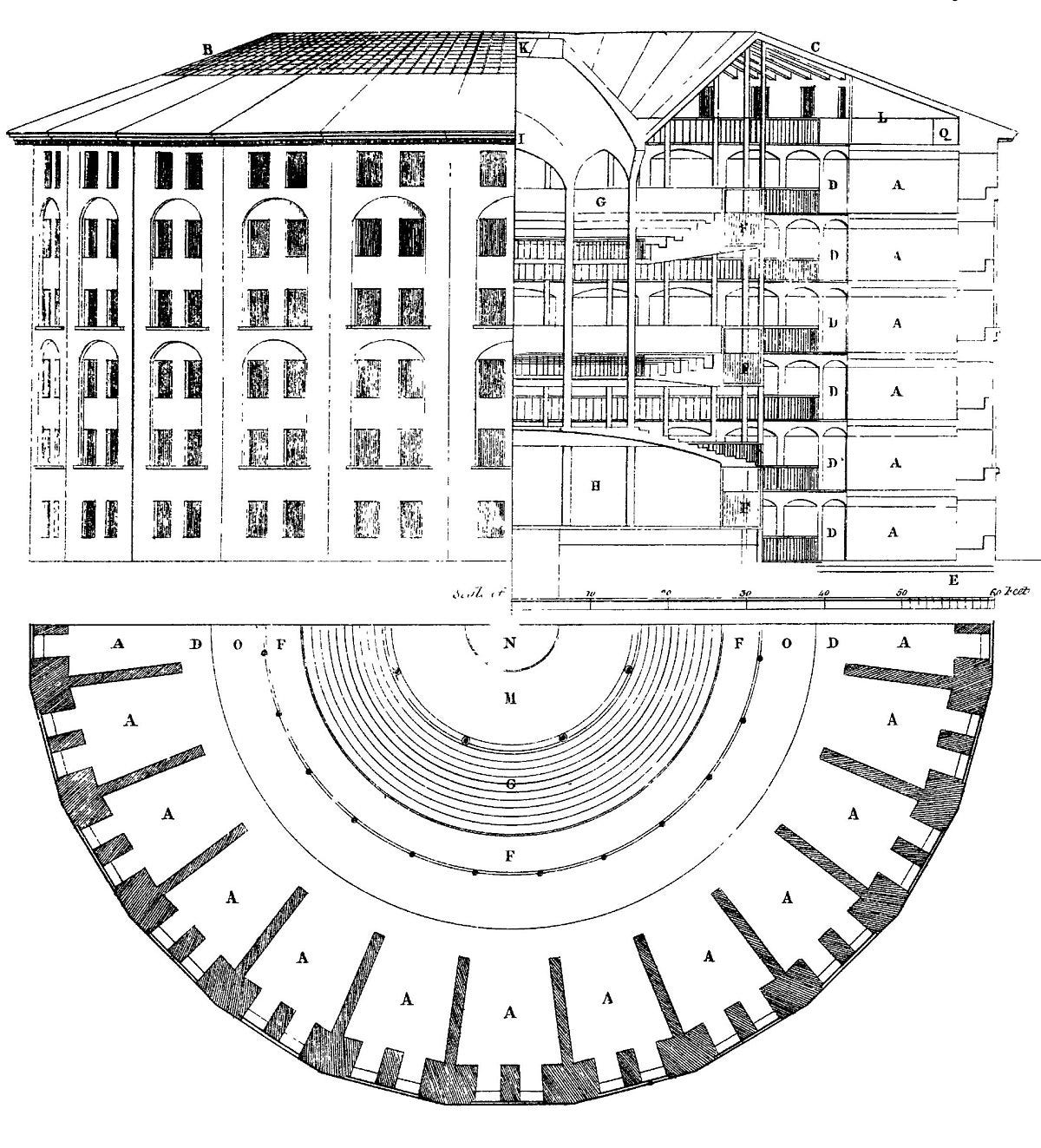

According to philosopher Byung-Chul Han, modern life is defined by an obsessive emphasis on transparency. Han argues that under the influence of neoliberalism and new digital technologies, total transparency risks the erosion of negativity, ambiguity, and depth in cultural life, shaping a shallow, homogenised, productivity-driven culture which rejects critical thinking and ultimately stabilises rather than challenges the status quo, translating the promise of freedom into control. Drawing on Jeremy Bentham’s infamous panopticon, a circular prison in which prisoners are isolated from one another but can at all times be observed by a central authority, Han argues that ‘Today the entire globe is developing into a panopticon’.

There is no outside space. The panopticon is becoming total. No wall separates inside from outside. Google and social networks, which present themselves as spaces of freedom, are assuming panoptic forms. Today surveillance is not occurring as an attack on freedom, as is normally assumed. Instead, people are voluntarily surrendering to the panoptic gaze. They deliberately collaborate in the digital panopticon by denuding and exhibiting themselves. The prisoner of the digital panopticon is a perpetrator and a victim at the same time.2

In relating the panopticon specifically to the digital world Han makes a crucial differentiation with earlier applications. The ‘prisoner of the digital panopticon’ has opted in to her imprisonment, she is a collaborator with the regime as well as a ‘victim’. She is a prisoner but she thinks she is free, and centralised coercion is not required as she engages in ‘voluntary self-illumination and self-exposure’, most notably through the medium of the internet.3

Han’s ‘digital panopticon’ illuminates the online world we have all come to inhabit. We all engage in self-disclosure and self-surveillance, whether we’re posting selfies on Instagram or personal essays on Substack. But we don’t just exist as individuals, complicit and self-surveilling, within this system of entwined transparency and control. We form, maintain, and display our interpersonal relationships within it too, whether we’re soft launching our new lovers, subtweeting our situationships, or engaging in viral ‘boyfriend tests’ like orange peel theory. We’re all dating in the digital panopticon.

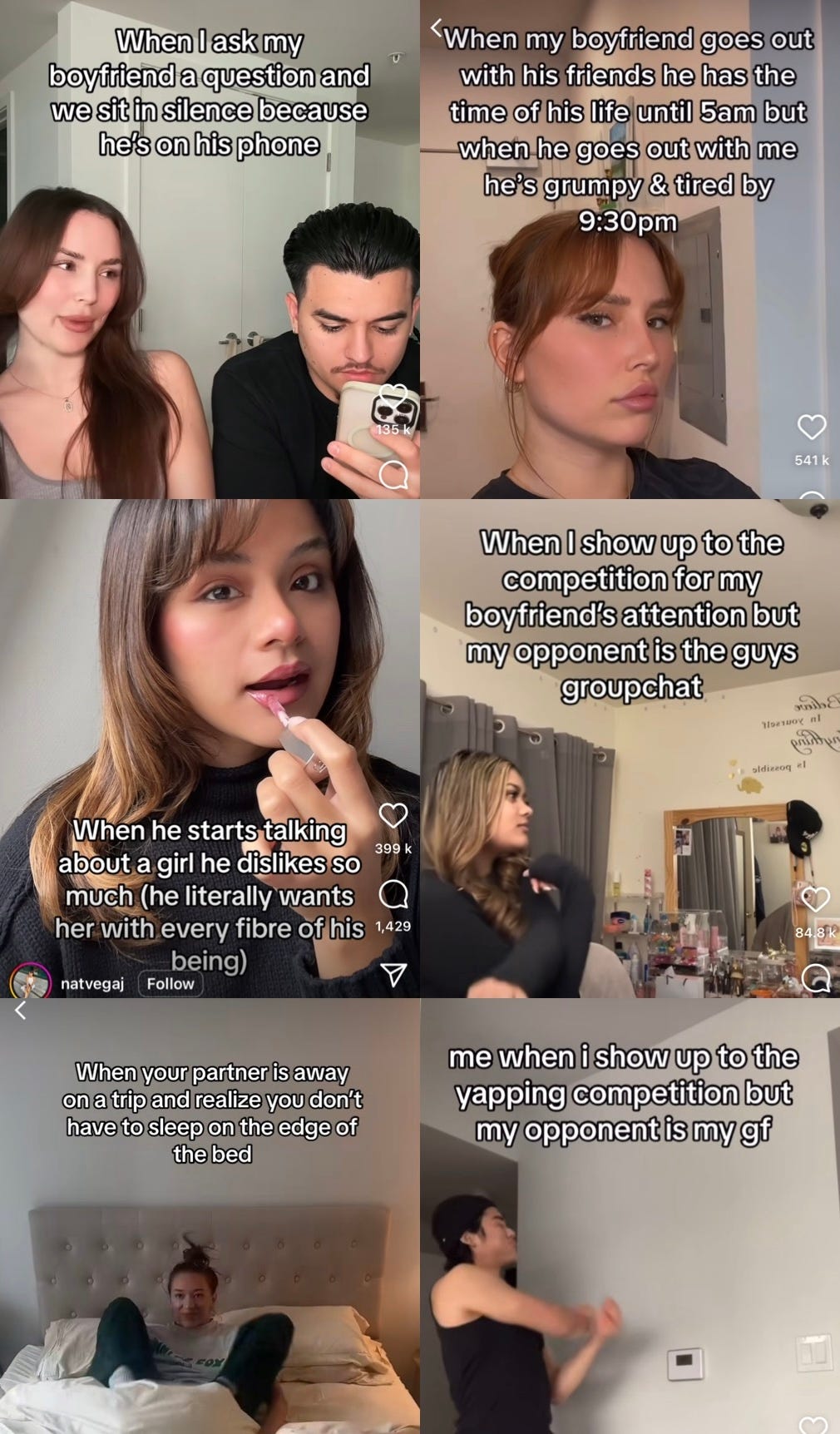

When did it become cool to dislike the person you’re dating? And not just to dislike them, but to obsess over and document their every flaw for a potentially infinite audience online. A few minutes scrolling on Instagram Reels generates the following six videos:

Taken in isolation, its hard to believe any of these people actually like their romantic partners. Either they’re talking too much or not enough, expressing too much affection or too little, or making themselves just a bit too comfortable in their partner’s life. Am I taking it all too seriously? Maybe. I can see the appeal of these videos. When my boyfriend doesn’t make the bed in the morning, I see red. Like any other couple, we bully each other about stealing the duvets. I leave hair in the sink and he fails to shut the toilet lid. When you spend enough time with another person, you’re more likely to notice their bad habits, and vice versa. A crucial part of having a healthy relationship is knowing how to navigate those bad habits together through understanding and communication.

But we no longer talk about ‘bad habits’, we talk about red flags, and we no longer communicate with individuals, we overshare with, well, everyone. The red flag trend and ‘boyfriend tests’ like orange peel theory or the ketchup challenge (which involves deliberately spilling ketchup to see whether and how your boyfriend cleans it up) occupy the same territory. They express an anxiety within heterosexual relationships — say, a lack of adequate care and attention, or the problem of feminised domestic labour — in a memeified form. They magnify interpersonal tensions as content fodder, looking to capture a ‘gotcha’ moment for the camera, rather than privately and patiently communicating within a given relationship. At the same time, they perform gender dynamics whilst purporting to criticise them, ‘testing’ or ‘exposing’ a given individual rather than making meaningful connections and undertaking in critical reflection which links the personal and political. They display male ‘weaponised incompetence’ in a way that invites the viewer to engage not in structural critique, but individualised displays of anxiety or satisfaction — would my boyfriend clean up the ketchup? Or is he different, special? If he isn’t, I have to dump him. But if he is, if I’ve got a good one, a Lucky Blue to my Nara Smith, do I really need feminism?

By which I mean: the ketchup challenge is not The Feminine Mystique.

Yes, this content makes the private sphere public, so I can see why it may be cathartic for young women, a kind of consciousness raising for the social media age. Yet it engages in neither critical nor emotional work. And it isn’t just progressive women who make this content but men too, as well as women who explicitly reject feminism and perform ‘stay at home girlfriend’ or ‘trad wife’ roles. With their buzzwords and viral trends, they’re a form of exhibition and display, representing an extension of the self-surveillance discussed by Han into a surveillance of our closest intimates. The language of uncovering, detection, and testing suffuses them with a paranoid sensibility, a certainty that the only person who can ever be right is me, the individual, the person who holds the camera, who waves the red, green, or most recently ‘beige’ flag.

Can we really reduce human life down to a series of coloured flags? As well as diluting the original usage of the term ‘red flag’ by domestic abuse survivors, reducing intimacy down to green, beige, and red flags is an exercise in emotional and erotic impoverishment. One article from 2023 calls the beige flag trend a way of starting ‘new conversations’, getting ‘people talking about their partners’ neutral, quirky traits that are neither good, not bad’. But do we really need a new buzzword to talk about our relationships? Is this relentless drive towards categorisation and coordination really the best way to express the messy complexity of human intimacy, to which the mind and body respond in strange and unpredictable ways? Is ‘beige flag’ truly the modern manifestation of the love poetry of Sappho and Rumi, Petrarch and Keats? Or perhaps that’s ‘would you still love me if I was a worm?’.

According to philosopher and critic becca rothfeld, the rise of minimalism and decluttering, which exports the language of corporate efficiency to our private lives, amounts to a stripping back of the intricate, complex tapestry of human life and emotion, which is by definition maximalist and messy.4 Similarly, Han argues that ‘a transparent relationship is a dead one, altogether lacking attraction and vitality’ due to a lack of depth, opacity, and tension, the interplay of concealing and revealing which eroticism is founded on.

The erotic presumes the negativity of the secret and hiddenness. There is no erotics of transparency. Precisely where the secret vanishes in favor of total exhibition and bareness, pornography begins. It is characterised by penetrating, intrusive positivity.5

In Sonnet 130, ‘My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun’, Shakespeare satirises the hyperbolic blazons which defined Elizabethan poetry by comparing his lover’s natural traits to the beauty standards of the day. It all sounds pretty unkind, yet the final couplet of the sonnet reveals that he is not criticising but praising his lover in all her uniqueness. He’d rather have her, with all her flaws, than the rarified beauties who only exist in other poets’ fantasies.

And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare

As any she belied with false compare.

It is her unruliness he loves, her earthliness, her messy hair and ugly voice. She probably ‘yaps’ and gets hangry too, and she certainly wouldn’t have a perfect Instagram feed. But he loves her for, and not despite these things, her strange and secret and imperfect self.

In the digital panopticon, nothing is secret or sacred, just as nothing is dirty or unruly. We are as transparent as products to be bought and sold, shiny and squeaky clean. Even our red flags are carefully ironed. Romance has become a marketplace in which the rich, strange, messy complexity of human intimacy has been boiled down to commodified, optimised traits used to determine value. My algorithm knows I’m in a heterosexual relationship. Pigeonholing me into a particular category — cis woman dating cis man — enables it to make assumptions about the sort of content it thinks I might engage with. Whilst it gets the cute pictures of cats labelled ‘us’ pretty much dead on, the algorithm also believes I must be deeply insecure, distrustful, and looking to ‘test’ my partner for signs of emotional infidelity or red flags. By repeatedly telling me I should feel insecure, this content starts to shape my actual emotional responses within my relationship. Boyfriend test videos in particular are an instruction in insecurity. When you’ve watched enough videos about orange peel theory, your lover suggesting you get your own orange starts to feel like a violation of the commitment you’ve made to each other and an expression of their fundamental unsuitability. You don’t stop to think, would I peel him an orange, if he asked? And why do I want this peeled orange, anyway, rather than a thousand other tiny, far more personal manifestations of love? And why am I reacting in this small-hearted and spiteful way, a way so far from love?

It’s no secret that the algorithmic filter bubbles of the internet fuel confirmation bias and harden pre-existing identities.6 So much of the relationship content I come across takes the form of a joke but plays into age old assumptions about gender — women are needy gossips and men are inattentive slobs, for example. Whilst the odd TikTok poking fun at one’s romantic partner seems innocuous and even feminist-minded, this trend coexists with an insidious rise in bio-essentialist rhetoric, from the disturbing rise in transphobia to the ‘girl phrenology’ propagated by young women (which I wrote about last year) to the popularity of misogynist pick-up artists like Andrew Tate.

Some influencers make whole careers off this kind of content. In one orange peel theory TikTok which went particularly viral, a girl called Shelby stares awkwardly at the camera whilst off screen her boyfriend pontificates about how ‘she’s not that special’ and that he wants to ‘build her up as a female’. Understandably, the response from women online was one of horror. But as Helen Meriel Thomas points out in an article for Vice, Shelby’s account, which now has over 150.6k followers, features endless ‘scripted skits’ where a couple have ‘a suspiciously well-lit albeit toxic argument, in which the camera is always perfectly aligned’. ‘Seeing how my bf would act with another woman’, ‘telling my boyfriend a boring story to see his reaction’, ‘pretending to flirt with a guy on PS5’, and on and on. Shelby is a smart influencer, and she and her boyfriend, who I imagine is complicit in her surely lucrative career of manufactured tension, have hit upon a profitable niche. We love to hate, though this hate always involves an element of comparison with our own lives and relationships, and we’re all voyeurs, eager to peer into each other’s lives.

What this content obscures is that relationships are not simple and digestible in 15 second shorts. Nor are they a transaction, a simple exchange of goods or services, but an ongoing commitment to another human being which requires flexibility, adaptability, and awareness, as well as working through discomfort. But depth and discomfort are anathema to our modern image of relationships, shaped by the language of commodification and propagated on social media. Modern romance claims to be instantly available and constantly accessible, obtained by a swipe on a dating app and maintained via iMessage or Snapchat, and just as easily discarded once it becomes too complicated. In this model, relationships should be easy, self-serving, and endlessly pleasurable by a crude Utilitarian metric. As Han writes, ‘in the course of positivisation, even love flattens out into an arrangement of pleasant feelings and states of arousal without complexity of consequence’, becoming ‘a formula for consumption and comfort. Even the slightest injury must be avoided. Suffering and passion are figures of negativity.’7

What Han formulates as negativity (meaning alterity, drama, darkness, complexity), Rothfield describes as excess, difference, and discomfort. In her essay on sex and the films of David Cronenberg, she argues that good sex is not always simple or predictable, defined by the increasingly narrow concept of consent, which presupposes a prior knowledge of our desires and experiences and which equates ‘good’ with ‘comfortable’.8 Drawing a comparison between sex and body horror, Rothfield instead argues that sex should be a transformative experience, one which brings two people together and makes them anew. Eroticism enters the space of the ‘interhuman…when someone rewrites us so completely that she rewrites even the quality and content of our appetites’.9

Rothfield is concerned here with sex, but is the same not also true of love more broadly; an entanglement with one another so intense that emotions take on physicality and selves make themselves anew, that our appetites remake themselves?10 It doesn’t have to be as extreme as Rothfield’s erotic body horror. Before meeting my boyfriend I would have seen having ice cream for breakfast — in fact, the whole concept of breakfast itself — as something disgusting, bordering on the sinful. And yet that’s what we ate last Monday, overlooking the ocean. Or as Chris Kraus puts it in two passages from Aliens and Anorexia, her experimental text about empathy: ‘emotion is a current that dissolves the boundaries of a person’s subjectivity’ and ‘intersubjectivity occurs at the moment of orgasm’.11 For Kraus, emotion (in Aliens and Anorexia specifically sadness) and sex both remove us from the self and unite us with the Other. We dissolve, and the world reveals itself differently. We are transformed.

I love Rothfield’s formulation of sexual encounters as ‘interhuman’, though I think it is utopian. How can we ever hope to undergo this kind of no-holds-barred transformation when we’re halted by all those red flags planted firmly in the no-man’s land of desire? In selling romance, social media flattens it. Transformation is not soundtracked by a trending TikTok audio, nor is it ‘suspiciously well lit’, nor living in fear that screenshots of its sexts will be tweeted for a laugh.

What do we seek to gain from this type of relationship content? In The Transparency Society, Han argues that whilst transparency is assumed to be a prerequisite of trust, it actually has an adverse affect, and ‘strident calls for transparency point to the simple fact that the moral foundation of society has grown faulty’, with values such as honesty crumbling under neoliberal pressure.12 I’m unsure about this thesis as Han applies it to political trust — without an element of transparency, how could we meaningfully interrogate the private, or for that matter the public sphere, with its gender pay gap and discriminatory hiring practices? — but applying it to interpersonal relationships is thought-provoking. We want to trust the people we chose to share our lives with. Red flag trends, boyfriend tests, and relationship content more generally assumes that we can obtain trust through transparency, by scrutinising and documenting, by vetting our lover’s Instagram feed for bikini-clad models and diagramming exactly how poorly they share the duvet. We trust in so-called relationship gurus, pick-up artists, and random influencers online, rather than those we are most intimate with in the real world, a 20 second TikTok from a stranger over the natural processes of growing together and apart than may take place over years. Setting aside obvious and extreme examples of breached trust such as cheating, is this constant interrogation really the recipe for a healthy, trusting, even transformative relationship?

We can never truly know another person in their entirety, and if we did, could we really love and desire them? The digital panopticon tells us we must know everything, see everything, compare everything in our own lives and others. It promises us trust but fosters insecurity, jealousy, avarice, a vision of love as a commodity we can buy into and discard when it no longer serves us. A vision of love so shallow and surface-level is one I want to no part in yet cannot help but be seduced by. Seduced not as a lover but as a consumer, by bright glossy promises and carefully-lit TikToks and endless trends and hacks and buzzwords which promise to shine their fluorescent lights on the dimly lit spaces of love.

There is nothing erotic, romantic, emotional, or sensual about dating in the digital panopticon. There is no shadowed twilight, no place to hide away and reflect, no place to fall in love. And all the oranges are peeled, stripped of their pith, dried out and unappetising and fleshless in the glaring midday sun, which beats down upon us like a hungry, desperate eye.

Twenty-first century demoniac is a reader-supported publication. You can subscribe now for free or for the small price of £3.50 monthly. That’s (sadly) less than a coffee, and probably about the same as a bag of oranges. I promise I’ll share them with my boyfriend.

For posterity, my boyfriend, and the fact checkers, he did not say this. I said this. I am putting words in his mouth, because unfortunately for him that is what happens when you date a narcissist / writer. What he said was ‘no’.

Byung-Chul Han, The Transparency Society, p. 49

Han, The Transparency Society, p. viii

Becca Rothfield, ‘More is More’ in All Things are Too Small (2024), p. 13

Han, The Transparency Society, p. 4, 25

See, for example Eli Pariser, The Filter Bubble: What the internet is hiding from you (2012)

Han, The Transparency Society, p. 5-6

Rothfield, ‘The Flesh, It Makes You Crazy’ in All Things are Too Small, p. 78. Also available online.

Rothfield, ‘The Flesh, It Makes You Crazy’, p. 76

In an entirely unrelated anecdote, my boyfriend and I have been asked twice this month if we always coordinate our outfits. We never do! Ever!

Chris Kraus, Aliens and Anorexia (2000), p. 95, p.160

Han, The Transparency Society, p. 48

Literally like 🤯🤯...the bit about the erotic being inter- human is DELICIOUS

I was reading this and nodding along like "yeah, that do be how it is" all normal-like, and then I got to that Rothfield citation, for the Cronenberg essay, and now I have to take time out to figure out how to bypass the New Yorker's paywall so that I can read the original, because omg. What a fascinating recommendation, thank you!!