dispossessing pathological femininity

sex, sickness, and the devil in the seventeenth century

TW: discussion of sexual assault, rape, disordered eating in a historical context.

In the infamous Denham exorcisms of the 1580s, 15 year old servant Sara Williams and her older sister Friswood were forcefully dispossessed by a group of Jesuit priests residing with their employers. Shortly after joining the Denham household, Williams had fallen unwell. She believed herself to be suffering from suffocation of the mother, a uterine disorder considered by historians as the forerunner of hysteria. The exorcists disagreed.

Sara and Friswood were isolated from friends and family, forced to convert, and underwent emotionally and physically intense public exorcisms to rid them of their demons. In Sara’s case, the exorcists located the demon’s evil influence in her genitals, especially during menstruation. In her witness statement she describes how the priests ‘deuised to apply the reliques vnto it, and gaue her…sliber-sawces.’ Fluid was ‘squirt[ed]...by her priuie parts into her body, which made her very sick....She sustained very great hurt’. When the devil finally ‘departed out of her by her priuiest part…[it] had torne those parts’.1 Curing the body through purgation was not unusual in the early modern era, yet in the Denham exorcisms this ‘cure’ took the form of forced and aggressive masturbation.

The case of Sara Williams is a dark one, and one which requires a degree of critical distance (Willliams and the main chroniclers of the case were Protestants and the Denham household firmly Catholic in an age of intense religious division). Yet it is not unusual. In the seventeenth century sex, sickness, and the devil were tightly bound together in a nexus of power and violence. In Shakespeare and Fletcher’s Two Noble Kinsmen, first performed in the early 1610s, a time when the spectre of Denham was haunting public discourse thanks to the infamous possession cases of Mary Glover (1602) and Anne Gunter (1605), another sick young woman finds herself ‘cured’ through the sexual intervention of a group of men.

Lacking even a name, the Jailer’s Daughter is defined solely by her relationships to men — her father, physicians, lovers. At first an eloquent young woman, her unrequited love for the imprisoned Palamon sends her into mad ramblings, erotic advances, and suicidal impulses. In her father’s words:

‘She is continually in a harmless distemper: sleeps little; altogether without appetite, save often drinking; dreaming of another world, and a better; and what broken piece of matter soe'er she's about, the name 'Palamon' lards it, that she farces every business.’

As she dances deranged through the forest, the Daughter calls out ‘for a prick now’, much like the maid in a contemporaneous ballad pining away ‘for want of a dildoul’. To the men she begs ‘company’ from she is both fey and strange, a ‘dainty madwoman’ who becomes an object of both sexual and farcical potential as they goad her to dance, opining that ‘she'll do the rarest gambols’. Unlike Ophelia, her upper class, lovesick counterpart in Hamlet, the Jailer’s Daughter is rescued from madness and drowning by a suitor who is, in the world of the play and of the seventeenth century more broadly, not just sexual partner but medical cure. Questioned by her desperate father, a doctor has prescribed the substitution of a ‘fake’ Palamon for the object of the Daughter’s affections and the source of her ‘perturbed mind’. A fake wooer will enable the copulation necessary to cure the Daughter’s disease. ‘Do anything’, the doctor advises. ‘Lie with her if she ask you…in the way of cure.’2

To the modern mind, the idea that sex might provide the cure for sickness is strange, disturbing, and tinged with rapey overtones. Yet for many years sex was an accepted and common therapy for young women suffering from ‘greensickness’, also known as the disease of virgins. Emerging in 1550s England yet acknowledged until the late nineteenth century, the disease of virgins has been characterised as ‘a historical condition involving lack of menstruation, dietary disturbances, altered skin colour and general weakness once thought to affect, almost exclusively, young girls at puberty.’3 As its popular name implies, the disease’s cure involved ending the girl’s virginal state through marriage, intercourse, and pregnancy. As the popular gynaecologist Nicholas Culpeper explained:

‘It is probable, and agreeable to reason and experience that Venery is good [for greensickness]. Hippocrates bids them presently marry, for if they conceive they are cured. John Langius saith this disease comes in the ripeness of age or presently after. Venery heats the womb and the parts adjacent, opens and loosens the passages, so that the terms may better flow to the womb.’4

The Jailer’s Daughter’s condition is clearly coded as greensickness, tied to her age, menstrual problems, and unruly desire for Palamon. Similarly, the demoniac Sara Williams’s self-diagnosis of suffocation of the mother was unusual for the time; she was far more likely to be diagnosed with greensickness due to her age and unmarried status. Yet the distinctions between women’s uterine disorders were not firmly bounded, and both greensickness and suffocation of the mother had as their cause the innate weakness of female minds and bodies.

At the end of The Two Noble Kinsmen, the Jailer’s Daughter and her unruly mouth(s?) slips silently offstage, the victim of a conspiracy of men and medicine against women’s madness. Greensickness and possession sit side by side as disorders of pubescent girls which can and must be cured by male control. Father, physician, exorcist, lover, rapist, judge — it is their epistemological authority which defines the status of the mad/sick/possessed girl, even as her body defies their gaze and elides easy categorisation. Early modern gynaecology and midwifery has been depicted as concerned with 'the politics of knowledge’, with the anatomisation and categorisation of the female body.5 Yet that body was never stable; pica, the eating disorder on which I am writing my dissertation, was both a symptom of greensickness and pregnancy, contesting the strict boundary between virginity and (illicit) pregnancy. In a 1632 play by Ben Johnson, The Magnetic Lady, the fake heiress Placentia’s pica cravings for ‘lime, and hair, Soap-ashes, loam’ are assumed to be greensickness, but actually reveal an illicit pregnancy.6 The physicians and suitors who diagnose her with ‘a dainty spice O’the green sickness’ both exercise male control through diagnostic knowledge and assume that knowledge to be authoritative due to its scientific rationality. Greensickness as a diagnostic tool serves two ends — it ascribes patriarchal meaning to the impenetrable insides of the female body whilst signifying its physical readiness to be penetrated. Yet inherent within it is the fear of female duplicity.

Femininity is always pathologised under patriarchy, writes Helen Malson in The Thin Woman; ‘as the Other of ‘rational man’, ’woman’ has often been ‘fictioned’ as sick, intellectually impaired and as irrational and mad’.7 The Jailer’s Daughter’s greensickness and Placentia’s pregnancy cravings are simply the extreme yet inevitable endpoint of female biology, the excessive flux and fluids of the early modern humoural body, the irrationality of woman first manifest in Eve at the Fall and passed, through the transfiguration of menstrual blood into mother’s milk, through the generations. At fourteen or fifteen, wrote the anonymous author of Aristotle’s Masterpiece in 1684, women’s ‘Menses, or Natural Purgations begin to flow: And the Blood, which is no longer taken to augment their Bodies, a∣bounding, incites their Minds and Imaginations to Venery.’8 Femininity manifests the fallen, fleshly state of humanity and continually threatens the stability of the patriarchal system through excessive ‘venery’. The Masterpiece continues: ‘the Body becomes still more and more heated, than the irration and proneness to Veneral Embroces, is very great, nay, sometimes al∣most insuparable. And a due use of these Enjoyments being deny'd to Virgins, very often produces very dismal Effects’. Femininity is sexuality and sexuality unsatisfied through the legitimate institution of marriage is pathology.

Jonathan Sawday characterises the rise of anatomical science in the seventeenth century as a male science which observed and a female subject who was observed, suggesting that ‘the encounter was not one determined simply by an active male gaze confronting a passive female subject. The exchange, in the Renaissance, was at once more complex, and more overt’, a conflict and triumph over the dangers inherent within the male-imagined female body.9 The early moderns feared women, they needed to possess them. Religious and local conflicts determined the 1603 trial disputing the possession by the devil of teenager Mary Glover. Some authorities saw her as a faker, others a legitimately sick child, others blamed familial and confessional influences for manipulating her. One, the physician Edward Jorden, labelled her condition as hysteria, whilst cleric Samuel Harsnett drew on the Denham exorcisms and Sara Williams’s confession to argue for fakery. In the later case of Anne Gunter Jorden again consulted, though Gunter’s domineering father was found to be the true agent in her possession, encouraging her symptoms including by feeding her emetics. These trials showed intense anxiety about the potential that demoniacs were engaged in fraud, much like their pregnant ‘greensick’ sisters. Possession by a male authority, be it the devil or a conspiring father, was far more legitimate than the female agency implied in an active fraud.

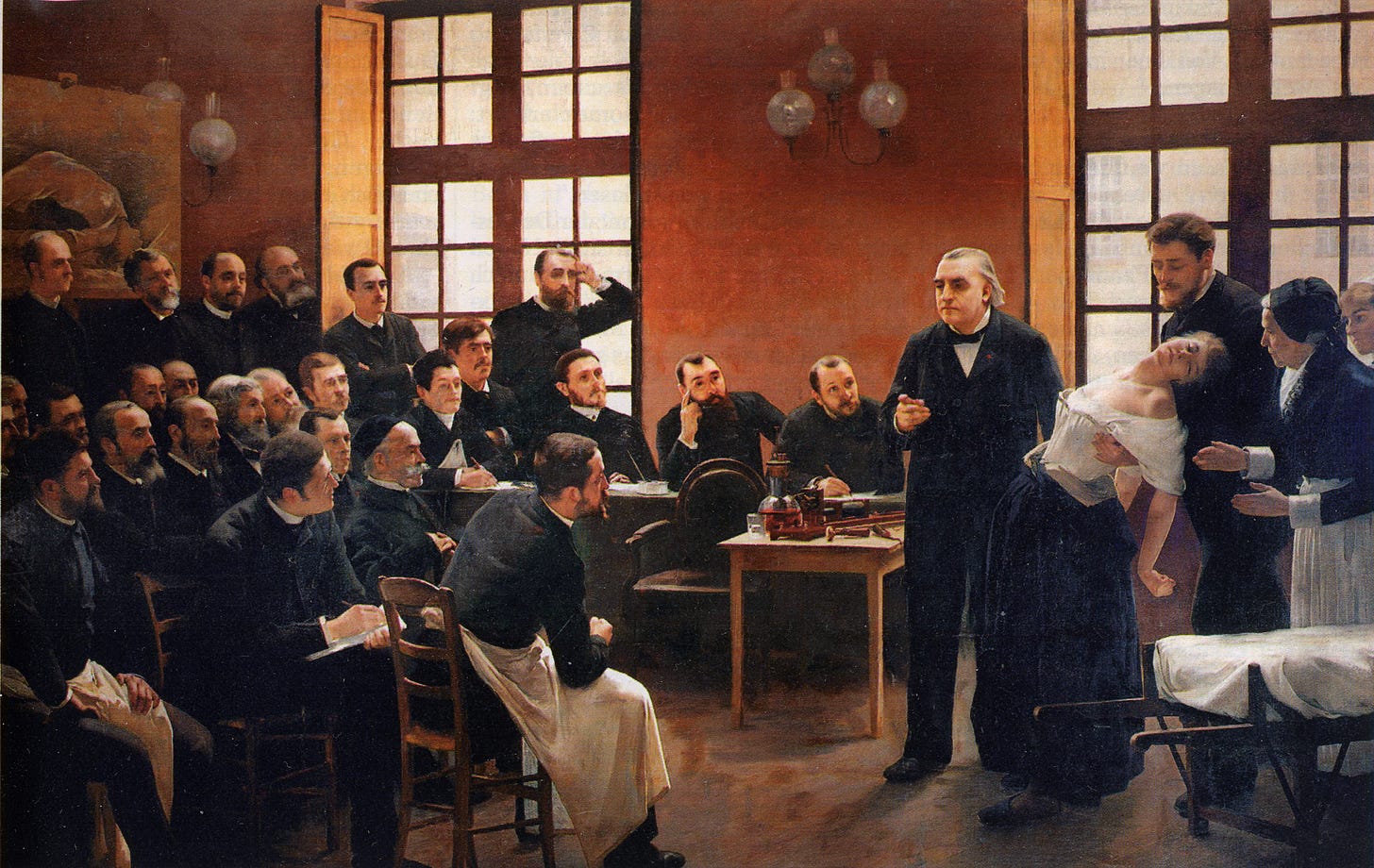

Possession and control were bound up with display — it is impossible to think of the contortions of early modern demoniacs without being reminded of the swooning, naked hysterics of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, infamously publicised in the work of Jean-Martin Charcot. The woman’s body as spectacle is both miraculous and abject, it is always constructed by and for men. Hence it is always sexual and it is always sick.

Sex, sickness, and the devil, a discursive tangle bound tightly around the bodies of early modern women. Female bodies which felt, thought, and suffered could only be understood as pathological, whether due to the influence of biology or the devil. Of course, the two were not so far apart — the womb has long been represented as a devouring mouth of hell, whilst Freud’s categorisation of the vulva as ‘Medusa’s head’ goes back to the 1500s. As historians in the post post-modern age, we’re trained not to overemphasise continuity. The past is a foreign country and everything is socially constructed. Empathy is not an academic virtue. But after months of research I keep returning to the same question — how much is really changed since the 1660s, when physician Helkiah Crooke spoke of the womb as voracious, sickening, ’greedy for seed’?10

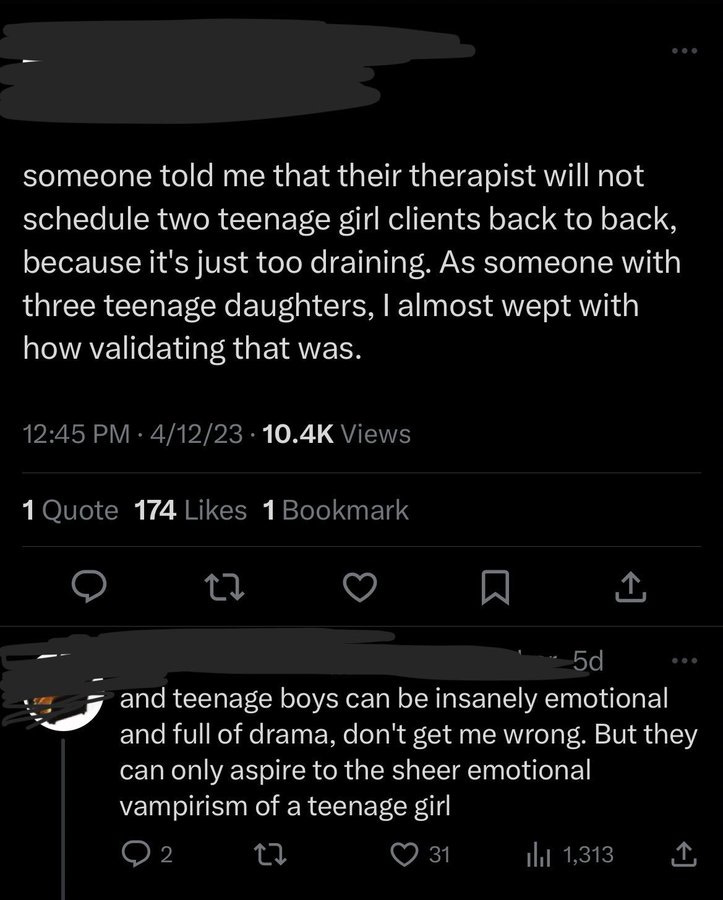

Still, we pathologise women’s disorders as hypersexual or asexual, with much of the narrative around eating disorders one of young girls ‘rejecting femininity and sexuality’ and everything from BPD to endometriosis curable in girls if only they’d find a nice man and settle down. Still, the media demonises women who defy male control over their bodies, as a brief glance at the #AmberHeard tag on Instagram demonstrates. Still, our horror movies are shaped by the deviant, devouring mouth of what Barbara Creed in the 1990s called the ‘monstrous-feminine’.11 A recent viral tweet claimed that boys ‘can only aspire to the sheer emotional vampirism of a teenage girl’, and that therapists 'will not schedule two teenage girl clients back to back, because it's just too draining’.12 The psychological voraciousness, the rapacity and inherent violence implied by ‘emotional vampirism’ feels simply like Crooke’s devouring womb updated for the post-Freudian age. There is little difference between this language and fetishisation, the user who flagged the tweet pointed out; ‘girlhood is not essentially brokenness. vilifying noncompliant daughters is just another kind of victim-blaming’.13

The dominant image of the broken girl, the sick girl, of the girl who is sick because she is a girl, is still Charcot’s hysterics or Denham’s demoniacs. She still confounds categories, defies boundaries and borders and rules. She is too feminine or too masculine, she flails or she freezes, she eats or does not eat, bleeds or does not bleed, fucks or does not fuck. But she is not real.

Sara Williams wasn’t really a vessel for the devil, just as today’s teen girls aren’t bloodthirsty vamps desperate to suck the life from their parents and therapists. It is the system which relies on her to survive, which can enact such acts of horrific violence whilst demonising the bodies of its victims, which is the true monster here.

Quoted in Boyd Brogan, ‘His Belly, Her Seed: Gender and Medicine in Early Modern Demonic Possession’ (2019)

John Fletcher and William Shakespeare, The Two Noble Kinsmen (1634)

Helen King, The Disease of Virgins (2004)

Nicholas Culpeper, Culpeper's directory for midwives: or, A guide for women (1662)

Mary Fissell, ‘Gender and the Politics of Knowledge in "Aristotle's Masterpiece”’ (2003)

Ben Johnson, The Magnetick Lady (1632)

Helen Malson, The Thin Woman: Feminism, Post-structuralism and the Social Psychology of Anorexia Nervosa (1998)

Pseudo-Aristotle, Aristotle’s masterpiece (1684)

Jonathan Sawday, The body emblazoned : dissection and the human body in Renaissance culture (1995)

Helkiah Crooke, Mikrokosmographia a description of the body of man (1615)

B. Creed, The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis (1993)

I enjoyed! I’ve been investigating esoteric feminism.

Cornelis Drebbel (b 1572) was an alchemist who invented the first cybernetic system (a self-governing oven for incubating eggs), a working perpetual motion device (powered by daily barometric pressure) and artist who depicted free thinking women teaching men science. The women are usually topless and the men are staring intently at her eyes or the work. Meanwhile, Anna Maria von Schurman (b 1607) was the first woman to attend university — but they literally made her sit in a box so she wouldn’t sexually distract the other students. (Huygens fell in love with her and wrote her suggestive poetry—suggesting she didn’t include her hands in her self portraits because they were dirty from engraving her self).

Cornelius Agrippa (b 1486) wrote 3 books on magic and a feminist tractate: “Proclamation on the Nobility and Preeminence of the Female Sex”, dedicated to the ruler of the Netherlands (a woman, Margaret, who ruled for 20 years and initiated “the ladies peace”). He wasn’t all talk— as a lawyer, he also successfully defended accused witches. His student Weyer, I believe, defended hundreds of them and wrote a book about why the whole idea of witches was really just a matter of mental illness.

Keep writing, it’s great!