Towards the end of every year my dad types out an A3 letter in 13pt Comic Sans font, prints a double dozen and slips them into his Christmas cards. As long as I can remember — as long as I’ve lived — the format has remained the same. A few wry lines reviewing his year plus a handful of family photos. These were once semi-artful posed portraits, now iPhone snaps I diligently help compile for him. This year, one of the photos was of my DPhil Matriculation, an archaic ceremony my university holds for incoming students. If you already have a degree from the university you’re not technically meant to attend, but no one checks names on the door, and it’s as good a way to skip the library as anything.

I compared this photo to one from five years ago, from the first week of my undergrad degree. In the earlier photo, I look wary behind thick dark glasses and I’m smiling, but only with half my mouth. Maybe I’m already incubating the throat infection which will throw off the rest of my term, or maybe I’m gritting my teeth. My hair is cut in a too-short bob that suggested 1920s flapper on good days and Princes in the Tower on bad. I’d left my hairdryer at home, so it was still wet, and a little greasy, because I was using all natural shampoo on the Curly Girl Method. My collar is wonky.

In the more recent photo my collar is still wonky and my now too-long hair is still a mess but my manner is different. I have pierced ears now, for one, and I’m heavier, and my glasses don’t hide my eyes. My shoulders (alas also still wonky) are back and my chin is raised. I look almost like someone who moves confidently through the world. I look like an adult. There’s only a suggestion of the girl I was when I first moved to this city, the first place I ever really felt at home.

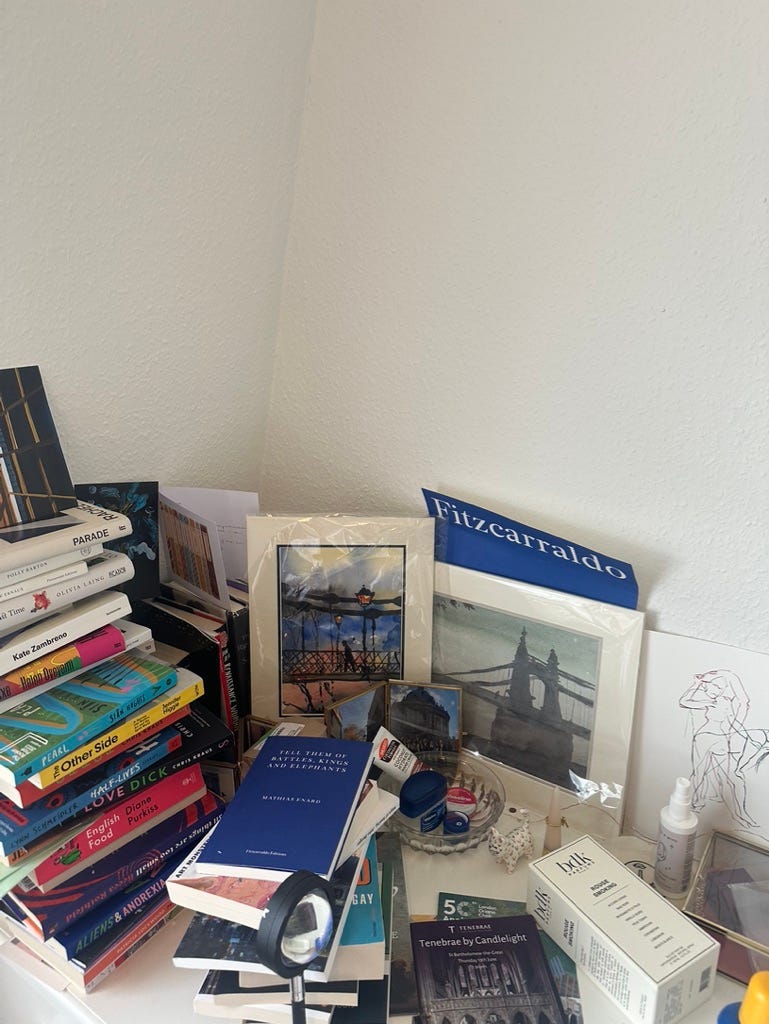

I noted something similar in my journal recently, having come to the end of my latest Moleskine just a week before the New Year. It would have been nice to start fresh in 2025, but I couldn’t survive seven days sans gratuitous self-exposure, so I trudged off to buy myself yet another £23.50 notebook (couldn’t my 15-year-old self have chosen a less pricy medium?). This would be my fourteenth since I started journalling regularly nine years ago. Stacked like dominoes at the top of my bookshelf, they’re somber soldiers in their black leather jackets, in contrast to a riotous bouquet of programmes and exhibition guides. Some warp and bulge, stuffed with ticket stubs and other ephemera, or, in one notable case, evidence of ex-best friends, others are slender and neat, sparsely filled. They smell of wood chips and new car seats and candle wax. They contain over a third of my life.

Who was the girl who wrote those first words, who posed for that earlier matriculation photo? She is both wholly continuous with me — in fact, I am entirely dependent upon her for my ongoing existence, for the person I am today — and deeply other. She’s me but she’s not me. Even when I reread her words, I can’t get inside her head. In some ways I’m outrunning her, I wrote in my new journal. In other ways I will always be searching for her.

I’ve grown up a lot this year. Not just physically, though there’s certainly that. I’ve worked and left my first ‘adult’ job. I’ve travelled alone for the first time. I got my PhD, my funding, my first commissions for writing, whilst this blog grew in a way I’d never expected to happen. I’ve made more friends in the last twelve months than I did in my whole teenage years. I moved back to Oxford. I officially entered my mid-twenties. And all the while time kept dancing onwards, sometimes as regular as a double-time frog-march, sometimes leap-frogging haphazardly, swallowing the summer in a sprawl-legged gulp and spitting me out in October, caught short.

I used to write a regular seasonal round-up, but I don’t particularly like doing that sort of post anymore, especially as my following has grown. It makes me feel like a YouTuber filming a Chatty GRWM, or, if I am being honest, like the sort of blogger I really don’t want to be, spilling my guts out into a digital sewer, and for what exactly? The personal essay is on my 2025 outs list for a reason. At the same time my roots are firmly embedded in that mid-2010s confessional, Tumblr’s anonymous Ask box. And I do like treating this blog as, well, a blog. So this is my year in books — specifically, a handful of books I noted down sections from in my journals and notebooks, for whatever reason.1 At the end of a year filled with reading and thinking about reading, what better way to look back than to take my notebooks down from the top of the shelf and remind myself what struck me, when, and why. As a drunken note I wrote to myself at some point this year reads, ‘All I want to do is read I feel about reading like I do about sex (Ok having had sex 5 hours later I do not entirely agree with the above sentiment)’. So true, girl.

Notes on notes on 2024

March — I Love Dick by Chris Kraus

‘Everything is filtered through her death…Let a girl choose death — Janis Joplin, Simone Weil — and death becomes her definition, the outcome of her ‘problem’. To be female means being wrapped within the purely physiological. No matter how dispassionate or large a vision of the world a woman formulates, where it includes her own experience and emotion, the telescope is turned back on her. Because emotion’s just so terrifying the world refuses to believe that it can be pursued as discipline, as form… I want to make the world more interesting than my problems. Therefore I have to make my problems social.’

I noted this passage at the start of the pocket notebook I took to Vienna. There’s a sticker for the Sigmund Freud museum at the bottom of the page and a bracketed note which reads ‘[Egon Schiele - the inexplicable agony of existing in a body]’. In Vienna we read a lot and ate a lot and had a lot of sex and visited a gratuitous number of museums. B. called seeing The Kiss a religious experience and proceeded to hold me like that for the rest of the trip, but I mainly remember glaring at the woman taking selfies in front of Klimt’s glistening masterpiece. For those four days like the painting I was incandescent with something, I felt lit from within and preternaturally healthy, like the unseasonal heat, 17C in mid-March, in a place we’d been warned was freezing. I could live here, I kept saying, we should live here, and a few months later when B. mentioned a job posting in the city I secretly longed for him to apply.

Part of that incandescence came from this book, I think. I Love Dick first came out in 1997, but reading it in 2024 it still felt incendiary, crackling with new ideas, new forms, new ways of receiving and translating the world. Here were ways to be at once a woman, a girl, a reader, a writer, an artist, a lover, ways I’d never dreamed of before. Ways to harness emotion ‘as discipline, as form’. Ways of undermining the phallocentric ways of making meaning in both sex and letters, a deadly serious form of play, like Chris’s letters to the eponymous Dick.

This passage, and another about handling female ‘vulnerability like philosophy, at some remove’ reminded me of Francesca Woodman, my favourite artist, who was the co-subject of the National Portrait Gallery’s Portraits to Dream In exhibition this spring. I liked the exhibition, because it freed Woodman from the usual story about her art and life — that of the tortured young woman who killed herself before her prime, and whose work can only be read through such a funereal lens — ‘death becomes her definition’. I thought and read and wrote a lot this year about the situation of the female artist or writer, who must work both with and against the condition of her gender. Kate Zambreno’s Heroines, Rachel Cusk’s Parade (see below), Lauren Elkin’s Art Monsters and Scaffolding, and Deborah Levy’s August Blue were points on this map, as were Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, which I read across 2024, and Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, which I revisited for this essay in Atmospheric Quarterly. Kraus's work was one of the starting points for that project; I referenced her in my essay ‘in search of cool: who is the literary it-girl and why should we care?’, the piece which dragged me into two months worth of boring internet controversy but which convinced me of the value of continuing to analyse apparently innocuous trends in more critical depth. It also introduced many of you to this blog; I have I Love Dick to thank for that.

I keep trying to find a way to describe reading I Love Dick which isn’t a sexual metaphor, but I can’t. In fact, there’s another passage copied a few pages later which puts into words the sensation I’m failing to. I think I was sitting in Vienna Airport when I wrote it. ‘Reading delivers on the promise that sex raises but hardly ever can fulfil — getting larger ‘cause you’re entering another person’s language, cadence, heart, and mind.’ That’s exactly how I felt, too.

June — Parade by Rachel Cusk

‘Once, she was in his studio for the visit of a female novelist, who was struck as though by lightning by the upside-down paintings, much as G’s wife had been herself. I want to write upside down, the woman exclaimed, with considerable emotion. No double G found this a preposterous thing to say, but G’s wife sat there satisfied, because she herself felt that this reality G had so brilliantly elucidated, identical to its companion reality in every particular but for the complete inversion of its moral force, was the closest thing she had come to the mystery and tragedy of her own sex.’

I’m cheating here, because I didn’t actually copy any passages from Parade into my battered notebook. Instead, I made notes on Cusk’s Yale Review interview with Merve Emre, from March, and an in-conversation I attended at Union Chapel, Islington, with S., a new friend, in June. Going back through the book, which is bisected from a half-finished reread, begun almost as soon as I’d finished it the first time, I note an increasingly-frenetic number of dog-eared pages, but struggle to find the passage I’m searching for. I’m sorry I’ve ruined it! I said to Cusk, handing the book over to be signed. I know some authors hate that! By the way you’ve had the greatest influence on me. She smiled uncomfortably; S. and I left with the sense we’d somehow insulted her.

There are a number of ‘G’s in Parade, most of them based off real artists. Like Ali Smith, whose Gliff I also enjoyed this year, Cusk writes wonderfully about art and its effects on people. Of Louise Bourgeois, another ‘G’, she writes cooly, cleanly, that ‘Art, rooted in insanity, transforms itself through process into sanity: it is matter, the body, that is insane’. At the start of the book, the ‘G’ in question is Georg Baselitz, who ‘believed that woman could not be artists’. The narrator is his wife, who creates the ‘conditions for the obliviousness of [his] creating’ whilst feeling that he has accidentally captured something essential about the female condition in his upside down paintings, something set-apart, inverted, a mundane madness. This story runs aside one from Cusk’s own life, in which a stranger punched her in the street, a senseless yet premeditated act of violence which shakes her to the core, and which she connects with other physical experiences of femininity, such as childbirth.

This passage, from the Baselitz section, immediately struck me. What would it mean to write upside down? If possible, would it be a particularly female form of writing, as Cusk seems to think? I think writing upside down lies at the core of Cusk’s project, which looks beyond language and narrative and character to the body, and seeks to bring the written word closer to the image, in service of a uniquely female project of creation. After childbirth, ‘narrative becomes repellent’, Cusk said in the talk I attended at Union Chapel, and in her Yale Review essay that ‘it seemed like the pre-formation of language was far more insidious than I had thought it to be’. This sense that narrative is a falsity, a violent one which papers over the raw conditions of reality, particularly for women, pervades Cusk’s work. One of my favourite essays of hers is ‘Driving as Metaphor’, from the collection Coventry, and also available on the NYT. In it, the incursion of reality into narrative comes when Cusk is driving along a foreign motorway in a hire car: dazed by the unknown layout, ‘it was as if driving was a story I had suddenly stopped believing in, and without that belief I was being overwhelmed by the horror of reality’. Back home, she witnesses the aftermath of a car-crash. This sudden ‘horror of reality’ reminded me of Clarice Lispector’s The Passion According to G.H., which I had read a couple of months earlier, back in Vienna, a book I would be reminded of again in October, when a man in front of me on the stairs ground a large black spider to graphite under his heel.

In Parade, narrative ‘reality’ is punctured by the act of random violence in the street, and a suicide in an art gallery, which leads the gallery’s director to reflect that ‘the violence of what happened…which in an instant destroyed all these arrangements, seemed both pointless in itself, and also to give an impression of our work and our values as pointless, that they could so easily be swept away’. Like the loss of belief on the motorway, these moments of puncture gesture at the limits of the language and narrative which structure our social worlds, and return us to the body, whose ‘stuntman’ has been caught unawares. They turn us upside down; as Cusk reflected at Union Chapel, they provoke a ‘crisis of form’ in our ‘lived experience’. It is ‘meaninglessness as meaning’ which leads back to the body.

I was fascinated by the idea of ‘writing upside down’. E. and I held a workshop on the topic on a sweltering summer evening in a Bloomsbury bar. Over rosé and pints, we discussed how one might do this. Literally flip the letters over, I suggested, or use your non-dominant hand. Embrace a kind of Spiritualist/Surrealist automatic writing. Return quite literally to the raw material of the body, its total, pre-linguistic physicality. As usual, Cusk’s clarity of language belies the complexity of her meaning. I still don’t understand all of Parade. I don’t know if I agree with all of it, if ‘agreement’ is the way you should approach such a text. It’s the sort of book I want to pick up and reread parts of throughout my life, perhaps next when Bourgeois’s spider returns to the Tate Modern in May, or when I have children myself. But like all of Cusk’s work, it temporarily turned my world on its head.

September — Intermezzo by Sally Rooney

‘Aesthetic nullity of contemporary political movements in general. Related to, or just coterminous with, the almost instantaneous corporate capture of emergent visual styles. Everything beautiful immediately recycled as advertising. Sense that nothing can mean anything anymore, aesthetically. The freedom of that, or not. The necessity of an ecological aesthetics, or not. We need an erotics of environmentalism. Stupidly making each other laugh.’

I said at the start of this post that it was by no means a comprehensive list of 2024’s best or most influential books. Yet any reading year in review would be amiss without the new Sally Rooney, which arrived in early September amidst much fanfare and a flurry of tote bags, despite the author’s evident discomfort with what I can only call marketing guff (‘Everything beautiful immediately recycled as advertising’!). I wrote an entire essay about Intermezzo and Sally Rooney’s Southbank in-conversation (once again with Merve Emre, who seemed to get everywhere this year) so I’ll be brief here. Intermezzo is great. Whilst echoing some of Rooney’s earlier preoccupations and archetypes — Dublin, academia, the intersections between class and gender, debate, miscommunication between lovers and friends, to name but a few — the novel feels more mature, a developed yet freshly experimental voice.

Mid-September was a good period for reading: I finally finished The Second Sex, and came to reading Intermezzo straight off the back of Anna Karenina (another favourite from this year, which made me sob in a Marylebone coffee shop whilst an Italian man on an important business call glared and nudged my legs) and Simone Weil’s The Need for Roots, with its exhalation of communal rootedness and mutual obligation. So I felt primed for both the novel’s attentive portrayal of character, and its richly political exploration of ‘the demands of other people’, the social, romantic, familial, and economic ties that bind us together, including even the needs of a childhood dog.

I’ve selected this passage because it captures something of the milieu Rooney is evoking — highly educated young-ish people with lots of ideas but not a whole lot of practical politics2 — as well as the effortless way in which she writes relationships. The back-and-forth riffing, the two voices becoming one, the juxtaposition of serious political conversation and ‘stupid’ laughter. Short sharp sentences which could save the world, if they could get out of bed for long enough. Rooney gestures at the political through the personal, something she’s been criticised for, but which I think is the core of her brilliance. A relationship can contain the whole world, but that includes the world’s failures, its missteps, its inequalities. In Intermezzo, Rooney is particularly concerned with the relationship between intellectual and sensual desires and ways of relating to one another. Through Peter and Sylvia’s relationship, captured here, Rooney explores what words can do, how love can be a shared life of the mind, but also how easily words can puncture that illusion and cause real injury. I wasn’t enamoured with Peter’s happy ending, how he gets to have both Sylvia and Naomi, his loves of mind and body, but I do like how through the ménage à trois Rooney indicates that all relationships are complex networks of negotiation and obligation, no matter how many parties they contain and in what configuration. If two brothers can heal their rifts, if three lovers can, perhaps we all can. If society is suffering from the ‘aesthetic nullity of contemporary political movements in general’, then maybe the answer to our issues lies in love?

A couple of months after reading Intermezzo I caught myself stalking around Radcliffe Square, trailing scarves and listening to B. complain over the phone about some chess tournament he’d lost at the last moment. I was cold, and late for an evening lecture on the history of death, and I suddenly thought to myself: Fuck, I’m in a Sally Rooney novel. We’re all just normal people.

October — Immaculate Forms: Uncovering the History of Women’s Bodies by Helen King

‘We exist as bodies in history; but history is not impartial, and it does not stand back and watch. It tells us not just stories of bodies, but how to read our bodies.’

As Kraus writes in the passage from I Love Dick quoted above: ‘To be female means being wrapped within the purely physiological.’ Part of my interest as a historian of the body is exploring the roots of this association, bound so tightly it stifles, between women and the physical, the worldly, the flesh. It was the work of historian and classicist Helen King which first led me to my Masters research project on early modern women’s pica, and which set me on the path to the PhD I’m now pursuing.

King’s new book, the magisterial Immaculate Forms, explores four body parts which have at varying times and to varying degrees been considered to ‘make up’ a woman — the breasts, the hymen, the clitoris, and the womb. The question of what makes a woman is one with contemporary resonance, and in historicising it King draws attention to the construction of the body across time, as well as how ‘female’ has never been a fixed category. She problematises many of the bio-essentialist assumptions about the body which continue to hold sway today, particularly in anti-feminist and trans-exclusive circles. Immaculate Forms is a vital antidote to these assumptions, a weapon against those who have exploited the idea of the ‘biological human female’ for reactionary and violent ends.

Because I was reviewing Immaculate Forms for an open access historical review journal, I read it closely, and made rough notes on the text in its margins and a pocket notebook printed with pressed flowers.3 This is very different to the way I usually approach secondary historical literature, as a source. Since starting my PhD in October, it’s been both interesting and challenging to pursue multiple intellectual projects at the same time. Sometimes I feel like Bilbo’s line from The Lord of the Rings — like ‘butter scraped over too much bread’. I’ve never really given up on wanting to be a Renaissance (Wo)Man, like the playwright-poet-polemicist-physicians I encounter in my research. I’m anti-disciplinary, I said to the friend of a friend at the pub. I want to do everything. But am I trying to do everything, and failing to do anything? My historical research which I’m being paid to do, this blog, my other research projects, commissions and pitches seeking to better establish myself in the ‘literary sphere’, the opportunities I’ve said an enthusiastic yes to then found shunted to the back of my mind. I want to write fiction, too, but something has to give. Jack of all trades, master of none? Reading King, who has had a rich, interdisciplinary career, and whose interests range from archaic votive vessels to knitted womb plushies, Marian nursing imagery to ‘breast is best’ campaigns, I felt weirdly reassured. Those gracefully made, insightful connections across time and space are what make Immaculate Forms such a compelling, as well as such a timely, read. Not everything has to be hyper-specialised. There’s space for both high and low, old and new — perhaps, say, someone who can talk about the mechanics of premodern digestion and Instagram food porn, Renaissance dieting and modern orthorexia.4

I’ve managed to turn my discussion of King into a discussion of myself. Personal essay near a book review, or however that viral tweet about the LRB goes. But I would highly recommend Immaculate Forms to everyone interested in the way sex and gender operate, and have operated, in Western society. As King writes in her conclusion, history is in no way ‘impartial’ when it comes to both medical-cultural discourses and our lived experiences of the body. History ‘tells us not just stories of bodies, but how to read our bodies.’5

December — The Use of Photography by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie

‘There is nothing of our bodies in the photos. Nothing of the love we made. The invisible scene. The pain of the invisible scene. The pain of the photography. It comes from wanting something other than what is. The boundless meaning of the photograph. A hole through which the fixed light of time, of nothingness, is perceived. Every photo is metaphysical.’

My final finished read of the year was the newly translated The Use of Photography, Annie Ernaux’s 2005 collaboration with her lover, the photographer and journalist Marc Marie. I read it over Christmas, listening to carols on the radio at home or half-watching B. play chess with his family, picking at blunt shards of chocolate. A collaborative project between Ernuax and Marie, word and image, The Use of Photography emerged organically out of the pair’s 2003-4 love affair, the period of the early Iraq War, during which Ernaux was undergoing treatment for breast cancer. Tidying their discarded clothes the morning after, Ernaux ‘thought that this arrangement born of desire and accident, doomed to disappear, should be photographed’. Marie felt the same, and the results, a series of images of their crumpled, abandoned clothing mingled together on a series of bedroom, kitchen, and hotel room floors, inspired each to write a short response essay.

The Use of Photography is a book about sex and eroticism but death is ever-present in these images. Ernaux undergoes chemotherapy; Marie clears his recently deceased mother’s house; protests against the Iraq War thunder outside their bedroom sanctum. Eros and Thanatos are two sides of one coin. As Ernaux writes ‘If the shadow of nothingness, in one form or another, does not hover over writing…it doesn’t really contain anything of use to the living’. The photograph gestures at something beyond itself; sex, violence, death, comfort, illness, the many ways in which a body can disappear. They’re deeply moving, these images of absent bodies, of aftermath, particularly knowing that Marie died in 2022, the same year Ernaux won her Nobel Prize. Perhaps this elegiac quality is emphasised in the new Fitzcarraldo translation, which prints the photographs in black and white, rather than their original colours. The black and white renders them almost universal, symbolic images out-of-time (particularly the recurring, gendered shapes of boots and bras), whereas the candy coloured clothing and faded quality of the original film photos places them unmistakably in the early noughties. A photograph is ‘a hole through which the fixed light of time, of nothingness, is perceived’, Ernaux writes, and elsewhere, ‘a photo is finitude’. It holds a single moment, a moment defined by its before and after, a reminder of what did and did not occur, what cannot be returned to and reclaimed. Words, as Ernaux’s oeuvre has shown, are a way to return to those moments, and live them again.

My final read of the year, The Use of Photography drew together many of the threads I explored in literature over the last twelve months: gender relations, sex as a form of communication, art and the life of the artist, the relation between word and image. The way all roads of mind and heart seem to lead back to the body. Disappearance, absence, abstraction. Love.

Coda:

December Reread — The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

‘It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.’

A few days before the end of term, a friend asked a group at a dinner party what book we’d most like to reread for the first time. I said Titus Groan, the first of Mervyn Peake’s sombre and surreal trilogy about the gradual loss of childhood innocence and imagination, set in a sprawlingly archaic and fantastical estate like something out of a Chirico painting. I should have said The Little Prince, by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, which I found tucked away on my parents’ bookshelves when I returned home for the holidays, alongside the Moomin books, another good contender for a Christmas reread. I sat on the attic floor, where I used to creep away to read as a child, and reread the whole of The Little Prince. By the time I’d reached the section with the fox who just wants to be tamed (read: befriended, read: known) I had tears rolling down my face. This line, a reminder that the most important things are often the least visible — like a sheep in a box, or a singular rose on a far-off planet, or the little prince who tends that rose, or love itself — is one I will carry with me into 2025 and beyond.

Have a Happy New Year, and my love and hope for 2025.

H x

P.S. My debut pamphlet, SEA GLASS(ES), came out earlier in December from the incredibly cool new micropress Tallfinger Press. Two essays on time and place, ranging from a psychogeographical encounter in St James’s Park to crossing the Atlantic Ocean and family history; SEA GLASS(ES) is now available online and in selected bookstores. If you’d like to support my work but can’t afford a paid subscription, or just want something physical as a New Year’s treat, I’d love if you picked up a copy. Otherwise, paid subscriptions are as little as £2 a month, and are really, hugely appreciated.

A few disclaimers: This list starts in March, when I began carrying a pocket notebook everywhere. Doing so has been an excellent practice and I highly recommend you adopt it in 2025! This post has been seriously threatened by my abysmal handwriting, so any transcription errors are my fault at the time, as I’m copying the passages from my own notes, rather than the texts. Bad academic practice, but this is, after all, a blog. And finally, this is by no means the books I found most influential or enjoyable this year, but a fairly random sampling from across the months.

My own also, which I will accept probably explains part of the appeal of this novel.

The review will be out in the New Year, I’ll share it on here at some point.

I refer you also to Dr Ally Louks, one of this year’s greatest posters and unexpected internet survivors. I hope to be the Dr Ally Louks of 2027.

You can learn more about my historical research on my website here.

‘Maybe I’m already incubating the throat infection which will throw off the rest of my term’ I feel that 😞

Interesting idea! What got you interested in learning Greek?