I was never a makeup kid. My mum owned one Clinique eyeshadow palette and couldn’t paint her nails, so unlike the it girls immortalised in Vogue’s beloved Beauty Secrets series (‘everything I know about makeup I learnt from my mom’ ad infinitum) I didn’t grow up entranced by the world of cosmetics. I know from a childhood diary that I loved lip gloss at the age of seven, and I distinctly remember owning a bright blue, Britney-esque eyeshadow that screamed noughties camp. But it didn’t stick. By the time I was nine, I no longer wanted to be a pop star but a poet, my favourite colour was black, and I was aggressively averse to all things girly — makeup included.

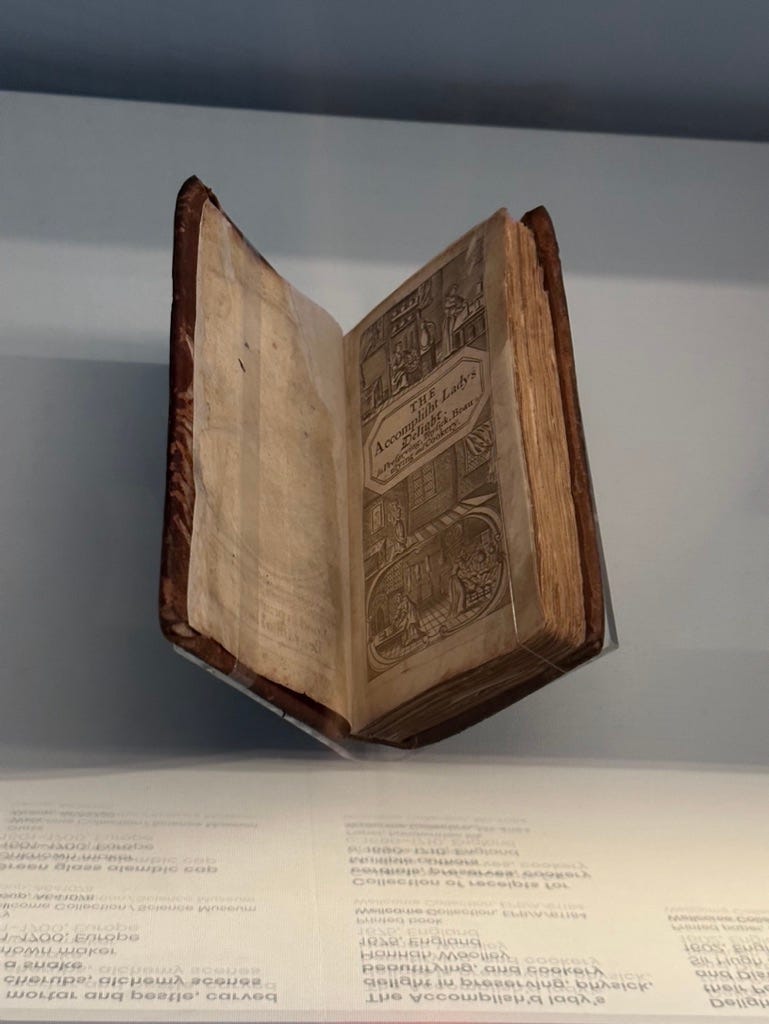

The Wellcome Collection’s new exhibition, entitled The Cult of Beauty, explores beauty culture as a consistent, yet culturally-conditioned, aspect of human life.1 Spanning from Greco-Roman statues of Aphrodite, now white-washed by time, to Barbie’s bleach blonde hair and inch-wide waist, the exhibition is a revealing journey across time, demonstrating just how much changes, and just how much stays the same. There are male figures and male beauty routines in the exhibition — powdered cheeks, wigs, and ridiculous beards all feature — but the picture of cosmetic culture and the debates around it that Cult of Beauty paints is a feminised one. From the recipe books that early modern women used to record medicinal, culinary, and cosmetic recipes like Hannah Wooley’s 1675 The Accomplish'd lady's delight in preserving, physick. beautifying, and cookery, to a wall of filtered selfies and GRWM TikToks, the target audience for cosmetics has always been overwhelmingly female. In the age of the selfie, women can’t escape cosmetics — and it seems that we never could.

I didn’t wear makeup consistently until I was in my late teens — the Sixth Form ID that I cut to shreds a few months ago showed a pallid girl with dark shadows and sunken cheeks, acne dotted across her forehead. I hated how I looked, but (despite filling in my brows with a far-too-dark pomade) I saw concealing that as an anti-feminist act, a distraction from far more important pursuits like studying and activism and posting no-caps poetry filled with self-loathing on Tumblr. I was stuck between two ideas of what I wanted to be like, and who I wanted to be. At university I went the other way; unable to leave the flat without concealer, terrified of what the other students would think of my ‘natural’ appearance. In the years since I’ve come to see makeup as a medium not just for concealment, but for experimentation, for play, for beauty and sensuality, and as a mask which better enables me to present my ‘public face’ to the world. I’m still uneasy with it, though; I feel the pressure to look perfect, struggle to accept my natural features when Instagram is constantly pushing beauty content my way, and spend huge amounts of money on trending retinols or new mascaras. Like many women, I have difficulty even knowing what my face ‘truly’ looks like, which deeply influences how I feel about myself. I recently read about acne dysmorphia, a variant of body dysmorphia where people find themselves consumed by thoughts of how bad their acne is, thoughts which do not reflect the true picture of a person’s appearance.2 Every time the simmering debate about whether wearing makeup can ever be feminist simmers to a boil, I feel guilty, like I’ve discarded the principles my younger self claimed to hold, even if she was only doing so as a cover for her own self-hatred.

Feminists have struggled with the question of makeup and cosmetic procedures long before the advent of contouring and the BBL. Professor Jill Burke, who advised on The Cult of Beauty, writes of the cosmetics debate in Renaissance Italy: ‘Debates over female beautification have tended to be complex and seemingly self-contradictory, on one side insisting on women’s freedom to adorn themselves as they choose, and on the other arguing that beauty culture is nothing more than another pressure on women to conform.’3 Burke recalls the words of Laura Cereta, a fifteenth-century Italian proto-feminist and humanist who advocated women’s education, but felt ‘ashamed of the irreverence of certain women’ who ‘strive to seem more beautiful’, criticising ‘the weakness of our sex in its delights’.4 To Cereta, like the radical feminists of the 1960s and 70s, any indulgence in beautification was letting down the real female cause.

Cosmetics have always been loaded with meaning, and not just for those who use them. Cereta may have demeaned cosmetics as an obstacle to the female cause, but male authors of the same and later periods have seen cosmetics as an emblem of innate feminine depravity, bordering on the grotesquely abject. The Cult of Beauty also includes Daniel Hopfer’s 1520 print, Death and the Devil Surprising a Worldly Woman, in which the skeletal, morbid figure of death peers over the shoulder of a glamorously made-up woman, who is in turn staring in a pocket-mirror. The image is a classic memento mori but with a pointed message — the carefully cultivated beauty of vain, worldly women, will eventually come to dust and ashes. It warns the viewer of their own inevitable demise, but it does so by poking fun at the beautification practices of the ‘weaker sex’.

In Hopfer’s print, the counterpart to the beautiful woman is the grotesque skeleton, and the thin line between the two can easily fray. This anxiety is reflected across the cosmetics debate in the premodern period. In Thomas Jeamson’s treatise, Artificiall embellishments, or Arts best directions how to preserve beauty or procure it, published at Oxford in 1665, the author provides substantial advice for women looking to beautify their complexions and maintain an ideal weight. Startlingly, for a text on makeup, the main theme and image of Jeamson’s work is death and dying. Discussing body weight, Jeamson notes that ‘excessive gluttony makes a Lady such a mountain of greasie mummy’ (mummy being a medicinal substance created by the crushing of corpses) whilst thinner women are ‘breathing Skeletons that carry Lent in their face at a Christmas feast, and look so meagerly that their Confes∣sours, since they have nothing leaft but skin and bones’, their flesh ‘eaten up.’5 As in Hopfer’s print, misogyny and anxiety over mortality go hand in hand.

Historian Sarah Pennell has noted the concurrence of Jeamson’s publication with outbreaks of plague in the surrounding areas. As we know from our experiences with Covid, plagues make manifest the fragility of life and the omnipresence of death, and no amount of unnaturally imparted health, youth, or longevity can escape it. Pennell writes: ‘Morbid imagery, medical discourse and hence by implication the plague itself provide a potent sub-text to the entire book. The plague was the unmentionable everybody tried to forget, the repressed but nevertheless ever-present threat from which everybody tried to escape. Unmentionable though it was, in the text under discussion it is plainly present in the shape of recurrent lexical clusters impregnated with the horrors of death.’6 Is the same true today? Beneath the endless new beauty products and extended skincare routines (five steps! ten! fourteen!), the incessant advertising and the rebranded beauty standards, are we all just terrified of dying?

It has sometimes been assumed that the modern world is moving towards a grand and unprecedented victory: the defeat of death. Billionaires and longevity start-ups work towards extending the natural human life span — for an elite few, most famously tech entrepreneur Bryan Johnson, whose plan to ‘live forever’ involves taking blood transfusions from his eighteen-year-old son7 — whilst ordinary mortals slather on retinols and barrier creams to prevent the merest suggestion of a wrinkle. Whilst not quite the radical life extension envisioned by billionaire entrepreneurs, the average life is estimated to be ten years longer by the end of this century.8 And whilst horrifyingly deadly, Covid wasn’t the Black Death — it didn’t demolish the entire social infrastructure binding us together.

Yet we’re not so far from Jeamson’s apocalyptic sentiment as we at first appear. Unlike in the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries, now, the world actually is ending, with climate changing rendering the world uninhabitable one crisis at a time. What’s the point in radical life extension if there’s no world left to live that life in? For the religious Europeans of the early modern era, accepting one’s imminent worldly death was in fact defeating death — claiming a spiritual position in the Kingdom of Heaven, and eventually experiencing bodily resurrection at the Second Coming. The perfection of the body was nothing compared to the perfection of the soul. But for us, today, death just means…well, death. Why not be perfect while you still have the time? Why not strive to eke back a little more of that time, or at least give the impression that you have?

Like any good historian, I can tell you that a cultural trend reveals a cultural concern. The Renaissance debate over cosmetics spoke to anxieties over artifice and concealment, particularly among women, who could use makeup to gain a kind of power over men and the aging process which restricted their social value. Death threatened everyone, but for women, whose position in society relied upon their fertility and desirability in the marriage market, physical degradation posed a powerful threat. And so, they resorted to making it up. Some women, like Laura Cereta, saw that as a threat, whilst others embraced it as a power. Today’s cosmetics are not just an affirmation of life and youth but a terror of their opposite. Do people really want to live forever, or do they just want to deny the real effects of aging and death written on their faces, and the sexist and ageist discrimination that brings? On the internet, ‘Instagram face’ and ‘AI face’ blur together into one, as real humans adopt cosmetic and surgical procedures to make them look less, not more, real — as empty of humanity as a generic sexy woman generated by an algorithm. Men online joke about how with these new AI girlfriends, women will be replaced. For us in particular, the routine is endless, the desperation insurmountable. Conceal your wrinkles, your exhausted dark bags, contour away your cheeks and gua sha your jowls. Become young again, erase the years of experience and emotion, the very things that make us human. We are terrified of physical degeneration, but our bodies are born into a state of degeneration. Each breath takes us closer to death. Especially in a world which is hurtling into climate catastrophe, the natural beauty of the earth’s own face disfigured, that reality is impossible to deny.

In the early modern era, cosmetics were seen as a sort of female alchemy, and modern makeup still sells us the same promise: do this, and you can live forever. But we can’t live forever. We can only slap on some concealer, curl our lashes, and set out to face the next and possibly last day of our lives.

The Cult of Beauty runs at the Wellcome until 28th April 2024, and I highly recommend a visit: https://wellcomecollection.org/exhibitions/ZJ1zCxAAACMAczPA

https://www.acnesupport.org.uk/emotional-support/skin-discolouration-and-staining/

Jill Burke, How to be a Renaissance Woman, (2023) p. 55

Ibid, pp. 56-7

Thomas Jeamson, Artificiall embellishments, or Arts best directions how to preserve beauty or procure it (1665)

Sara Pennell, "Deformity's Filthy Fingers: Cosmetics and the Plague in Artifidall Embellishments, or Arts Best Directions How to Preserve Beauty or Procure It (Oxford, 1665)" in Didactic Literature in England 1500–1800 (2003), p. 143

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/sep/14/my-ultimate-goal-dont-die-bryan-johnson-on-his-controversial-plan-to-live-for-ever

https://www.ft.com/content/60d9271c-ae0a-4d44-8b11-956cd2e484a9