blunting the knives

disruption and disintegration in the life and art of David Wojnarowicz (2020 repost)

Preface

This essay was originally published Summer 2020 in the Broad Street Humanities Review, an Oxford-based student-led academic journal which appears to have gone defunct. During lockdown, I read David Wojnarowicz’s memoir, Close to the Knives, as well as the critic Olivia Laing’s writing on his work. I was captivated by his humanity in the face of sickness and brutality, even, as he wrote, ‘after lifetimes of all this’.

I’ve been thinking about Wojnarowicz again recently; I’m working tangentially in the art world, despite my limited knowledge thereof, and that proximity has raised questions for me about my own relationship to art. What draws me to an artist, what influences my choice, where does the boundary lie between aesthetic and art? Additionally, like so many of us I’ve been disturbed by the open and often violent backlash against the meagre political, social, and cultural gains queer people have made in mainstream society since Wojnarowicz’s lifetime, especially in the Anglo-American world. When I wrote this essay, I was much more open about and critically engaged with my bisexuality. Returning to Wojnarowicz, whose life and work inspired the AIDS activist organisation ACT UP, is a pertinent reminder of the necessity as much as the power of action, the role of art in activism, and the importance above all of human connection and solidarity across boundaries, borders, and identities.

recently wrote a great piece on the virtues of saving and reposting your work, which inspired me in part to return to this essay and post it here for a new audience. It was shaped by the preconceptions of 2020, and the theme of the journal it initially appeared in, ‘disruption’. I’ve made minor edits accordingly, and removed the poem which was initially enclosed with the piece, yet it still stands much as it did then.TW. Detailed discussion of death, sickness, AIDS, homophobia, and discrimination.

In 1987, the multidisciplinary artist, writer, and activist David Wojnarowicz stands beside the bed of a dying man. The man is Peter Hujar, a photographer and Wojnarowicz’s closest friend, a onetime lover he describes as ‘my brother my father my emotional link to the world[1]’. Finally, after ten months of battling against the disease which has slowly reduced his body to little more than cancer and bones, Hujar slips away. Yet Wojnarowicz, who has already lost so many to AIDS, cannot cry. Instead, he takes out his camera and points it at Hujar — at his emaciated face, eyes and mouth cracked open, at his feet, at a hand curled like a bug on the hospital bedspread. The triptych of photos are monochrome, their edges gently softened, yet there is rage in them too, in the deep shadows and the isolation of the corpse. Eventually, Wojnarowicz breaks down. ‘I’m amazed,’ he will later write, ’that we can still be capable of gestures of loving after lifetimes of all this[2].’

David Wojnarowicz’s life is both disrupted and disruption. As an openly queer, radical artist, his very existence defied the American status quo. Abused as a child, Wojnarowicz found community and acceptance in the New York City of the 1970s and 1980s, a dangerous place which nonetheless provided a vibrant, inclusive community for artists and misfits, and a thriving gay social scene. Yet with the AIDS epidemic and increasing gentrification of New York, this vibrant acceptance was agonisingly disrupted. After Hujar’s death, Wojnarowicz’s work grew more political and his activism more vocal, his art standing as a testament to a world where love and community are forever hounded into the shadows by prejudice. The two silkscreens of 1990 ‘Untitled (Act Up Diptych)’ reveal the violence lurking under the veneer of American society. The first is a map of America warped into a red and white shooting-range target, atop green and white numbers. Looking closer reveals stock market data running through the very fabric of the nation. The second is a blurred image of falling male bodies, underlaid with Wojnarowicz’s characteristic prose commentary on AIDS, America, and politics. ‘“If you want to stop AIDS shoot the queers” says the ex-governor of texas’ reads one line. In these artworks, prejudice and capitalist exploitation are shown as endemic to an American society in which minorities are dehumanised, reduced to statistics or pinned to a target.

What astounds me most about Wojnarowicz is his capacity for tenderness in the face of trauma such as this. In his essay ‘Being Queer in America’, the writer lays out a tableau of experiences, his own and others. The essay recounts his time as a rent boy fighting to stay alive on the streets, a violent assault ignored by the police, and a graphic account of his violent rape by a stranger. As with much of Wojnarowicz’s writing, it hinges on Hujar’s death from the invisible killer of AIDS — a kind of ‘connect-the-dots version of hell’ when any friend or lover could be next[3]. Despite all this pain, at the moment of Hujar’s death

‘we’re sobbing and I’m totally amazed at how quietly he dies how beautiful everything is with us holding him down on the bed on the floor fourteens stories above the earth and the light and wind scattering outside the windows[4]’.

It is a glorious sentence. Even in the midst of utmost agony and grief there is wonder at this strange, brave world, which can hold so much beauty and so much pain simultaneously — a bit like the body, abstracted into little more than limbs on the bed, the same angle taken by the artist’s camera lens.

Run-on-sentences and jagged scene-changes such as these are characteristic of Wojnarowicz’s writing, just as warped perspectives and striking, fluid lines characterise his visual art. Deeply authentic, it’s as if both an intimate internal monologue and the collective voice of a community have been captured on paper. In ‘Being Queer in America’, he writes ‘I always tend to mythologize the people, things, landscapes I love, always wanting them to somehow extend forever through time and motion[5]’. This is the impulse of both artist and activist; to create memory, to give voice. It’s an impulse that transcends history and context — consider the impassioned, strikingly beautiful murals and memorials that have appeared across the world in connection with the protest movements of in recent years.

Love and rage are the dual themes of Wojnarowicz’s writing and art, interwoven so tightly they are inseparable. To be queer in America renders that separation impossible. Each intimate encounter is laced with fear — the looming shadow of a cop car forcing ‘the momentary disengagement from the accelerations where the mind travels in sex…[until] they can resume their rituals and rhythms[6]’. Sex is something holy, rather than something sinful, dirty.

‘Untitled, 1990-91’, a portrait of the artist as a smiling, all-American child is surrounded — one might say outnumbered — by a rainfall of newsprint-style text which conjures to mind the bars of a prison cell. ‘One day this kid will get larger’ it explains, before detailing a slew of events that will ‘make existence intolerable for this kid’ simply because, it is revealed, he is about to discover ‘he desires to place his naked body on the naked body of another boy’. The self-portrait flagrantly defies the demonisation of the gay community, showing the people — the grown-up-too-soon children — behind the shrouding veil of stigma. The final line suddenly depoliticises gay sex, returning to intimacy, desire, even love, and silently asking the viewer if all this horror can possibly be justified or if they will act now against it.

Or, as Wojnarowicz puts it in Close to the Knives, his collection of autobiographical essays:

“Some of us are born with the cross-hairs of a rifle scope printed on our backs or skulls…[the powerful] consistently abstract human life and treat minorities as nothing more than clay pigeons at a skeet-shooting range[7]”.

Here again is the abstraction of humanity, this time by the violence society perpetuates in both its overt and its covert, dehumanising forms. Recalling the target of ‘Untitled (Act Up Diptych)’, Wojnarowicz’s writing is as visceral as his art. It hurts to read these lines — not just because of the historic pain, but the current pain it evokes, for those with targets still plastered on their backs. Wojnarowicz cared deeply for the plight of all minorities, not just the gay community, championing the value of diversity and inclusion against the oppression of what he called the ‘ONE TRIBE NATION[8]’.

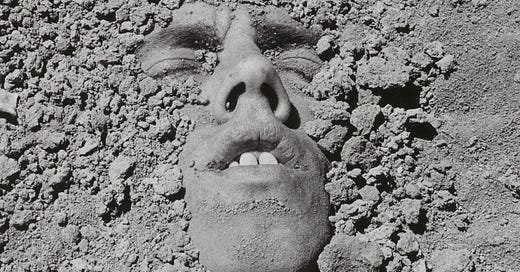

The interplay between light and darkness, shadow and form, runs throughout Wojnarowicz’s work. The subjects of his black and white photographs face away or are interrupted by physical matter, as in ‘Untitled (Face in Dirt), 1991’ where grave rubble shrouds the artist’s own face. In ‘Something from Sleep III (For Tom Rauffenbart), 1989’, Wojnarowicz’s partner stares down a microscope, his body made up of stars and planets. Here too is a fascination with the body in relation to its environment — the figure filled (perhaps figuratively as well as physically) with an open expanse of space, the self splintered into stars. We are all stardust, the images say, and ashes to ashes, dust to dust. Perhaps these motifs derive from the need to hide, to conceal one’s identity from the world’s cruel gaze. There is licence in darkness, but there is also fear and erasure. I am reminded of the swimming pool paintings of David Hockney, another gay male artist working against social stigma — the bodies distorted by water, the faces turned away. Celebration and concealment entwined together.

‘Losing the Form in Darkness’, an essay on the Chelsea Piers, then an established meeting-place for gay men, ends with a surreal dream-sequence evoking the derelict cruising site with heightened reverence, calling up the archaic grandeur of marbled heroes frozen in ‘the eternal sleep of statues’ and ‘beneath the sands of the desert’[9]’. These ancient monuments mirror the bodies of the vilified in their makeshift haven, the ephemerality of their crude, zoomorphic graffiti. As in his photos of Hujar, Wojnarowicz shuns stigma and honours these stories, reminding us that society still does not memorialise the 32.7 million and growing victims of the worldwide AIDS epidemic, nor those slaughtered in homophobic hate crimes.

Wojnarowicz as artist and writer played with the idea of posterity, of the question of selfhood and artistic authenticity, opening up a conversation about his own artistic afterlife. One of his most famous works is the series ‘Arthur Rimbaud in New York’, which placed models wearing a quizzical, aloof mask of the poet in assorted New York scenes — in Times Square, on the subway, smoking in a derelict house. There is something whimsical, delightful in the artworks, but there is also something darker. In one, Rimbaud bleeds out in a puddle of his own blood, a gun fallen from his fingers. Blank paper eyes stare at the camera. A deep sense of isolation courses through the images, and they force us to ask ourselves questions about the role of the individual in the city. Is the subject buyer or bought? Reveller or rioter? Peripatetic or simply lost? Famous or anonymous? Is the model intended to be Rimbaud, or is it simply what it is — a mask? The photos are taken in places which no longer exist in the form Wojnarowicz saw them, gritty underground urban locations soon to be cleaned up and swiftly gentrified. Like the other artists of the 1980s East Village scene including Nan Goldin, Keith Haring, and Jean-Michel Basquiat, in the Rimbaud series Wojnarowicz captures a lifestyle on the brink of disappearing.

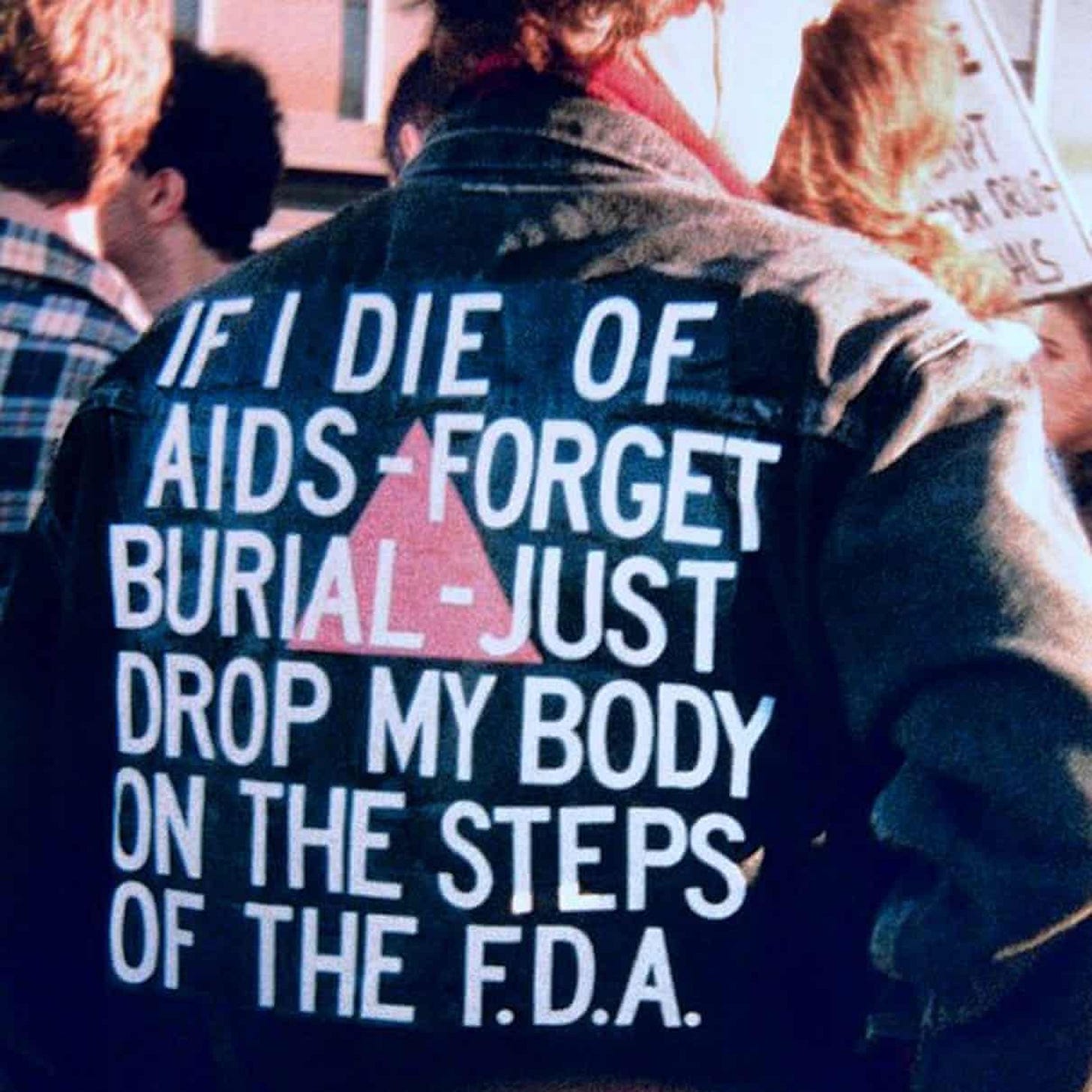

Wojnarowicz’s work is as vital today as in the 1980s. But art is polyphonic, our interpretations shaped by the age we live in, the person we are. Shapes cast strange shadows from different angles; perception is a broken mirror. Though his art and life are not well known, many may be subconsciously aware of Wojnarowicz — perhaps having seen his cover for the U2 single ‘One’, or the grainy photo of a lanky activist from behind, denim jacket emblazoned with ‘IF I DIE OF AIDS FORGET BURIAL - JUST DROP MY BODY ON THE STEPS OF THE FDA’. The FDA is the Food and Drug Administration, responsible for the US government’s HIV/AIDS research yet stymied by Reaganomics budget cuts and corporate interests, was the subject of activist ire culminating in ACT UP’s 1988 Seize Control of the FDA Action[10].

I find the facelessness of this candid as striking as the masked Rimbaud images — it is not individual, but generalised. It is man as furious yet ironic activist, a symbol of controversy, a subject of prejudice and of power, rather than damaged child, gentle lover, or mourning friend. It is man forced by the actions of the State to stand against the State, from the discovery of his unsanctioned desires chronicled in ‘Untitled, 1990-91’ and on into the struggle of the plague years. It is also man identified as queer but without individual identity. Like the broken glass Wojnarowicz often references, identity and community are unfixed and fluid, especially in the face of discrimination, violence, or sickness. Close to the Knives is a ‘Memoir of Disintegration’, because it is patch-worked together from jagged pieces like a broken window, or the AIDS Memorial Quilt, but also because of the disrupted life it recalls: the transient pleasures, the piercings of pain, the dissolving of community, the dehumanising violence of so-called morality. It is a cruel irony that AIDS breaks down the body, literally abstracting humanity through cancerous growths, the loss of limbs, of muscle and fat. The disease makes living corpses, finishing the work begun by society.

Yet posterity is never fixed, especially in matters of art and history, charged as they are with interpretation. Looking back can shed light on the present; only in 2010 did the Catholic League attempt to censor Wojnarowicz’s short film A Fire In My Belly[11]. Progress towards equality and inclusivity is anything but linear. Under President Trump, the gains of the LGBT community have been rapidly countered, with GLAAD reporting in 2016 that ‘minutes after Donald Trump was sworn into office, any mention of the LGBTQ community was erased from White House, Department of State, and Department of Labor websites[12]’.

The ACT UP slogan ‘Silence = Death’ has reemerged in Black Lives Matter protests as ‘Silence = Violence’, and in recent years the student anti-gun movement has adapted Wojnarowicz’s slogan: ‘If I die in a school shooting, drop my body on the steps of the NRA’. ACT UP drew on the traditions of civil disobedience and public protest, and pioneered new tactics (Seize Control of the FDA can be seen as a direct predecessor to the Occupy Movement), but AIDS activism is rarely recognised as a driving force in twentieth century protest movements. The stigma Wojnarowicz and his fellow artist-activists sought to battle is not yet dismantled. Even a 2018 Wojnarowicz retrospective at the Whitney Museum failed to acknowledge ACT UP’s importance in both his life and the queer rights movement, and faced accusations of sanitisation and gentrification.[13]

The slogan on that famous jacket also comes from Close to the Knives. Wojnarowicz asks:

“what it would be like if, each time a lover, friend or stranger died of this disease, their friends, lovers or neighbors would take the dead body and drive with it in a car a hundred miles an hour to Washington DC and blast through the gates of the White House and come to a screeching halt before the entrance and dump their lifeless form on the front steps.”[14]

A year after writing these words, he himself would die of AIDS, one domino in a long line of many toppled over by decades of governmental neglect and social stigma.

In 1996, Wojnarowicz’s ashes, along with those of hundreds of other AIDS victims, were scattered on the White House lawn in a gesture of mass defiance[15]. Directly inspired by his words, the two ACT UP Ashes Actions were an outpouring of public grief and a deeply political mass funeral; a community telling the world they wouldn’t be ignored anymore, and a way of giving the silenced dead a voice. A way of making the abstract concrete once again. The artist’s disintegrated body becoming the art, the protestor becoming the protest, in David Wojnarowicz’s final act of disruption.

Further Reading

David Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration (2017 edition)

Olivia Laing, The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone (2017)

[1] David Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration (Edinburgh, Canongate, 2017), p. 112

[2] Close to the Knives, p. 117

[3] Close to the Knives, p. 75

[4] Close to the Knives, p. 91

[5] Close to the Knives, p. 88

[6] Close to the Knives, p. 64

[7] Close to the Knives, p. 66

[8] Close to the Knives, p. 161

[9] Close to the Knives, p. 30

[10] https://actupny.org/documents/FDAhandbook1.html

[11] https://cs.nyu.edu/ArtistArchives/KnowledgeBase/index.php?title=A_Fire_in_My_Belly_Controversy

[12] https://www.glaad.org/tap/donald-trump

[13] https://www.frieze.com/article/why-has-whitney-tried-sanitize-david-wojnarowicz

[14] Close to the Knives, p. 131

[15] https://actupny.org/diva/synAshes.html