On my third date with my boyfriend we planned out our dream dinner parties. There were no rules: real people, fictional people, people from across the span of human history. Anyone could be invited. It was a subtle ice breaker and a good way of getting to know each other, our preferences and passions and our politics. We argued over who was more interesting, Saint Augustine or Machiavelli or Marx. We wondered who’d get on and who’d have to be sat at opposite ends of the table, who’d have bad manners. Whether J.R.R. Tolkien would mumble into his soup, or show up in a full polar bear costume, chasing the fellow guests, as he was known to do in the 1930s. Which of Henry VIII’s wives would have the best stories to tell.

As we mulled over the logistics of convening a dinner party across time and space, we walked back to mine. It was the first night we shared a bed and I lay awake into the early hours of the morning, discomforted by the presence of a near-stranger in my single bed, taking refuge in the table setting for my dream dinner party.

We returned to the subject recently, out to celebrate personal milestones and curious to see whether our answers had changed. Maybe it was the wine speaking, but I found myself thinking differently about the dream dinner party, and in fact, the very concept of the dinner party itself. Perhaps because I’d recently re-read Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own (though I’d given Woolf pride of place at the table in both 2020 and 2024), or perhaps because of a series of artworks on show in London, at least one of which was directly inspired by Woolf’s work.

Drawn from two lectures delivered by Woolf at Newnham and Girton Colleges, then two of Cambridge’s three women's colleges, A Room of One's Own begins with a dinner. Or rather, with two dinners: the first a boozy, luxurious affair thrown at a men’s college at the fictitious hybrid ‘Oxbridge’, the second a sparsely parsimonious meal at a neighbouring women’s college, likely based off Newnham or Girton. Whilst the men feast on a grand, multi-course meal which inspires ‘the rich yellow flame of rational intercourse’, the women, like those in Woolf’s original audience, are presented with plain soup, beef, and prunes and custard, ‘nothing to stir the fancy’.1 Meanwhile (though Woolf does not dwell on the image), servants flit around the tables, passively presenting food, like the near-invisible ghosts at the edges of upper-class life in her novel Mrs Dalloway. It is the stark and unfavourable contrast between male and female dinner tables which provides Woolf with the spark for A Room of One’s Own’s examination into the conditions required by, and denied to, the woman writer. Dinner, Woolf suggests, and specifically the dinner party, is important. Important for conversation, for creativity, for the intellect, perhaps even for politics.

Woolf also has a seat at a far more illustrious dinner table than that of my imagination. In the artist Judy Chicago’s ground-breaking feminist installation The Dinner Party, Woolf is represented alongside thirty-eight other place-settings commemorating famous women from throughout history. Comprised of a triangular table divided into three wings, each 48 feet long, and resting upon a tiled floor engraved with 999 additional women’s names, The Dinner Party is a monumental feast in both senses of the word. Each table setting consists of intricately embroidered runners, gold tableware, and a 14-inch ceramic plate. Whilst each plate incorporates floral, butterfly, and vulvar imagery, each is unique, tailored to the individual life it represents; the medieval gynaeologist Trota’s features ovarian shapes, Susan B. Antony’s incorporates three-dimensional forms to represent her activist striving, whilst Woolf’s is a distinctly vulvar flower opening, symbolic of the flourishing of female creativity.

Preparatory drawings for the settings, currently on display in London’s Serpentine Gallery, reveal Chicago and her team’s research into the lives of each woman and the process of putting their stories in dialogue. Hildegard of Bingen, for example, is described as ‘Abbess, Visionary, Healer, Religious Leader, Queen of the Cloister in the 12th century when women’s power flourished briefly’. At Chicago’s table, each guest is welcomed and celebrated as a unique individual, but also treated equally as part of a group — much like the hundreds of members of Chicago’s studio team, who contributed their skills to the installation.

Not represented at the table is Woolf’s sister Vanessa Bell, a feminist artist who decades before Chicago’s installation created her own Famous Women Dinner Service with her creative and romantic partner Duncan Grant. Commissioned in 1932 for private use, the set of hand-decorated plates features portraits of fifty women, divided into Women of Letters, Queens, Beauties, and Dancers and Actresses. Bell’s artwork specifically emphasised women whose lives defied the conventions of their time, in line with the Bloomsbury Group’s progressive values, including Sappho, Pocahontas, Nell Gwyn, and Greta Garbo — as well as her sister, whose feminist lectures had been published as A Room of One’s Own three years before.

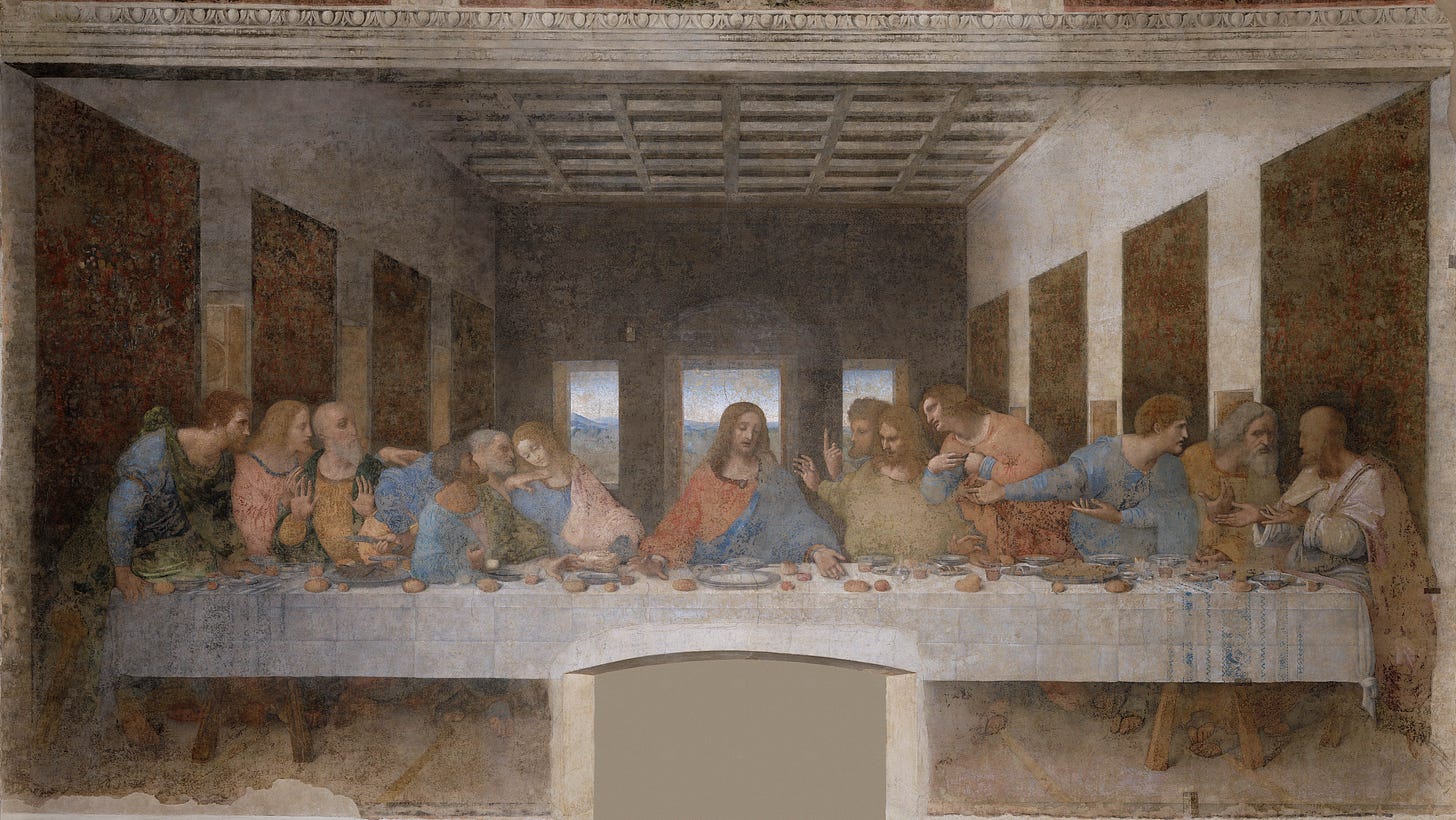

Why did both Chicago and Bell reach independently for the idea of a dinner party to showcase famous female figures from throughout history (Chicago was unaware of the Famous Women Dinner Service)? There’s a clear art historical answer to be found in the long tradition of religious artworks featuring the Last Supper, stretching back to early Christianity under the Roman Empire and reaching a peak in the Italian Renaissance. These works often depict Jesus at the moment of the Eucharist, consecrating the bread and wine upon which his disciples will both spiritually and physically feed. They also depict a homogenous group of men — white men, in the dominant European tradition — a testament to the entanglement of art history, religion, and patriarchal politics which both Chicago and Bell sought to unravel. Though of course, food is a fundamental part of human life so the tradition of depicting dinner parties goes back far further — the 2nd century Roman mosaic ‘The Unswept Floor’ depicts the leftovers of a lavish feast.

The symbolic and material fertility of these dinner table images make them ripe for reinterpretation. When revisiting the fantasy dinner party with my partner, another artwork at the forefront of my mind was Tavares Strachan’s The First Supper, which had just completed an extended display in the courtyard of London’s Royal Academy of Arts. A larger-than-life black and gold sculpture featuring thirteen Black luminaries at a long table festooned with Afro-Caribbean foodstuffs, Strachan’s work is in direct dialogue with Leonardo Da Vinci’s famous The Last Supper, a copy of which is housed inside the RA, an institution traditionally hostile to outsiders and currently interrogating its colonial past. Situated outside the gallery, the artwork literally welcomed in guests from the courtyard and the street beyond, inviting them to a raucous dinner party and a broader conversation about the questions of inclusion and exclusion, inside and outside, self and Other.

Each of these artworks — Strachan’s, Bell’s, Chicago’s, even Da Vinci’s — reveals something about the structure of the dinner party. That while it can operate as an exclusive, elitist space, it can also be a place of welcome, embrace, and openness, acting as as a way to build community and surmount borders, offering food and wine but nourishing far more than just the body, much as the Christian story of the Eucharist promises. A space of conviviality.

What does conviviality mean today? What can it promise us? I’d insert something here about our atomised society, the decline of in-person third spaces, increasingly nativist and nationalist rhetoric, and the homogenising and stratifying effect of algorithmic filter bubbles, but I don’t doubt you’ve heard it all before — not least from me. Recently I’ve become aware that my recent posts have been resoundingly negative, an accurate reflection of how I feel about the state of the world, UK politics, and our toxic online culture. But I don’t want my criticism to just be critical, an ongoing whinge about how everything sucks, actually. I want to examine new ways of rebuilding and building anew, of making a better world from the debris of the old one which so often seems to be crumbling down around our ears.

I remember the first time I read G.A. Cohen’s ‘Why Not Socialism'?’, which begins with an argument in defence of socialism disguised as an essay about a camping trip. It isn’t a perfect essay, but it’s a polemically powerful one based on a simple suggestion; that the spirit of equality and community exhibited among fellow campers (sharing their skills and property whilst pursuing their own interests together) might be scaled up to real world social politics.

It is commonly true on camping trips, and on certain small-scale projects of other kinds, that we cooperate within a concern that, so far as is possible, everybody has a roughly similar opportunity to flourish. In these contexts most people, even most anti- egalitarians, accept, indeed, take for granted, a norm of equality. So deeply do most people take it for granted that there is no occasion to question it: to question it would contradict the spirit of the trip.2

Much as the camping trip provides Cohen with an analogy for the ideal socialist society, I’d like to argue in favour of another ‘small-scale project’ as a potentially radical creative form, a model of community and conviviality: the dinner party.

The dinner party is a space of welcome. An opening of doors and arms which can enable conversation and debate, community and (re-)connection. There’s shared resources and shared labour — purchasing, cooking, and cleaning together — as well as the opening up of the private sphere to a gathered group in an age when leisure is increasingly privatised within the nuclear family and the home, or separated into online bubbles. It’s one that can step into the public sphere too — at least in my more expansive definition, which would encompass sharing communal food together at a protest or a citizen’s meeting, or holding a public picnic. In today’s world, the dinner party also serves to bring together friends and acquaintances who might not see each other regularly due to the constraints of work, place, and the demands placed on us by the online world, as well as to meet potential newcomers to an area or group. It’s a chance to put away your phone and leave the glow of the screen, indulging in an excess of food and drink and conversation, a chance to reconnect and revive.

This is probably a good place to note that dinner parties haven’t always operated entirely like my egalitarian vision — and that like Cohen, I’m allowing myself the liberties of a romantic (because sometimes someone burns dinner and someone else gets too drunk). There’s the historical institution of domestic service, with all its gender and class implications, as well as contemporary questions of access to good-quality food, space, and time. And of course, in any instance where food is served, there are politics of production and consumption — it is impossible to divorce eighteenth-century confectionary from the transatlantic slave trade just as it is impossible to divorce today’s supermarket delicacies from cheap labour and environmental catastrophes. These histories make re-imaginings like Strachan’s, Chicago’s, and Bell’s all the more powerful, their radicalism deceptive beneath a conventional art historical form. After examining their work, I’d like to think that the dinner party, whether utopian or imperfect, is as a useful political tool as it is an artistic one, and that conviviality is a vital, under-valued part of our social lives.

Again, what does conviviality mean today? Quite literally, it is defined as ‘the quality of being friendly and lively; friendliness’, from the Latin word convivium, ‘a feast’ (hence the usual connection to food-based hospitality). The root of convivium, meanwhile, is the compounding of con- ‘with’ and vivere ‘live’.3 Stripped back to the essentials, this compound lies at the core of society and political life. How can we live together? In answering this question, conviviality goes beyond the too-neutral ‘live with’ to a form of embrace of others and a welcome of difference and diversity, hence the association with hospitality. A politics of conviviality must be as hospitable as a dinner party.

Indeed, some scholars have argued for a ‘convivial turn’ emphasising the embrace of difference, diversity, and plurality and its potentially transformative social effects in the face of conservative backlash to democracy and multiculturalism, as well as a discomfort with the Eurocentric term ‘cosmopolitan’. In this literature, pioneered by postcolonial cultural theorists such as Stuart Hall and Paul Gilroy, conviviality is usually defined as the less-neutral 'living-with-difference’, though definitions do vary — the 2014 Convivialist Manifesto: A Declaration of Interdependence, defined a convivial society as one founded on ‘human cooperation and mutual respect for maximum diversity’.4 Reading even in the most amateur manner the academic debate about convivial relations — what does it really mean to ‘live with difference’? — I’m struck by how fruitful conviviality is as an analytical tool as well as in the artist’s repertoire, and how both art and theory can encourage us to see our modes of living differently. As the social anthropologist Farhan Samanani suggests in his work on convivial relations, ‘Rather than asking whether we can live with difference, we would do well to explore questions of what we might become, together.’5

It sounds so simple but it’s far from the guiding values of contemporary politics, which is so obsessed with turning inwards, excluding and turning away, with barriers and borders — both the physical ones and that which divides ‘us’ and ‘them’. ‘My Labour government will cut immigration’, says Keir Starmer, and I imagine suddenly his dinner parties, the dishes which might sit on his table so often bought to the UK by immigrants: the now-ubiquitous hummus and baba ghanoush, the curries and the koftas. I imagine the door slamming in his guests’ faces. And then I remember that even the roast chickens and the cooked breakfasts and the ice creams that we now take as symbols of ‘Britishness’ were once the products of immigrant people and immigrant ideas.6 Food is political, the consumption of food is political — though, as Woolf notes, writers considered serious ‘seldom spare a word for what was eaten’. To divorce the language of the dinner table from the political world is as inaccurate as it is impoverishing.

In Mrs Dalloway, a novel set across one day in the run-up to a party, Woolf has her protagonist Clarissa Dalloway reflect on why she enjoys throwing parties for her acquaintances.

And she felt quite continuously a sense of their existence; and she felt what a waste; and she felt what a pity; and she felt if only they could be brought together; so she did it. And it was an offering; to combine, to create; but to whom?7

The quasi-religious language here echoes A Room of One’s Own, in which the convivial conversation of a good dinner party brings about an almost spiritual revelation, a flourishing of intellect and imagination, both a coming and becoming together.

Meanwhile the wineglasses had flushed yellow and flushed crimson; had been emptied; had been filled. And thus by degrees was lit, halfway down the spine, which is the seat of the soul, not that hard little electric light which we call brilliance, as it pops in and out upon our lips, but the more profound, subtle and subterranean glow, which is the rich yellow flame of rational intercourse.8

There is precedent for this, of course. Plato’s Symposium, perhaps the most famous of his Socratic dialogues, centres on a group of men conversing about philosophy at a banquet. Could they have done so on prunes and custard, Woolf might ask? But the intellectual conversation of Plato’s interlocutors isn’t our only model of the dinner party. There’s also something frivolous about it, something excessive, which evokes images both of grand banquets dripping with Rococo centrepieces and Jell-O salad concoctions from the 1950s and 60s, both images with heavily gendered connotations (connotations Woolf is well aware of in Mrs Dalloway). This imagery reflects that the dinner party is a traditionally feminine pursuit and a celebration of feminised arts; cooking and presenting food, hosting, cleaning, ‘making house’ and putting on a display. The dinner party is an act of service, an ‘offering’ — though of course, in Woolf’s time, one propped up by the institution of domestic service itself.

To reexamine the dinner party from a feminist perspective is also to ask how we can reclaim spaces and forms of being which are both venerated when masculinised (the Last Supper, Plato’s Symposium) and demeaned when gendered as feminine. Why must Clarissa Dalloway feel ashamed of her instinct to bring people together, which the men of the novel mock? Indeed, what if she — or rather, her Conservative MP husband and his successors today — could apply that instinct to politics rather than just parties? To bring very different people together yet to cherish them equally, in ‘an offering; to combine, to create; but to whom?’.

Directly before this statement, Clarissa asks: ‘But could any man understand what she meant either? about life? She could not imagine Peter or Richard taking the trouble to give a party for no reason whatever.’ Though it is not fully articulated by Clarissa, for Woolf there seems to be more at stake here than simply a party, more a whole philosophy of connection and solidarity which is feminised and maligned by a physically and emotionally-closed off, and thus masculine-coded, society. It is this philosophy which is physicalised in Bell’s Dinner Service, a work with its own political agenda.

Bell, along with Duncan Grant and Roger Fry, was a founding member of the Omega Workshops, a short-lived craft enterprise of the 1910s which sought to unite the fine and decorative arts. A similar impetus had driven the Arts and Crafts movement, which began in the 1880s and became particularly associated with the work of William Morris, both as an artist and a social reformer concerned with the impact of mass industrialisation. Both Arts and Crafts and Omega sought to defy arbitrary distinctions between art and design, the useful and the beautiful, and in the case of Omega between artistic collaborators themselves, anonymising their works and signing them with the Greek letter Ω. In the Omega works displayed at the Cortauld Gallery in London as in the Dinner Service, Bell and Grant’s distinctive styles fuse together, expressing a blurring of personal distinctions as well as a statement of artistic equality. The harsh distinctions of early twentieth-century gender also merge together, in line with Bell and Grant’s broader interest in playing with and transgressing gender — in the portraits they created of themselves in the Dinner Service, Grant, who was queer, is represented androgynously (Interestingly, Strachan also appears in his own reimagining of the dinner party, as a quiet observer at the corner of the feast). Moreover, by creating objects that would sit as easily on the dinner table as in a museum cabinet, the Arts and Crafts movement and Omega Workshops urged their fin de siècle contemporaries to reexamine what counted as art and who counted as an artist.

Virginia Woolf saw that dinner can nourish the intellect, but that it is not always distributed equally. Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant, and the Omega Workshops, like William Morris before them, challenged the distinction between art and the useful, masculine and feminine, the individual and the collective. Years later, Judy Chicago took up those questions of access and inclusivity, revealing social assumptions alongside artistic ones and imagining a dinner party made up of an alternate canon. And today, Tavares Strachan’s work continues to interrogate this tradition by asking who gets a place at the table and by inviting diverse audiences to take a seat for themselves.

So pull up a chair. Take a seat. Add something to the feast on the table, that still life which is anything but still. Them ask yourself: who would be at your fantasy dinner party? And what are you hungry for?

I thought about making this post paid-subscriber only, but it felt wrong, especially given the subject matter. That being said, twenty-first century demoniac is reliant on paid subscribers to survive. If you’ve enjoyed my work, paid subscriptions are a way to show support and ensure I can keep writing on here — and they cost less than a coffee a month. Free subscriptions are of course appreciated too.

And if you’re in London, you can see some of the works which inspired this piece. ‘Judy Chicago: Revelations’ is on at the Serpentine Gallery. Vanessa Bell’s work can be seen at the Cortauld Gallery, as can more Bloomsbury memorabilia. Tavares Strachan’s First Supper is no longer on display at the Royal Academy of Arts, but the Da Vinci Last Supper copy is, and ‘Tavares Strachan: There is Light Somewhere’ opens at the Southbank later in June. Go make a day of it — and make sure you have dinner plans after.

Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own. There are no page numbers in these footnotes because I am feeling lazy, but message me if you want full references.

G. A. Cohen, Why Not Socialism?

Adding ‘etymology’ to the twenty-first century demoniac bingo chart I made a while back. ‘Virginia Woolf’ takes up about three squares.

‘Conviviality Vis-à-Vis Cosmopolitanism and Creolisation: Probing the Concepts’ in Oscar Hemer, Maja Povrzanović Frykman, Per-Markku Ristilammi (eds.), Conviviality at the Crossroads: The Poetics and Politics of Everyday Encounters (2020)

Farhan Samanani, ‘Conviviality and its others: for a plural politics of living with difference’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 49:9 (2023)

Diane Purkiss, English Food

Virginia Woolf, Mrs Dalloway

Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

I just finished a book called Supper Club about a woman who gathers other woman to create a supper club where they break into or host in random places a supper created from food found in dumpsters and made into dishes and then feast like animals. The book hits on how woman have to display themselves in public in a certain way and how liberating it is to be free in these atmospheres with other woman. Very good

Thank you for the read. The dinner party here feels like a metaphor for your writing. The essay behaves like one, spacious, cross-generational, slightly ritualistic.

If the table is the structure, what forms of attention would you want to gather around it?