the oxford effect

thinking about dark academia, old money aesthetics, and the 'elite' university in the wake of saltburn

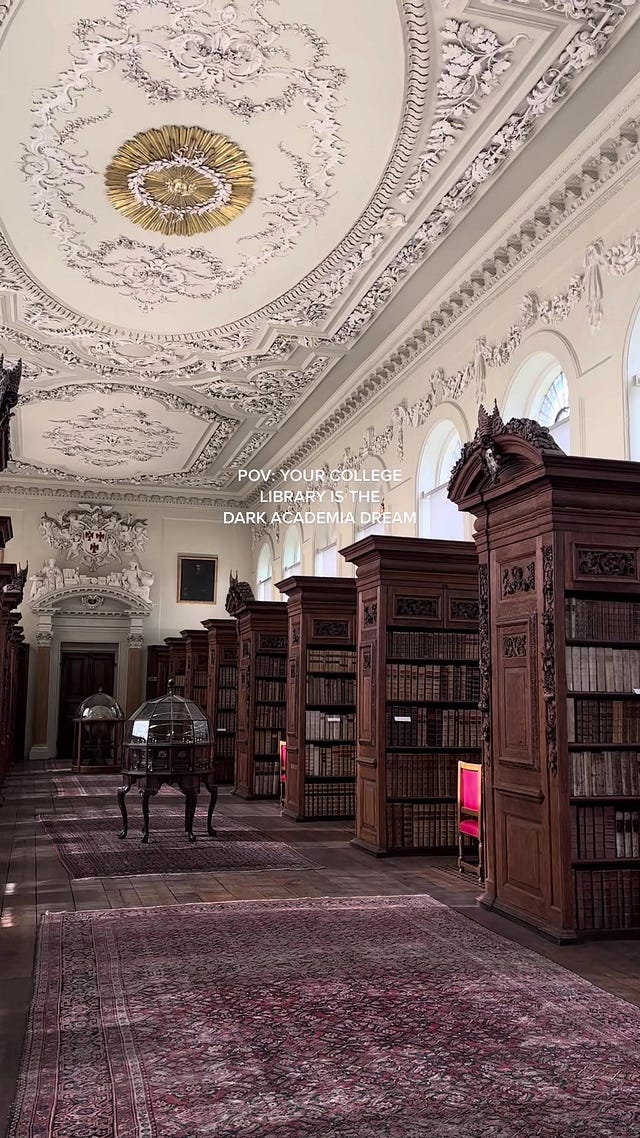

I turned up to Oxford University in 2019 with a brain full of misconceptions and a suitcase stuffed with beige cable knit sweaters and H&M tweed. I’d been conditioned by Tumblr compilations of lacy shirts and herringbone coats, Pinterest boards full of Greek statues and women running through art galleries, and a literary diet which was heavy on the Donna Tartt. I refused to wear colour, and privately disdained the idea of going out when I could be studying. My idea of Oxford was all grand halls and eighteenth-century libraries, and I was fully expecting to form a homosocial bond with an eccentric academic. It was the dawn of dark academia and Oxford was the perfect place to indulge.

Oxford is a university, an educational institution and a centre for research, but it is also an idea and an image shaped by centuries of history and culture. This imagined Oxford holds a near-unbroken sway over the British imagination. It is ivory towers and dreaming spires. It is Prosecco and punting and sub fusc and badly behaved boys in black tie. It is a place for the most intelligent people in the country, and the most morally dubious. It is somehow both an arch-conservative stronghold and a hotbed of radical ideas. It is possibly still stuck in the 1700s. It has remained constantly relevant since its founding nearly 1000 years ago. It is always in the press, on our TV screens, on the pages of our novels; no other university in the UK or even the world has generated quite so much opinion, quite so much literature, so much art.

‘No one ever really leaves Oxford’, someone told me, shortly after my graduation and before I returned for my Masters. ‘You carry it with you; you will always be looking back.’ The filmmaker Emerald Fennell would probably agree. The first half of her controversial sophomore hit Saltburn is a self-indulgent montage of rich kids and their less consequential classmates at Oxford circa 2006, about the same time Fennell (herself the scion of aristocrats) attended the university. The second half is a messy psychosexual romp set on leaving the viewer as discomforted as possible, whilst the final five minutes drain what remains of the plot away into incoherence like dirty bathwater. Suffice to say, in the great debate over whether Saltburn was ‘stupid in a good way or a bad way’, I fall firmly in the latter camp.1 Billed as Brideshead Revisited meets The Talented Mr Ripley, the film manages to live up to neither. What it has done is put Oxford and it’s traditions firmly back in the cultural limelight and launch a series of discussions about class, wealth, and nepotism, all issues firmly bound up with the university’s reputation as an old boy’s club for the British elite.

Saltburn is the latest in a long line of films, TV shows, and novels to draw on Oxford’s pervasive allure — that we love to hate it, that we can’t quite get away. You’re never more aware of this media over-saturation than when you wander through the city itself, passing twee shops selling Harry Potter merchandise and tour guides gesticulating wildly about the Inklings or noting the gap where fictitious colleges made famous by Endeavour and His Dark Materials might have stood. I frequently found my commute delayed by film sets, for Wonka, Saltburn, The Crown, and A Discovery of Witches to name just a few. The first time I saw the city was on a school trip, where we recreated famous shots from The History Boys — at least it wasn’t The Riot Club, the 2014 thriller inspired by the infamous Bullingdon Club of David Cameron-doing-revolting-things-with-a-pig fame. But it is on the internet where Oxford has found a new cultural status, as part of the dark academia aesthetic and its various offshoots.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

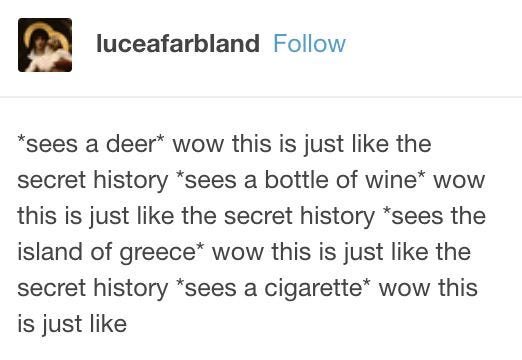

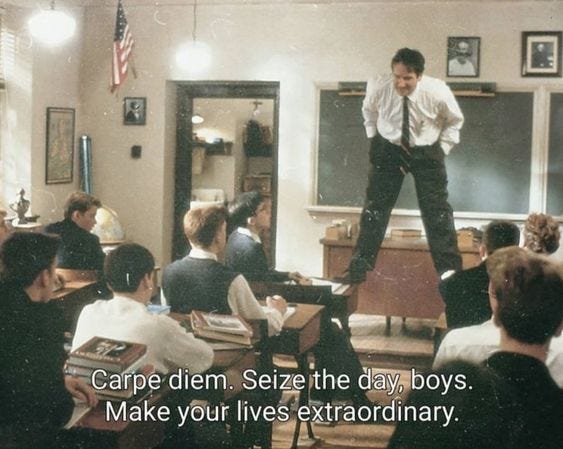

Defined by Aesthetics Wiki as an ‘aesthetic that revolves around classic literature, the pursuit of self-discovery, and a general passion for knowledge and learning’ with ‘an allure that presents schooling as not dreary or boring, but one that cultivates mystery, curiosity, and diligence that isn't commonly seen in contemporary schooling’, dark academia emerged in 2017 and spread across Tumblr and Pinterest, where I encountered it. On these platforms, dark academia was pioneered by fans of Donna Tartt’s 1993 novel The Secret History, which follows the unravelling of a close-knit group of Classics students at an elite New England arts college. Often listed alongside more recent novels, many of which fell into the YA genre (such as The Raven Boys, If We Were Villains, and Ninth House), and popular movies like Kill Your Darlings and Dead Poets Society, The Secret History played a profound influence on early dark academia with its depiction of intense intellectual companionship, compelling imagery of wealth and prestige, and shadowy air of intrigue.

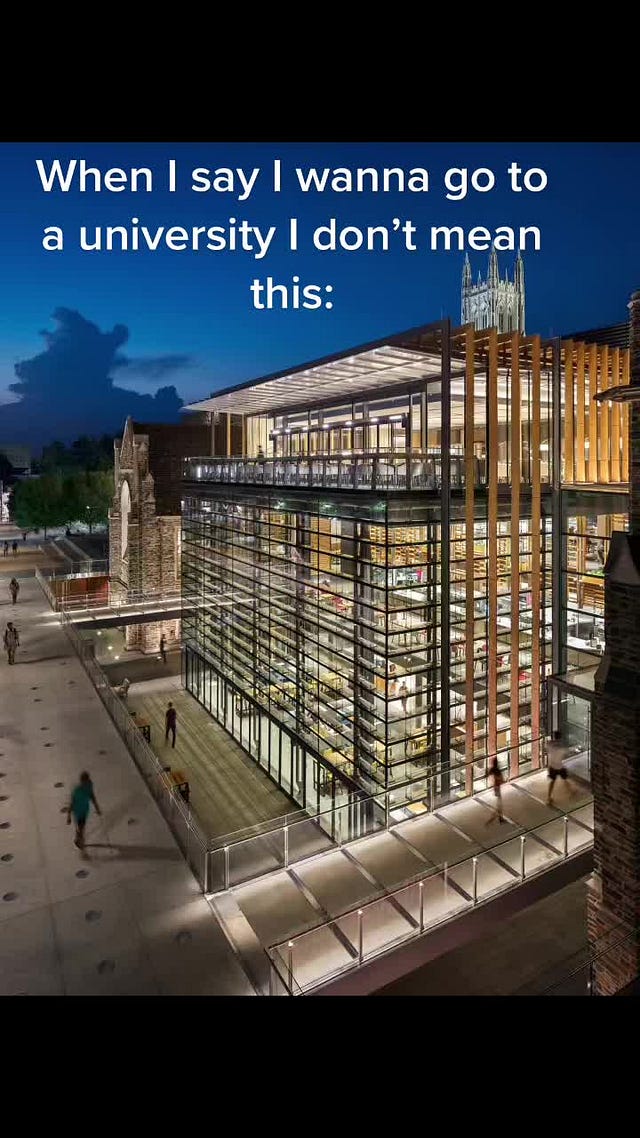

But it was in 2020 as lockdown disrupted in-person teaching at schools and universities that dark academia exploded into the mainstream, finding a new home on TikTok. Whilst still influenced by film and literature, dark academia grew increasingly fashion-focussed on TikTok’s image-oriented platform, embracing traditionally ‘autumnal and bookish’ outfits and depicting studying as something stylish, rather than uncool or frumpy.2 As both a literary genre descended from the campus novel and a visual aesthetic, dark academia is deeply influenced by the idea of the university, particularly a historic and renowned institution such as Oxford; it’s ‘the dream of studying at a prestigious Anglo-Saxon university – but not so much a contemporary one, but rather one from a few decades ago’.3 Think tweed jackets and wire-rimmed glasses, leather-bound books used as coasters for crystal glasses of whiskey or red wine, libraries filled with classical statues and elegant students, and deep conversation in Latin or Greek emerging from a fog of cigarette smoke and frost. This is a vision of academia defined by mystery, romantic allure, and eccentric erudition, one which holds an intoxicating power.

Saltburn begins at Oxford but it isn’t quite a dark academia film — neither Oliver nor Felix seems to care much for studying. It aligns far better with another fad of the 2020s, the obsession with wealth, luxury, and status encapsulated by the old money, quiet luxury, and rich kid lifestyle aesthetics which have proliferated alongside dark academia — though the two aren’t that separate. Historically and in today’s media, Oxford sits at this conjunction between wealth and academia. Indeed, many of the signifiers of dark academia are also signifiers of wealth; think opulent bookshelves and expensive but understated outfits. Oxbridge and the Ivies feature in both aesthetics as a marker of status as well as intellect, as they do more broadly in popular culture. It is only in my lifetime that university education has become a universal ideal, at least in the UK; go back to the 1930s-50s, the inspiration for dark academia’s retro style, and the idea of a diverse, inclusive university was still a remote fantasy.

This exclusivity is encapsulated by the popularity of the Ivy League style, the casual, sporty yet tailored menswear which evolved on elite American campuses in the mid-twentieth century and which saw a popular revival in the 90s and noughties as the preppy look with brands like Ralph Lauren, J Crew, and Abercrombie bringing button down shirts, blazers, and tweed to suburban malls.4 Ivy style, like the British country style seen on the Royal Family and the pages of Tatler, belonged to an explicitly upper class subculture, as an unspoken way of positioning oneself in relation to this Anglo-American elite in-group defined by wealth and education. The return of this style in conjunction with nostalgia for both the noughties and pre-war fashion eras has influenced both dark academia and old money ‘cores’, aesthetics which enable consumers to mimic and flaunt the trappings of a lifestyle without necessarily having access to it. Saltburn is just the latest piece of media to reaffirm the connections between academia and wealth and to unite the two through the display of grandeur and opulence which consumers desire to emulate despite its unattainability — as critics have said, what it lacks for in plot, it makes up for in ‘vibes’.5

Dark academia isn’t just about studying, it’s about studying as an expression of beauty, and a condescension verging on snobbery towards those who don’t live up to this ideal. In coupling beauty and intelligence, it reinforces a Western, Eurocentric vision of both whilst indulging in imagery which perpetuates the idea of academia as a playground for the wealthy, much as Saltburn does. In doing so, it legitimises the very real hierarchies, stereotypes, and prejudices which many scholars today are working tirelessly to overthrow. A quick search for ‘dark academia’ on TikTok yields thousands of results predominantly depicting white, slim, able-bodied, and conventionally attractive men and women in settings such as libraries, lush quads, and class. Neither the people nor the topics labelled as ‘academic’ are diverse, sticking firmly within a Eurocentric vision of culture. An average dark academia moodboard pays homage to the traditional Western canon with Pre-Raphelite art, a leather-bound Penguin classic, and Greco-Roman statues. As this suggests, the focus of dark academia is on the past, ostensibly as a topic of study but more often as a subject for veneration and idealisation as a time of splendour and nobility lost to modernity — a deeply conservative impulse. Alongside these moodboards and the ubiquitous tutorials for ‘dressing dark academia’ or ‘dark academia hobbies’ are even more dubious videos, including ‘dark academia old money restaurant recommendations’, and ‘choose your path at an elite boarding school’.6 As numerous institutions, Oxford included, uncouple from wealthy donors such as the Sackler family over their connections with the drugs and arms trades, can we really not imagine an aspirational academia free from from ‘elite’ or ‘old money’ networks and the violence they have inflicted?7

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

When dark academia is done well it can attack those hierarchies and the allure that surrounds them — I’m thinking here of R.F Kuang’s harrowing 2022 epic Babel which positions Oxford at the heart of a fantastical British Empire powered by language itself. Babel’s Chinese-born protagonist, Robin Swift, is initially drawn into the romance of Oxford despite knowing he is there on imperial sufferance to enact the translation work which powers the magical force of empire.

They were men at Oxford; they were not Oxford men. But the enormity of this knowledge was so devastating, such a vicious antithesis to the three golden days they’d blindly enjoyed, that neither of them could say it out loud.8

It is when Swift falls out of love with the ‘golden days’ of Oxford, coming face to face with the violence seething below the serene surface of academic dinners and late night library sessions, that the book becomes a vital piece of social criticism which has as much to say about the fantasy of Oxford itself as it does about empire, colonialism, and racism in Britain. The aesthetics of elite academia, Kuang seems to suggest, provide a prettified cover up for its dirty realities, the bad as well as the good. It’s easy to fall uncritically for this ‘Oxford effect’, especially if you come from a more privileged background.

The ‘let people enjoy things’ crowd are breathing down my neck. ‘Its just vibes! Its just an aesthetic! Its just fashion!’. I don’t need to quote the Devil Wears Prada cerulean sweater speech to know that fashion is never just fashion. It reveals assumptions about value and worth, about in-groups and out-groups. Moreover, the way in which one presents oneself, particularly through clothing, has a profound influence on others’ perception of one’s intelligence and competence, especially for people of colour and women. I remember hearing an established female academic speak about the prejudice she faced for dressing or not dressing in a certain way — too feminine, too sexy, too loud, too much makeup. It is a commonplace that women are defined by their bodies, men by their minds, and this plays out in everyday clothing choices. A 1991 study, for example, demonstrated that both teachers and students were influenced in their perceptions of students’ scholastic potential by dress and gender.9 To draw attention to the feminised body is to draw attention away from one’s intellect, the mind and its capacities which are prized in academia.

As with most online subcultures, women are the predominant creators and consumers of dark academia content, which we could see as a way to reject the male/female, mind/body dichotomy and reassert female intelligence. In many of the movies and novels labelled ‘dark academia’, women are self-effacing shadows of the intelligent, brilliant men who take centre stage. Much of this has to do with the period setting of many of these dramas (think Theory of Everything, or the History Boys, or more recently Oppenheimer), their homoerotic subtext (Kill Your Darlings, The Talented Mr Ripley) and their use of the all-boys school as a stand-in for the elite university (Dead Poets Society). But it also has to do with the way women have historically been treated in scholarship. They are helpers, carers, secretaries. They do not have ideas, they take notes. Even in The Secret History, the most infamous and perhaps the first dark academia novel, Camilla exists in part to heighten Tartt’s depiction of masculine brotherhood, and is as androgynous as she is feminised. She is a sexual object but also a kind of honorary boy.

So in a way dark academia fashion, predominantly consumed by women, has a revisionary potential. To dress in the garb of traditional academia is to assert your space within that tradition, to deny and defy women’s traditional absence from the academic institution. Every day at Oxford I stepped over a plaque commemorating the first female students to enter my college, in 1974. To do so dressed like a 1930s don could look like a radical act. On the flip-side, to feminise the male protagonists of dark academia (think Robert J. Oppenheimer as ‘baby girl’ or Henry Winter as a ‘soft boi’) emphasises the value of feminine characteristics to genius, even if that genius involves, uh, weapons-manufacture or cold-blooded murder.10 But this reclaiming only goes so far.

Academia, especially at Oxbridge, has long been an old boys club, the prestige of wealthy men. Dark academia’s fascination with that prestige is the source of its sartorial allure, and its moral failing. As with the old money trend, it’s a case of if you can’t beat them, join them. And if you can’t join them, at least try and look like you can.

In the case of the old money aesthetic, that emulation reestablishes the cultural supremacy of the super-wealthy, enabling scions of the aristocracy like Fennell to flaunt their wealth and connections, on the red carpet or on TikTok. Just look at the trend of super wealthy teenagers parading around their family piles to a soundtrack of Sophie Ellis-Bextor, evidently missing whatever point Saltburn might have managed to make.11 It feels like a backlash against the decades since the 1960s, when fashion began to be set by subcultures from outside the upper classes, such as hippie, punk, and grunge, with radical political associations. With the rise of social media, the internet’s micro-trends, cores, and aesthetics have moved us away from the traditional definition of subcultural style as ‘the expressive forms and rituals of those subordinate groups...who are alternately dismissed, denounced and canonized’,12 a symbolic form of resistance by a cultural minority, to a purely visual community, enabling a single aesthetic to encompass both the hollow posturing of super-wealthy teenagers and their less well off counterparts in Shop Cider blazers and shirts. But the association is just as insidious when it comes to the academia aesthetic, perpetuating and romanticising a traditional image of learning bound up with upper class networks and values, traditionalism and conservative nostalgia for the past, rather than thinking critically about what learning is, who has been excluded from it, and how it can be reevaluated and expanded today. Rather than posing a ‘challenge to hegemony…expressed obliquely, in style’, these aesthetics confirm its ideological status.13

This nostalgic yearning for an imagined past is a conservative tendency, and one which has gained a disturbing prominence online in recent years — the rise of the trad wife being perhaps the most notable. A cultural narrow-mindedness has penetrated the mainstream of online discourse, with the last few weeks seeing a debate over the value of modern art go viral, labelling works by modern masters like Mark Rothko as ugly, pointless, and easily replicable by amateurs. Meanwhile @The Cultural Tutor, a Twitter account with over 1.6 million followers and many copycats, claims to champion ‘Western culture and civilisation’ through short posts on history, literature, philosophy and art; owner Sheehan Quirke also writes for right-wing British publication The Critic.14 Much like dark academia accounts, Quirke promises his followers ‘A Beautiful Education’, narrowly defined.15 @Culture_Crit, a similar account with one million followers, shades even closer to fascism, claiming ‘Tradition is not the worship of ashes, but the preservation of fire’.16 Their shared definition of learning as the preservation of a glorious past holds little space for the diverse messiness of modern life.

This desire for education to be beautiful is the same issue that plagues fans of The Secret History — ironically much like the character of Richard Papen himself, whose blind veneration of a lifestyle without deeper consideration leads him to a place of pain for both himself and others. Like Robin Swift at the start of Babel, Richard is seduced by an alluring group of students by the promise of community and status they provide. It is not intelligence that draws Richard in, but the beauty associated with it.

Does such a thing as 'the fatal flaw,' that showy dark crack running down the middle of a life, exist outside of literature? I used to think it didn't. Now I think it does. And I think that mine is this: a morbid longing for the picturesque at all costs.17

Dark academia fans share that ‘morbid longing for the picturesque at all costs’.

In emphasising the ‘picturesque’ or ‘aesthetic’, the dark academia lifestyle has become one of consumption, not engagement, a contrived signalling of one’s individual erudition whilst actually following trends. And this is the aesthetic’s ‘fatal flaw’. If we only read what is beautiful, only purchase books with beautiful covers and classical pedigree, we risk neglecting a diverse range of history and literature by female, queer. non-white, and non-Western authors. If our only engagement with history is to venerate the past as a lost time of grandeur, we fall into a conservative view of modernity and progress, and fail to appreciate the historiographical position which urges us to assess history on its own terms. If we only admire conventionally ‘beautiful’ art, we fail to appreciate the power and politics of modern art, even as it challenges us with its plain or ‘ugly’ demeanour. And if we fetishise academia as a ‘beautiful education’, we will inevitably be disappointed.

It is a curious fact that interest in the aesthetics of academia has increased in an era when academia itself is being so systematically devalued. We are living through an unprecedented attack on the university system, on the value of the humanities and the ideals of learning. In the UK, Rishi Sunak announces a ‘crackdown’ on ‘rip-off’ university degrees and urge the promotion of STEM subjects, whilst the national press ‘cheer decline of humanities degrees’.18 Universities remain a battleground in the conservative ‘war on woke’, an American import against the teaching of feminist, gender, and critical race studies and progressive revisions to curricula, as well as the de-platforming of academics accused of harassment or discrimination. This somewhat contradictory weaponising of free speech has been fully embraced by the British right, in tandem with the lampooning of academia as a bastion of ‘elite’ (liberal) and ‘exclusive’ (peer-reviewed) ideals. Meanwhile, the very real issues impacting the academic discipline — such as sharp cuts to staff pay and gender discrimination — fly under the radar, with the 2018-23 UCU strikes used to divide staff and students on the grounds of ‘value for money’. According to the Education Secretary, ‘Students and taxpayers rightly expect value for money and a good return on the significant financial investment they make in higher education.’ Yes, students who are paying high tuition fees at considerable financial risk should receive what they pay for, but the creeping corporatisation acts to conceal the manifold issues facing the system and sets up education as yet another consumer good — is investing in an education really no different to investing in a wardrobe?19

Higher education in the UK is being hollowed out, stripped of its ideals and corporatised for a student-body who are increasingly labelled as consumers rather than active participants in an intellectual exchange. Against this backdrop, what does the academia aesthetic signify? I don’t think its a coincidence that dark academia and its offshoots emerged in the late 2010s, in conjunction with (in the UK) falling student satisfaction, increasingly dire conditions for university staff culminating in the UCU strikes, and the accelerating ‘culture wars’ around education.20 Nor is it unexpected that 2020 saw it hit the mainstream, when schools and universities were precariously positioned during lockdown. As late capitalism tightened its grip and tertiary education became a product, a service, a consumer good, an investment, rather than a means of expanding one’s horizons and extending one’s knowledge, nostalgia kicked in. Such nostalgia is tightly bound up with the internet’s aesthetic culture — think of Y2K style, or the indie sleaze revival, or even Saltburn’s nonspecific 2006. Faced with online learning, bland administrative offices, commodified brand deals and daunting fresher’s weeks, SFE emails and 200+ seat lecture halls, dark academia offers a vision of academia which is rich with beauty and wonder, which promises mystery and discovery, which is seeped in a long history and literary tradition. An academia which meanders the candle-lit corridors of wood-panelled libraries and strides in a wool overcoat through wintery streets. It offers, in other words, a vision of academia which does not really exist in the twenty-first century — even at Oxford, its lodestar.

There’s a purely escapist impulse to such romanticisation, but is this aestheticising impulse conducive to good learning? Do the expectations it creates enable productive pedagogy, or hinder it? Is it that far from the late capitalist impulse which is systematically gutting our higher education systems for corporate profit and government rhetoric?

There’s something hollow about an interest in literature, history, art, and so on merely as a marker of online identity and visual style. This emphasis on the aesthetic above all else benefits the fast fashion brands and algorithm-driven tech giants of today whilst reproducing the status-markers of the past. And the overlap with the aesthetics of opulence demonstrates the undemocratic impulse behind dark academia, its internalised snobbery and self-conscious projection of surface intelligence at the expense of deep, diverse critical thinking. The misguided obsession with the desperate, dangerous characters of The Secret History as role models for a whole lifestyle is perhaps the clearest example; that ‘morbid longing for the picturesque’ which Tartt shows to be fatal. There is no way to live the ‘dark academia lifestyle’, no matter where you go to university. Oxford University may have wealth, history, and resources, but it is ultimately just another university. To focus solely on its romantic aspects — whether thats grand libraries or boozy seminars — is to paper over the cracks in the facade, to ignore the many flaws with the institution and the ways in which real people are trying to reform it. To focus on the beauty of the past — as The Cultural Tutor does, with his promise of ‘A Beautiful Education’ — is to ignore its ugliness, its raw humanity. Maybe dark academia will encourage more people to read the classics or learn a language or explore history and art. But doing these things for the ‘aesthetic’ is a surface level performance which is about as transformative as putting on some wire-rimmed fake glasses.

What an Oxford education — what any education — should provide you with is critical insight, analytical skill, and an expanded imagination. Education of this kind cares about the past and the future, not just for their value to the present economic or political situation or for the image they help project, though these may be of interest, but for the fact that human life is interesting and intrinsically worthy of fascination. Scholarship does not always look intelligent, nor does it always feel valuable. Sometimes it is a dull slog. Often it eats its own tail in debates about its methodologies, its theory, its purposes. Mostly it is destined for footnotes. But it is always worth pursuing, regardless of the graduate salary it may generate or the social status it conveys.

Not unlike ‘culture and civilisation’ style accounts with their fascistic veneration of cold marble and stone, the academia aesthetic worships at the altar of academia without knowledge of its scripture. It obsesses, emulates, copies. It is a crude imitation of a bygone past and yet it constantly champions its own intelligence. Each choice signals its erudition, from the tweed jacket to the leather-bound classics to the Greek statuette. It is contrived, with an artificial affectation that is the death of good scholarship. It positions itself aesthetically within traditional hierarchies and stereotypes and in doing so reasserts rather than dismantling them. It, like the corporatised university, is something to be sold, a promise you buy into, a status symbol you flaunt online. It is beautiful and so it is alluring but it is hollow and opposed to the messy, precarious reality of academic life. It is beautiful, but to let the Bible of dark academia itself have the final word: such beauty is terror.

Thank you to everyone for the love on last month’s girlhood essay. Twenty-first century demoniac is my passion project and it’s incredible to find my words resonating. I also appreciate every like, comment, and subscription, especially paid subscriptions. For less than the price of a monthly oat latte, you can support my work and ensure many more lengthy essays filled with dark academia-esque pretensions land in your inbox.

R. F. Kuang, Babel: Or the Necessity of Violence: An Arcane History of the Oxford Translators' Revolution (2022)

Behling, D. U., & Williams, E. A. (1991). Influence of Dress on Perception of Intelligence and Expectations of Scholastic Achievement. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 9(4), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887302X9100900401

More on babygirlification in last month’s essay, on the girlhood trend:

Dick Hebdidge, Subculture: The meaning of style (1979)

Ibid.

Donna Tartt, The Secret History (1992)

This article is really good on some of the issues facing UK unis today https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v45/n13/fraser-macdonald/short-cuts