a girl is an open question

thoughts on the girlhood aesthetic from a veteran of the girlhood aesthetic

Sometimes when I really feel like torturing myself I look through the Tumblr blog I kept as a teenager. I was on Tumblr for about five years, between 2015 and 2019, or the ages of 14 to 19, a period of my life when puberty coincided with family trauma, mental and physical health issues, and the daily torture of attending an all girls school. I don’t have very many memories of this period — as any pseudo-psychologist can tell you, mental ill health can cause mild to severe memory loss — but my Tumblr provides an archive of those blurry years in a way even my box of Moleskine journals can’t. Lengthy text posts and self-indulgent poetry, fan edits of my favourite novels, AMAs with the ‘networks’ I was a part of, and a cringe-inducing use of the tag function. At school, we submitted work to be buried in a time capsule, so future generations could look back upon the 2010s and wonder what the fuck we were all up to, behaving like that. My now-defunct-but-still-online Tumblr is that time capsule, providing a glimpse into a psyche and its social environment that now seems entirely alien to me.

Being a teenage girl is notoriously hard. Even in the 1600s, centuries before the ‘invention of the teenager’ in the 1960s, girls of fourteen and over were understood as particularly turbulent and tortured.1 Nowadays, its a trite commonplace to remark that ‘hell is a teenage girl’ or that girlhood is a form of torture. As a teenager, like so many of my contemporaries, I was obsessed with the idea and aesthetic of girlhood. It was a theme running throughout my posts and poetry, as I struggled to define my relationship to femininity on and offline. Unlike now, I didn’t feel particularly feminine, as I made limited effort with my appearance, showed little interest in boys, and my disordered eating meant I lacked both tits and a period. Looking back through my writing, though, shows that I was obsessed with navigating this troubled orientation towards being a girl. A short collection of poems that I wrote aged 16 is entitled ‘GIRLHOOD: there is nothing gentle about being girl’. Cringe away, readers, cringe away. It is pretty much what you would expect, but what surprised me is that for a girl who claimed so obsessively not to care about my appearance and proclaimed a total disinterest in all things sex, all I could write about was the oppressive beauty and sexual standards I saw girls as facing: ‘teenage girls are meant to look nice / meant to look pretty & sweet & kind / meant to look like innocence / stuck somewhere between a child & an adult…but what if i do not want to look nice?’. Imagine this posted between an emotional rant about some fictional character, and an aesthetically-pleasing classical painting like Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s The Swing, and you have a pretty strong sense of my internet presence circa early 2017.

From JustGirlyThings through Marina and the Diamonds’ era-defining Electra Heart, to art hoes and soft girls, and the hegemony of proto-influencer It Girls like Cindy Kimberly, girlhood dominated the 2010s online scene. But despite this prominent imagery, the cult of girlhood in its many forms wasn’t just centred on a particularly distinguishable iconography, but a question. We were obsessed with defining what a girl was, what a girl was told to be, who she could be within and outside the oppressive guidelines laid down by society. ‘A girl is a —’: the formulation recurred over and over again in my posts and those of other young women. A girl is a god. A girl is a gun. A girl is a void. A girl is holy. Is unholy. Is a sinner. Is a saint. Is a monster. By the time Halsey, whose albums Badlands and Hopeless Fountain Kingdom provided the soundtrack to much of this era, released ‘Girl is a Gun’ in 2021, the phrase was old news. So much of the imagery drawn upon was about power, about violence, about defiance, and this imagery complemented the broader feminist narrative — one of identities explored and championed against an increasingly oppressive political system (especially after Trump’s election), where young people could find community and consciousness raising opportunities. The images we used in our poems and edits exemplified this, particularly the reclaimed women of Greek, Roman, and Christian mythology. Persephone, Lilith, Leda, Cassandra, these were the women whose stories teenage girls were relating to and aestheticising. True to trend, I wrote a poem called ‘Andromeda saves herself’, in which the kidnapped princess makes her own escape, on the back of a sacrificial bull. Meanwhile, Persephone was widely reinterpreted not as a terrified victim of Hades, but as a powerful queen of the underworld, beautiful and terrifying in her own right. This ‘badass’ feminism wasn’t far from its counterpart, the bright pink girlboss, and now tends to elicit cringes, but much of it came from young women seeking to address patriarchal violence and build communities in a new — and aesthetically pleasing — way.

But this imagery also had a darker edge, one in which the abjection and horror of the feminised experience was romanticised or held up as a source of self-abnegation; self-harm, thinspo, and the romanticisation of mental illness flourished openly in the 2010s. I remember a friend once saying to me, ‘I wish I had a mental illness, I’m so boring’, and feeling a secret, shameful pride at the suffering which seemed to make me so unique. I kept a Pinterest board full of girls with bruised knees and shadowed eyes and never questioned the motivation behind this. If a girl was a gun, she wasn’t always turned against the patriarchal systems which kept her oppressed. Sometimes she was looking down her own barrel. On both sides of the aesthetic coin, the answer to that question — what is a girl? — was found in suffering.

Girlhood — a concept which crystallised on the Tumblr of the 2010s, the platform I grew up on — has exploded into the mainstream in recent years. From ‘hot girl summer’ and ‘hot girl walks’ to ‘girl math’ and ‘girl dinner’, ‘girlypops’ and ‘babygirls’, ‘I’m just a girl’, ‘eldest daughters’, ‘female rage’ and a thousand other memes, the cult of the girl has saturated every corner of internet life in pastel pink. This new lexicon of girlhood is accompanied by a recognisable set of images, drawn from TV and film (think Barbie, Euphoria, Little Women, and Marie Antoinette to name four very different sources), music (IT GIRL by Alyiah’s Interlude being just the latest), the natural world (deer, bunnies, butterflies), literature and art. Lifestyle matters too: ballet, self care, romance, religion, and traditionally ‘girly’ tasks are decidedly in, whilst high and low fashion have both come to reflect the zeitgeist; think pink, frills, ruffles, and bows. In her video essay on the subject, fashion and pop culture critic Mina Le noted that this aesthetic has two aspects — the in-your-face pink of Barbiecore and Selkie dresses, and the muted, ballet-inspired bows and ribbons of coquette-core and its derivatives.2 They may differ in saturation, but they are drawn from the same palette.

There are many reasons why women, both young and old, have sought refuge in the imagery of girlhood. The world has been harsh lately, particularly for women. In the West feminist movements like Me Too have seen little tangible gains — the reverse, in fact, most egregiously the chipping away of abortion rights. It’s no wonder we want to retreat into what brings us comfort. A nostalgia for girlhood may seem like looking back to a time before patriarchy tightened its grip around us, but childhood and adolescence is in fact the time when that grip takes hold. Judith Butler describes the production of gender difference as a social mechanism; the process of ‘girling’ that begins at the moment of birth, when the doctor proclaims ‘it’s a girl!’, and which continues throughout our lives.3 Gendering in this way is performative, we are positioned as girl and become girl through the socially-prescribed acts we perform almost automatically. So many of these acts are acts of beautification, of prettification. In Simone de Beauvoir’s famous formulation, ‘one is not born, but becomes a woman’. This act of becoming begins with girlhood, and thus its aesthetics is loaded with symbolic meaning. Girlhood, after all, is the period when we first become sexual objects, a harsh reality which Lolita, coquette, and nymphet fashion plays with to both alluring and disturbing effect.

From ‘Hi Barbie!’ to edits of Angelina Ballerina, bows on bunnies and Brandy Melville, much of today’s ‘girlhood’ is bound up with returning to a childish innocence, free of responsibility. But we cannot return to innocence, we can only mimic its appearance, affect its mannerisms. And this flight into girlhood is not a neutral one. De Beauvoir writes that women display submission to men’s definition of themselves, become complicit in their own Othering and accept the limited privileges and comforts it brings.4 In doing so, they infantilise themselves, reject the autonomy as well as the anxieties of modern life.

‘Refusing to be the Other, refusing complicity with man, would mean renouncing all the advantages an alliance with the superior caste confers on them….Beside every individual’s claim to assert himself as subject—an ethical claim—lies the temptation to flee freedom and to make himself into a thing: it is a pernicious path because the individual, passive, alienated, and lost, is prey to a foreign will, cut off from his transcendence, robbed of all worth. But it is an easy path: the anguish and stress of authentically assumed existence are thus avoided.’5

It is this easy yet dangerous path which we are tumbling down.

It is unsurprising then that this flight into girlhood has occurred alongside the rise of what Emmeline Clein first termed 'dissociative’ or ‘disassociation feminism’, a sarcastic apathy and numbness towards real world issues and relationships epitomised by the Red Scare girls and season one Fleabag.6 Dissociative feminism rejects reality, chooses to be numb instead of confrontational, refuses to fight back. Makes suffering personal — a part of its cool girl, couldn’t care less persona — rather than political.

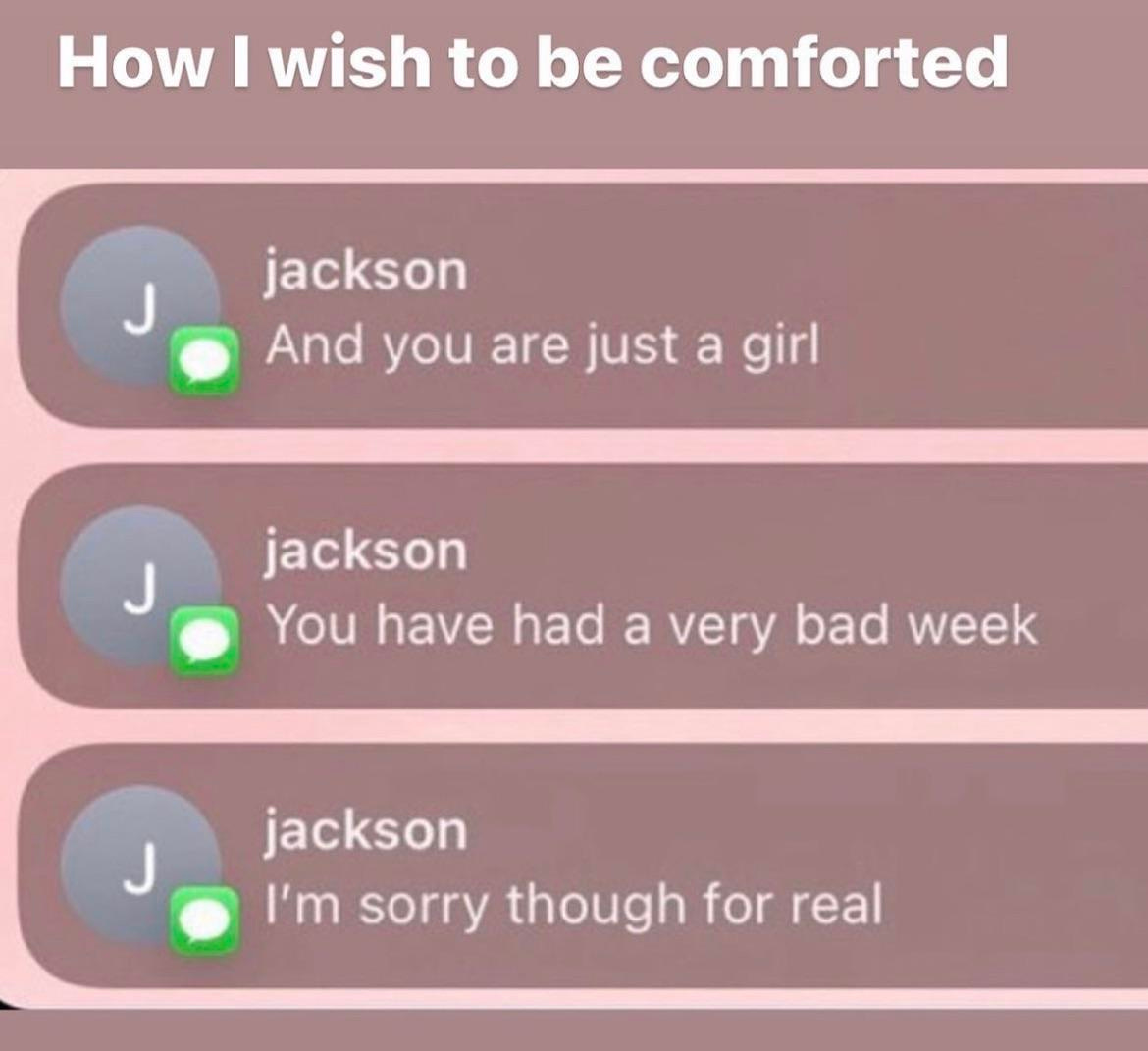

Fragile butterflies, baby deer, bunny rabbits with pink bows in their ears. These have always been the symbols of fragility, and young women today have embraced them. They are cute, innocent, imperilled by the world and unable to stand up to it alone. Kittens not cats, bunnies not hares. Mature animals do not fit the girlhood aesthetic, only babies. They require protection. They are easily hurt — they inspire the desire to harm as well as to protect. The innocence of a child is also its dependance, on other women in particular, their mothers, who maintain what Rachel Cusk calls ‘the family drama’, that tenuous narrative of functional family life.7 Dependence also on men, on the paternalistic face of patriarchy which permits femininity only when it can protect/control it, when it can be picked up and held in one hand. I just want a man to make my decisions for me, twenty-year-olds say on TikTok, choosing to take De Beauvoir’s ‘easy path’ and dissociate through #tradwife or #futuretrophywife, #sugarbaby and #stayathomegirlfriend. It’s not unfeminist. It’s not that deep. A series of text messages from a woman and her partner goes viral, him comforting her for having a bad week. ‘You’re just a girl’. To be a girl is to struggle? To be a girl is to be weak, unable to face the real world? Here again is the complicity, the flight from freedom, the making of oneself ‘into a thing’.8

Not to praise 2010s Tumblr culture too much — it was rammed full of contradictions and prejudices, self-hatred and the glamorisation of downright dangerous behaviour — but I do feel we’ve lost something now girlhood has hit the mainstream. Something critical, in both senses of the word. Something which knew that yes, it is that deep. Rather than paying attention to the female interior, beneath the veneer of girling, today’s mainstream girlhood culture seems to focus solely on the exterior, external experience of girlhood, particularly as it is bound up with beauty. Whilst a more thoughtful engagement with girlhood may still thrive in certain circles, the popular feminist criticism and art that thrived in the 2010s has been replaced by a hollow aesthetic and preoccupation with the very markers of girlhood that were once rejected as patriarchal impositions — beauty, youth, innocence, fragility, appeal to the male gaze.

The darker side of exploring girlhood has remained, but its worst aspects have been magnified and increasingly prettified. The coquette aesthetic, for example, often intersects with pro-ana content online, as does the ‘romantic’ and catholic-core or religious aesthetics. As numerous commentators have argued, it has now become more insidious, as a form of ‘girl phrenology’ takes off. Phrenology, the study of facial structure as an indicator for moral character, is a universally discredited nineteenth-century pseudoscience…and a twenty-first century TikTok trend. Are you fox pretty, cat pretty, or bunny pretty? Do you have angel skull or a witch skull? What percentage of feminine are your facial features? As Miles Klee points out in his Rolling Stone article ‘Why are the girlies so into phrenology?’, phrenology has long been a tool for far-right fascists in the darkest recesses of the internet, seeking to discredit those who threaten their racial and sexual prescriptions as ‘genetically-inferior’.9 But Klee doesn’t really answer the question his article poses — why are the girlies suddenly so into phrenology?

The most recent form — girl pretty versus guy pretty — posits moral superiority for women who are ‘girl pretty’, i.e girls girls, whose appearances appeal to other women, and sexual or romantic superiority for ‘boy pretty’ women who easily cater to the male gaze.10 A viral chart from earlier this year showed ‘girl pretty’ and ‘boy pretty’ women side-by-side, whilst women on TikTok pose and ask their followers to define them as one or the other.11 The problem? Well, there are many, not least phrenology’s status as a racist, sexist, classist pseudoscience involved in the historical justification of slavery, forced sterilisation, anti-Semitic violence, and the demeaning of women as hysterical. But also — none of the ‘girl pretty’ or ‘guy pretty’ women really look that different. They’re all conventionally beautiful, all ‘tens’.

There’s been plenty of valid criticism picking apart the pitting of beautiful women against one another, and defining women by their appeal to men, but let us go a step further. Not everyone is conventionally ‘pretty’. Not everyone has to be conventionally ‘pretty’. Until we free ourselves from that way of thinking, which is so bound up with sexist, racist, transphobic beauty standards, we will never truly be liberated from the male gaze. Yet instead of criticising those beauty standards, girl phrenology reiterates and emphasises them, albeit with different names, reinforcing old categories of privilege under the guise of a fun new trend. When femininity’s ‘angelic’ attributes are aesthetically reinforced everywhere from Pinterest boards to the runway, what does it mean to be told you have a ‘witch’ rather than ‘angel’ skull?

‘Pretty’ is increasingly the sum total of the girlhood aesthetic, its core tenet and ultimate aim. Sure, there’s the sisterly solidarity of Greta Gerwig’s Barbie Movie, which left me feeling warm and fuzzy, but there’s also the multi-million dollar marketing campaign that harnessed these female sentiments to sell a bright pink version of everything under the sun. Entangled in consumer capitalism, #Barbiecore was all about the look. In the movie itself, Barbie’s first reaction to experiencing failure is to attack her own appearance, to see herself as ugly. For women, to be ‘ugly’ is in a way a failure — a failure to conform, to meet the standards that patriarchy imposes upon us, the standards that are articulated from the very first moment we are handed a teddy bear in a pink dress and bow, with blush on her fluffy cheeks. To me, girl phrenology is just another way to police access to beauty, and therefore privilege, a backlash against the brief moment of body positivity which flickered in and out of existence in the mid-2010s. It is a complicity with patriarchal body standards, self-objectification concealed as self-definition: ‘she often derives satisfaction from her role as Other.’12

The contradiction at the heart of female beauty is that it is considered an essential part of femininity, necessary for women to survive under patriarchy (whether by elevating one’s value in the sexual market or simply avoiding careless cruelty and discrimination), yet is systematically devalued as frivolous and a source of ridicule.13 Beautification is a form of what scholar Debra Gimlin calls ‘bodywork’:

‘All societies require that their members do work on their bodies to transform them from the ‘natural’ state to one that is more explicitly ‘cultural’. However, social expectations concerning the type and extent of such efforts are not uniform across all groups’14

Women are expected to pay a particularly high level of time, money, and effort on bodywork. Bodywork aimed at making the female body beautiful, bringing it line with cultural norms, is time-consuming and often painful, eating into the time and energy girls use to define themselves and becoming an integral part of that self-definition.

In the girlhood aesthetic, beauty is bound up with pain and pain becomes beautiful — think bloodied ballet slippers, corsets, laborious beauty routines. ‘Girl dinner’ as a cigarette and iced coffee. An image of satin ribbon laced through skin. This prettification of female suffering has a long history, encompassing both the Romantic ideal of the tubercular woman and 90s heroin chic. It is now a key tenet of our popular culture, from Black Swan to Euphoria’s Cassie Howard, and with social media it has become even more linked to the performance of bodywork — think lengthy GRWM beauty routines and 5am cardio sessions.

By coupling ‘suffering’ and ‘girlhood’, we are performing an act of gendering which makes suffering, pain, and hurt key characteristics of femininity, an attribution which has long been used to oppress us. If a woman is frail and fragile as a china doll, she must be kept on her shelf. To be female is to be beautiful and to be beautiful is to suffer and to suffer is to be female. Can we never escape the loop? Can we not imagine ourselves outside these narrow bounds, imagine other, more radical acts of becoming?

Whilst on Tumblr, adolescent girls were the primary creators, thoughtfully exploring their own identities, much of the ‘girlhood’ aesthetic and its related discourse is now generated by those who are no longer girls, who have passed their teenage years and entered a fraught, fragile adulthood in an uncertain world. ‘I’m just a twenty-three year old teenage girl’ has become a common refrain, especially for those of us who lost the end of their adolescence to lockdown. Why is it so hard for older women to let go of their girlhood? In a interview earlier this year, fashion designer Sandy Liang, whose whimsical yet edgy designs are a staple of girl fashion, said that her style arises from nostalgia about ‘precious childhood naïveté’. ‘I’m obsessed over something that I can actually never return to.’15 It makes for great fashion, but why do we want so desperately to return to a state of innocence, of dependance, of fragility? Is the romanticisation of this state reconcilable with a radical, liberating, challenging feminism? As De Beauvoir reminds us, we can be complicit in our own subjugation. To free ourselves from that subjugation we may have to challenge the aspects of femininity which obsess us, comfort us, bring us pleasure. We must refuse the allure of femininity even if it brings us pleasures under patriarchy; I am reminded again the TikToks of young women begging to be affirmed as ‘girl pretty’ or ‘boy pretty’. De Beauvoir again:

‘The beauty of flowers and women’s charms can be appreciated for what they are worth; if these treasures are paid for with blood or misery, one must be willing to sacrifice them.’16

Girlhood is the period when we are supposedly most free to define ourselves, yet most confined by the social processes of gender, by the acts of ‘Othering’ and ‘girling’. The viral montage of Cassie from Euphoria, waking up at 4am to make herself beautiful for a cruel high school boy who doesn’t even notice her in the corridor and proclaims his desire to control her appearance and sexuality, exemplifies the intermingling of beauty and pain, aesthetic and reality. The montage is (mostly) critical, ironic, but it quickly became a trending TikTok template for girls to show their extensive beauty and self care routines, their performative bodywork. We may be conditioned to give up our autonomy, but at least we can control our appearance.

As girls, we are desperate to become something. Yet with every passing moment, what we can become is more and more constrained, more and more of our time devoted to being beautiful, or at least acceptable. How we look, rather than who we are. As women, facing the often harsh realities of daily adult life, we look back to adolescence as a period where becoming was still a possibility. But even if it was ever really that, we can’t get it back. All that is accessible to us now is the aesthetic.

In a bright upstairs room of the Wallace Collection, Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s rococo painting The Swing takes prize position. This erotically-charged, sensually opulent painting of two lovers in a garden has long been famous, but it has recently become one of the images adopted online as emblematic of the ‘girlhood’ aesthetic, a mainstay of Pinterest boards and coquette, romantic, or Regency-core instagram posts (anachronism notwithstanding). The girl on the swing is youthful, skin china-white with rose-tinted cheeks. Her slender body is dwarfed by a surfeit of pink ruffles and tulle, and a floral straw hat precariously slips from her head. White stockinged feet emerge from the dress, teasing her lover, whose ecstatic expression — and the alternate title, The Happy Accidents of the Swing — makes a whole lot of sense when you realise that eighteenth-century women would not have been wearing underwear beneath her shift.17 The legs are just a little too long, a little warped behind the skirt, heightening the erotic tension they symbolise.

Every time I visit the Wallace Collection, a crowd forms around The Swing, mainly of young women taking photos. It’s a great painting, but tucked in the corner beside it is another image of a young woman by Fragonard, The Souvenir. A girl stands half in shadow, carving an initial into a tree trunk, a look of dreamy concentration on her face. I love this painting, and am willing to brave the crowds around The Swing to gaze on it again and again. Whether the subject is writing her own name or a lover’s, it is a moment of quiet solitude as a woman carves her own mark into the world. It is beautiful, sure, and very much feminine, but it is a small canvas, subtle and understated, a tiny insight into the girl’s rich inner life.

Today’s ‘girlhood’ discourse and the aesthetic which has sprung up around a narrowly-defined, ambiguously articulated version of femininity stops short at The Swing. It oohs and ahhs, appreciating her sumptuous gown, her flawless skin, the sensual and romantic ideal she represents. Perhaps it notes the contortions which go into constructing beauty and maintaining its facade — the impossible legs, the pale skin, the perspective. Perhaps it takes stock of the lover in the corner, the charged angle of his eyes, and thinks ah, the male gaze, or maybe it sees her as a girl’s girl, in a world of her own.

But it is a perspective which is conditioned by the aesthetic, the immediate appeal of the painting, its flourishes and frills like Valentines candy, its pastel palette and lush backdrop. In beautifying, it limits. It is a vision of girlhood which rarely looks outside the frame.

Congrats if you got this far. I want to be clear that I enjoy and indulge in the girlhood aesthetic myself — I’m writing this from a very pink bedroom, on a laptop covered in stickers of butterflies, neoclassical paintings, and Anya Taylor Joy, with ribbons tied to my jeans. I just think its worthy of more critical analysis than the ‘it’s not that deep’ crowd would like to pretend.

If you liked this post, you can subscribe or pledge a donation to this blog - it’s much appreciated.

I wrote about premodern teenage girlhood and its intersections with witchcraft earlier this year:

dispossessing pathological femininity

TW: discussion of sexual assault, rape, disordered eating in a historical context. In the infamous Denham exorcisms of the 1580s, 15 year old servant Sara Williams and her older sister Friswood were forcefully dispossessed by a group of Jesuit priests residing with their employers. Shortly after joining the Denham household, Williams had fallen unwell. S…

Mina Le, ‘Why is everyone dressing like a little girl?’, YouTube video (2023)

Judith Butler, Bodies that matter (1993), p. 7

Simone De Beauvoir, The Second Sex (1949), p. 21

De Beauvoir, p. 30

Emmeline Clein, ‘The Smartest Women I Know Are All Dissociating’, Buzzfeed (2019) — https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/emmelineclein/dissociation-feminism-women-fleabag-twitter

Rachel Cusk, Coventry (2019), p. 35

De Beauvoir, p. 30

Miles Klee, ‘Why Are the Girlies So Into Phrenology?', Rolling Stone (2023) — https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/far-right-phrenology-physiognomy-spread-hate-1234808413/

See KnowYourMeme for some further examples https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/girl-pretty-vs-boy-pretty for examples

I highly recommend the episode that the Polyester Podcast girls did on this topic — and in general, they’re a great example of deeply critical thinkers who are also 100% girlies

De Beauvoir, p. 30

I wrote about the history of makeup and its apocalyptic connotations in my last post:

making it up

I was never a makeup kid. My mum owned one Clinique eyeshadow palette and couldn’t paint her nails, so unlike the it girls immortalised in Vogue’s beloved Beauty Secrets series (‘everything I know about makeup I learnt from my mom’ ad infinitum) I didn’t grow up entranced by the world of cosmetics. I know from a childhood diary that I loved lip gloss at…

Debra Gimlin, ‘What Is ‘Body Work’? A Review of the Literature’, Sociology Compass (2007)

‘The Big Business of Dressing Like a Little Girl’, New York Times (2023) — https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/09/style/sandy-liang-baggu.html

De Beauvoir, p. 861

‘Fashion in The Swing’, The Wallace Collection — https://www.wallacecollection.org/explore/explore-in-depth/fragonards-the-swing/origins-of-the-swing/fashion-in-the-swing/

I admire how much detail you put into this. So very good.

Great artistic references!