soft power americana

digital hegemony & the americanisation of the internet

Lately my corner of the internet has felt very American. For the last few weeks, viral videos of sorority rush recruitment drives have flooded my feeds, a mix of peppy pink-clad women performing cheerleader stunts for TikTok and veteran sorority members warning that it’s all much more serious than it looks. The tired debate about British versus American food has reared its ugly head after an American tourist tweeted a photo of a dry pork pie, meaning once again we all have to hear the same old equally-dry arguments about how Brits can’t stomach flavour, made by people who pass out at the taste of Coleman’s Mustard and ignore the influence of multicultural immigrant cuisines on our national dishes.

In the world of stan culture, there’s the luminous Chappell Roan, her star on the rise after the success of her album ‘The Rise and Fall of a Midwest Princess’ about her experiences of moving from small-town Missouri to LA, and the less-than-luminous Taylor Swift, whose drawn-out Eras tour finally comes to an end this month. Elsewhere, the continual slew of terminally-online pseudo-intellectual cool girl drivel churns out of the New York ‘scene’, most lately in the delightfully twisty and morally rancid ‘Hegelian E-Girl’ saga (None of that mean anything to you? My friend Kate Bugos wrote a great primer for girl online). Then there’s the inescapable rumble of the US presidential election, both serious political commentary and the unfunny question of whether Kamala Harris is ‘brat’. Personally, I think it’s starting to sound like we’ve all been hit in the head with a coconut falling from the proverbial tree, but then again, what do I know?

And look, I’m British. We had our internet moment in the sun back in the days when Sherlock and Doctor Who and One Direction and emblazoning ‘Keep Calm and Carry On’ on a tote bag were considered vaguely cool rather than entirely cringe. Not to mention the pomposity of my complaining at all, given the on and offline predominance of the English language, and the inflated self-regard with which British commentators discuss themselves and their place in the world. Lately, though, it has felt impossible to escape America, and its outsized, loud-and-proud influence on online culture. You can’t just mute it, and even if you do, you can’t escape it.

This was repeatedly driven home during the horrific far-right riots which swept across the UK at the start of August, when American tech billionaire, owner of X-formerly-known-as-Twitter, and all-round bad person Elon Musk weighed in to repeatedly incite unrest. Watching Musk gleefully post about how ‘civil war [in the UK] is inevitable’, I felt that he didn’t see Britain as a real country at all, but simply a virtual playground or the set of a video-game for him to LARP around in — an attitude far more harmful when applied by the powerful to developing countries across the globe, particularly those in which the U.S. has commercial or colonial interests. For powerful Americans like Musk, the U.S. of A is the only real country, and the rest of the world just a simulation, a Westworld or Don’t Worry Darling style space of play and war and escape (the stark image of sole Palestinian-American congresswoman Rashida Tlaib protesting during Netanyahu’s Congress address last month springs to mind, as does that of Hollywood stars like ‘Captain America’ Chris Evans signing bombs, whether fake as claimed or real). And as an ordinary internet user from anywhere but the U.S., sometimes it’s hard not to feel the same — that America is the real world, the biggest and the brightest and the most important, and that the rest of us are just operating in its cultural shadow. That ‘culture’ itself is American culture.

There’s a term for this, ‘Americanisation’, used by sociologists to refer to the influence the U.S. exerts on other states through cultural soft power. Americanisation is not a neutral process, but a geopolitical strategy used to cement American influence worldwide. From the end of the 1940s, the booming U.S. economy exported its media, pop culture, food and drink, technological and other innovations, and business practices to a world still reeling from the Second World War, alongside more obviously political measures such as the Marshall Plan of economic aid for Europe and the 1949 establishment of NATO. As the Cold War cast a chill over the globe, Americanisation was an explicit effort to counter the spread of Soviet influence in the USSR and China, and their spheres of influence, and was often effected through American brands and the capitalist market. Coca-Cola, one of the largest companies in the world and as symbolically American as the Stars and Stripes, played such a role in this effort that commentators began to refer to ‘coca-colonisation’. In the 1940s, the company removed its signature packaging and caramel colouring to ship ‘White Coke’ to the Soviet Union, and when the Berlin Wall fell in November 1989, Coca-Cola employees passed out six-packs of the drink to East Germans. Coke may be globally ubiquitous, but it is always first and foremost an American product, both as symbol and substance. A product of the union between America and the consumer capitalist economy — as the art of Andy Warhol, keen-eyed observer of American postwar materialism and fairly obsessive about coke bottles, might suggest.

America’s online prominence can be seen as a kind of cultural hegemony, a term developed by Marxist theorist Antonio Gramsci to refer to the dominance of a diverse society by a particular culture. According to Gramsci, the re/shaping of intellectual life, religion, education, language, and folklore by the ruling classes worked to form a kind of domination based on ‘consent’ rather than ‘force’, in which the worldview of the ruling group becomes the accepted and unquestionable cultural norm. Gramsci was referring to the operations of the ruling class in capitalist societies, but these mechanisms are also at work on the internet today. Americanisation online does not merely reveal the superiority of American digital products from Hollywood to Silicon Valley, nor is it a mere accident of demography. It is its own kind of soft power in the service of hegemony, one which has shaped the face of the internet and the cultures which flourish there, and which is involved in the effort to legitimise American imperialism across the globe. If America’s manifest destiny has always been to expand and conquer new territories, then what is the online realm but another frontier, waiting to be settled?

Recently I’ve been drawn to the work of William Eggleston, an American photographer working in the latter half of the twentieth-century. Eggleston is best known for his use of brightly saturated colour, a controversial contrast to the predominantly black and white art photography of his time but an innovation which enabled him to capture the scorching heat and vivid colours of quotidian life in the American South. Glossy 1970s cars roll past MacDonald’s drive-thrus; a gleaming drink is illuminated by the sun cascading through an airplane window. A man in a cowboy hat drives through an arid landscape, his windscreen caked with dust and hands gesticulating above the wheel. The inside of a motel room or the checked tablecloth of a diner; a girl splayed out on dry grass at golden hour, her hair the colour of the sun; the ubiquitous Coca-Cola sign silhouetted bright as a warning against a purple twilit sky. They’re simple compositions, but there’s depth to them, a sense of space and narrative which leads the viewer to wonder exactly who and what it is they’re observing, though the landscape is always all-American.

I know it shaped me, growing up amidst the Americanisation of everything. I may have never lived in the USA, nor visited for longer than a week, but I can name more American Presidents than British Prime Ministers, can confidently opine on the difference between particular fast food joints (Olive Garden does breadsticks and Hooters does tits?), and know more about certain New York neighbourhoods than I’ve ever needed or wanted to. I didn’t choose to acquire this information; it happened by osmosis. I imagine this is a pretty common experience for anyone existing on the internet, particularly the English-language internet, across the world. Yet looking at Eggleston’s photographs has led me to reflect in particular on the influence the American aesthetic exerted on my expectations of youth and adulthood. It’s a commonplace among Brits of my generation that a collective childhood obsession with High School Musical planted false expectations for what secondary school would be like, but the sense that I was missing out persisted all through my teenage years. From the glass coke bottles I longed for as a kid to the high school movies I watched and music I listened to as a teen (prom! pool parties! 4th of July!), and the sorority rush videos flooding my feeds today, American culture has continually shaped my idea of what youth was and should be.

Eggleston’s art is pure Americana, the sort of aesthetic which dominated my online cultural world as a teenager, despite being far removed from the day-to-day realities of my own life. I watched and rewatched music videos for songs by Troye Sivan, Hayley Kiyoko, Vampire Weekend, and Halsey, imagining a suburban life of cycling to and from my friends’ houses and driving to the beach, visiting drive-thru diners and eating soft serve ice cream like a Lana Del Rey heroine, lazing through a perpetual halcyon stretch of summer which never materialised in the UK. I’d scroll through images on Pinterest and Tumblr taken by girls my age but reminiscent of Eggleston’s saturated and deceptively simple snapshots: diner signs, neon lights, basketball courts and empty bleachers, girls splayed out and sighing in the grass. Sometimes I’d go sit on the swings in my local playground and pretend that was my life, an American life, one which (I was sure) would be far more interesting than my dull existence across the pond. The grass, as they say, is always greener. The sky is certainly bluer.

I blindly accepted this cultural output as the standard for living, and because of this, failed to look for media and art which more accurately represented my own experiences of youth. To be young, it seemed, was to be American, or so my musical diet of Lana Del Rey would have me believe. I could have looked harder, perhaps, but I was happy to be spoonfed Americana, and when I happened upon media which resonated with my own life experiences as a British teenager — Alice Oseman’s novels Solitaire and Radio Silence, or the music of Florence and the Machine — I would notice how different it felt to everything else, how much closer it came to my heart and how much sharper it struck me there. If it was hard for me to escape this dominant aesthetic, as a white Western English speaker and a cisgender woman, I can only imagine how difficult it is for those from marginalised backgrounds or cultures ignored by the pop culture industry to find true representation. Indeed, even though marginalised communities have fundamentally shaped the face of the internet, these contributions are rarely recognised or celebrated, as in the case of AAVE and Drag slang, repeatedly swallowed by the digital machine and spat out as ‘internet’ or ‘Gen-Z’ slang.

So much of America’s power derives from its image, what we would now call its ‘aesthetic’. Peaches and cream, apple pie, coke bottles, fireworks, cheerleaders and stadium bleachers, the Empire State Building, red painted barns against azure skies, cowboys, cars. The scenes photographed by Eggleston in the 1970s are instantly recognisable to everyone, even if we’ve never seen them ourselves. They’re powerfully, globally familiar, like the MacDonalds arches or a Coca-Cola bottle, and their familiarity is depoliticising. The power of the aesthetic is such that that even images of resistance to American hegemony are eventually incorporated within the centre — like the image of the Little Rock Nine walking calmly past a mob of screaming white women to their newly desegregated high school, or of artist David Wojnarowicz at an ACT-UP protest, in a jacket which reads ‘IF I DIE OF AIDS FORGET BURIAL - JUST DROP MY BODY ON THE STEPS OF THE FDA’. Past protest movements, from the Revolution to the Civil Rights Movement, have been incorporated into America’s national mythology and the stable, powerful, and ‘progressive’ image it projects to the world, even as today’s protestors face state and police violence on the streets.

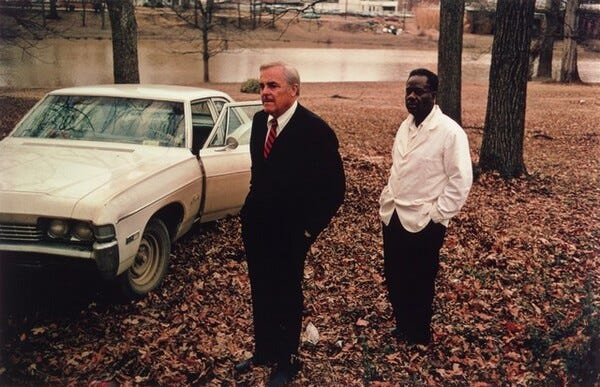

Like the American aesthetic, with its quotidian depictions of daily life and the middle-class consumer marketplace, Eggleston’s art, which strives towards objectivity in capturing its subjects, has been called ‘democratic’. There is a democracy to the images, but it is a peculiarly American kind, in which distinctions of race, class, and gender are amplified even as they are subsumed into homogeneity. In one image, Sumner, Mississippi, Cassidy Bayou in Background, a Black man in uniform stands a few paces behind a suited white man, a white car in the background. The two men’s postures exactly mimic one another, but as critic Brian Dillon writes: ‘Staples [the Black man, a family employee referred to as ‘boy’ by the artist] is smaller and stranded, has more to do with the dark trees, despite his white uniform. The whole is a study in connection, identification, hierarchy and disparity, and it is filled with reminders of race and class, however much Eggleston might like us to think of it in purely formal terms’.1 Sumner, it is worth noting, was the site of the 1955 trial of two men for the murder of the fourteen-year old Emmett Till.

As the tensions within Eggleston’s art suggest, the peaches-n-cream Americana aesthetic which dominates online imagery is also unrepresentative of many diverse American experiences and uncomfortable histories. But the dominance and visual power of this aesthetic is not unlike the American Dream itself — a story told by America to itself and to the world, a way for it to mythologise and thus legitimise itself and its actions across the globe, a form of soft power.

Today’s global youth are growing up online even more so than I did. Online soft power is therefore the perfect propaganda, ensuring the aesthetic expression of a particular ideology is so ubiquitous as to be normalised and thus unquestionable. To be so exposed to a particular culture at a time when your brain is still developing has an influence on your dreams and desires as you enter adulthood. And what is the American Dream really but a dream of individual advancement, of seizing opportunities and staking a claim, of constant advancement through the accumulation of material goods, of the pursuit of personal success and achievement at the expense of the wider community. A manifest destiny to stake a claim. How much of what the internet has become — avaricious, individualistic, and driven by profit; dominated by venture capitalists and ‘disruptor’ entrepreneurs like Musk; communities siloed off into algorithmically filtered echo chambers which constantly feed us content designed to make us the most extreme versions of ourselves — reflects the dark side of the American Dream as it has been applied to the online world? And how many of its assumptions — that we all want status and success, our individual fifteen minutes of fame, or atomised nuclear family units with access to privatised leisure and security, rather than long-lasting communities and tangible connections — have filtered into the core ethos of the Internet? The ‘trad’ movement is just the latest and most explicitly right-wing manifestation of this Americana idealisation, as the recent discourse over that Ballerina Farm article might suggest.

Change has been brewing in recent years. America’s digital cultural hegemony has been challenged, as the ongoing debates in the West over Chinese corporations TikTok and Shein suggests (China also operates its own internet). According to Fatima Bhutto, author of New Kings of the World: Dispatches from Bollywood, Dizi, and K-Pop, a new era of global cultural influence is dawning, as ‘pop culture being produced out of India, Turkey and South Korea – to say nothing of China, which is a separate story altogether – exposes the twentieth century Western cultural tsunami as receding and revealing the seashore’.

This change should be celebrated as a sign of a more diverse, vibrant, and representative global pop culture. But we should also be wary of replacing one hegemony with another, or allowing state-sponsored monopolies and political agendas from across the globe to dominate our precious internet spaces. American celebrities may sign bombs on TikTok, but Israeli soldiers post GRWM videos from bombed-out Palestine, whilst extremist groups from across the globe use social media to spread propaganda and misinformation. And the more we participate in the online world, sharing our faces, bodies, lives, the more that participation can be manipulated for corporate and political gain as our data is parcelled up and sold for a profit. ‘Welcome to the Age of Digital Imperialism’, headlined the New York Times in 2015, citing Facebook, now Meta’s, evangelising ‘social mission’ about the power of sharing and using user data. A decade on, the situation only looks worse.

I now find it vaguely irritating, how inescapable the U.S. is on my social media feeds. Ultimately, though, I can block a few accounts, mute a few buzzwords, follow different people and change the shape of my internet bubble for a while. But the issue runs deeper than what we see on the surface of the internet. Soft power has seeped into every aspect of our online existences. Big corporations buy and sell our data, states and companies use it to further their own agendas, in a new form of the ‘coca-colonisation’ alliance between capitalism and modern imperial power. With our attention spans for sale, we are easily distracted by aesthetic propaganda whilst atrocities are committed in the real world, and quickly shrug off the acts of tech tycoons like Musk and Bezos, who see the internet as their kingdom and us as their vassals. Even on a physical level, most of the internet’s infrastructure is based in the U.S., and the ten largest internet companies are split evenly between the U.S. and China.

The American digital hegemony is very real, and it isn’t sweet like apple pie. To misquote John F. Kennedy, a U.S. President who intimately understood the power of pop culture and the media, in the online age ‘we are all Americans’. We are all Americans — whether we like it or not.

As always, thank you for supporting my writing. I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments and Notes.

twenty-first century demoniac is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. You can now also make a one-off donation through Buy Me A Coffee.

Brian Dillon, Affinities, p200

is it interesting or uninteresting for you to know that inside the U.S. we have this micro-dynamic between the rest of the country and california, or sometimes california + new york vs the rest of the country? where in every other state people feel underrepresented and like these big ultra populated areas are sucking the air out of the cultural room. thinking about visiting family friends in ireland when i was 18 and my irish friend my age complained about this exact same thing to us, it was during the 2016 election too so she had the same points about political discourse then. its all so fair and would probably annoy me just as bad!

such an interesting read! and so interesting to hear a non-american's perspective on americana - i grew up in a prototypical suburb with pool parties and football games and whatnot and found all of it incredibly boring, even stifling. i think that's also why i have a hard time connecting to lana del rey's music + general unchallenged interpretations of coca-colonization (and why I'm such a huge ethel cain fan!)