social media, shame, spectacle

almond moms and almond brides and how is any of this actually helping anyone?

TW. Eating disorders (again)

If you’ve spent any time online in the past few weeks, you've probably encountered last month’s main character of the internet: influencer Sam Cutler whose ‘everything I ate at my wedding’ TikTok went viral when it was reposted with the caption ‘ED wedding’. What followed was a digital feeding frenzy, as strangers and terminally online opinion-havers dissected every second of the one minute video. What was on offer for guests, how many bites of each dish the bride took, the size of the plates. Very quickly, the tone became hysterical, condemnatory. ‘I bet she didn’t even eat the salmon’, one commentator snarked, as others gloated that her guests would all have diarrhoea because of the presence of ‘laxatives’ on the tables (anti-bloat pills including a digestive enzyme designed for IBS sufferers). The vindictiveness with which absolute strangers were approaching an innocent woman’s TikTok — about her wedding, of all things — was shocking. Yet it wasn’t surprising.

In an age when reality TV has become predictable, hotly anticipated dramas drop episodes en masse and are forgotten within the week, and social media feeds are factory production lines of identikit influences, the hottest new form of entertainment is other people. Specifically, unsuspecting other people. Whether it’s a mic in your face, a public ‘prankster’, or a bored doomscroller looking for the next viral moment, our daily lives are no longer just ours.

This particular viral pile-on hit home with me, in part because it reminded me of my own experiences. One of my most vivid school memories is an older girl pausing in the common room doorway and glaring at me with utter contempt. I can’t remember what it was she was saying, but I remember how it ended — she’s just anorexic anyway. It was the first time anyone had even suggested my behaviours around food weren’t right or healthy, but it wasn’t said from a place of concern or kindness. It was an insult barely spoken to my face.

I couldn’t stop thinking about that interaction as hot take after hot take about the ‘ED wedding’ made its way across my feed. The way it made me feel small and confused, the way it made me double down on food, because I had a point to prove — that there was absolutely nothing sick about me. Denial is a symptom of eating disorders. It’s also a coping mechanism. When someone is shouting in your face that there’s something wrong with you, there’s nothing you want more than to retreat into the thing that makes you feel safe, feel in control, whether that’s weighing out your portions or searching obsessively for ‘clean’ ingredients. It’s one of the (many) issues I have with the current therapy system in the UK; often, diagnosis feels less like an effort to help you recover than someone yelling at you that you’re fucking up.

The reaction to Cutler’s wedding was about as far away from therapy as you could get, yet everyone seemed determined to diagnose her with no awareness of her circumstances bar a one minute video. In fact, a follow up video showed the variety of food on offer at the event, and discussed the couple’s efforts to make it inclusive for dietary restrictions and allergies.1 She also clarified that the bloat pills were available to guests with full information provided, and were not ‘forced' on anyone. The event looked fancy, well-catered, and maybe a little Erewhon-core, but it’s the wedding of a LA-based fitness blogger — what else are you expecting? Just because someone chooses a (ostensibly) healthier option, it doesn’t mean they have an eating disorder. And it certainly isn’t okay to make fun of or shame them for it.

If you’re a woman who knows someone who’s got married, has planned or even thought about your own wedding, you’ll have been exposed to the harmful messaging around eating at weddings. Diets, meal plans, workout programs, special massage treatments designed to make you look thinner, dresses bought a size too small… The whole bridal industry is built around looking perfect, not looking like yourself, and a huge part of that traditionally involves food restriction. Attacking one person won’t change that. In fact, a professional wedding planner said on TikTok that she was surprised by the amount of food Cutler included at her wedding — ‘she ate more that I’ve seen almost any bride eat’.2 There is definitely something to be said about using your wedding as an excuse for product placement, the unrealistic and often harmful expectations wealthy fitness bloggers set for ordinary people, and the problematic nature of 'what I eat in a day’ videos in general, but that wasn’t the form criticism took. People seemed more interested in tearing down and picking apart one individual's entire life, rather than considering the wider context or the actual person on the receiving end of thousands of cruel comments.

I wish people would call it what it is — bullying. Sure, putting something online invites comment, but unless the content is actively harmful, viewers should exercise an element of caution. This isn't a TV show, it’s someone’s life — someone who you readily acknowledge might be struggling. Not to sound like an internet safety lesson from 2010, but people online are real people. If that bride does have an eating disorder, diagnosed or not, the endless comments on her eating habits must be incredibly triggering. If she doesn’t, then she’s certainly been forced to think about her food intake more than she probably ever has before, as thousands of people obsessively analyse her every bite. Either way, the memories of her wedding day must be irrevocably tainted. It’s not healthy for the commentators too — constantly thinking about the bodies and eating habits of others is in itself a sign of a disordered relationship to food. That constant mental commentary is something I’m still unlearning, not to stare at other girls in the gym or note when someone’s lost weight, equal parts horror and longing in my heart. In my own recovery, I’ve learnt to interrogate my thoughts, to reflect on my biases and where they come from. But the internet — 280 characters, twenty seconds of typing, hit tweet — has an inbuilt aversion to reflection and self-interrogation.

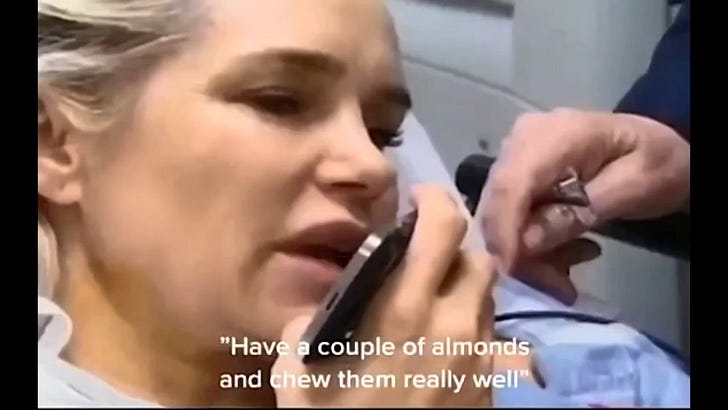

Several comments labelled the woman an ‘almond bride’, a reference to the ‘almond mom’ trope. ‘Almond mom’ refers to a mother hooked on diet culture, suffering from an internalised fatphobia that manifests in her relationships with her daughters. Yolanda Hadid, who vies with Gwyneth Paltrow for the title of almond queen, famously told her supermodel daughter Gigi, then a teenager, to 'have a couple of almonds’ when she was feeling faint.3

Disordered eating is a generational cycle, passed on from mother to daughter through thoughtless and toxic comments. ‘Almond mom’ can be a useful phrase to help women make sense of and break this cycle, but recent iterations of the trend have taken a darker turn. Videos titled ‘pranking our almond mom’ involves ordering ‘unhealthy’ dishes and filming the woman's reaction. In one recent viral video, cheery music soundtracks the clips and the word ‘SHOCKED’ is emblazoned over the woman’s face as she shakes her head and recedes into herself.4 I wouldn’t say she looks shocked, I’d say she looks triggered, and terrified. The ‘almond mom’s’ behaviour may be harmful to herself and others, but these women are still people who are struggling and deserve support. Treating them as the butt of a joke might feel like healing, but how does it actually help anyone?

Why do so many recent viral moments involve poking fun at eating disorders? My personal theory is that, as the ‘almond mom’ trend suggests, we’ve all been hurt as a result of diet culture and the cultural acceptance of disordered eating behaviours. As 90s heroin chic and Y2K make a triumphant return, heralded by the new VS Angels, and Ozempic becomes the buzzword of the moment, we’re all a little scared. Online, under the cover of anonymity and cushioned by our filter bubbles, it’s easy to lash out at individual strangers who seem to epitomise the trend. And when we’re used to treating other people as content, it’s all too easy for valid criticism to slide into shame, mockery, or bullying. There’s a term for this — digilantism. Initially a part of online social activism, used to draw attention to unpunished crimes and injustices, digilantism refers to ‘people taking justice into their own hands, using the internet to punish those they feel are guilty or corrupt through surveillance, negative publicity, unwanted attention and repression’.5 This DIY social justice can help bring wrongdoers to justice, for example to name and shame celebrities accused of sexual assault, but it can shade into cyberbullying when bad or merely unpopular behaviour invites an unprecedented reaction.6 This has less to do with social justice than viewing people as content; when everything exists for consumption, doing something marginally wrong or socially unacceptable invites intensive scrutiny.

‘Online’ never just means ‘online’ anymore — if it ever did. Another recent controversy, involving a TikTokker who posted a video with two girls making fun of her in the background, highlighted the blurred lines between on and offline interaction. The epitome of digilantism, the girls were eventually doxxed, their workplaces and families inundated with furious strangers. One of them lost her job. Sure, the girls were mean, but were they really that mean? And was the original poster right to post their behaviour online, or even to film in a public setting without their consent anyway? Did other people have the right to comment — when did these strangers become free game? For people of an older generation, these questions — in fact, the whole episode — might feel irrelevant, irritatingly so. For those whose lives are intertwined with the internet, however, they can seem existentially important. How do you go about your life when you’re one video away from being the internet’s daily punching bag?

I wish I could end this post on a positive note, but I really do think the culture of the internet is growing ever more toxic. In our entertainment-saturated age, other people are the only spectacle that doesn’t get old. It seems that digilantism, doxxing, and good old fashioned shaming are here to stay.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

I highly recommend the Polyester Podcast’s episode ‘On Wednesdays We Dox Mean Girls on TikTok’, for a more detailed analysis of the trend.