phone noise

Towards a new body; or, What is this thing in my palm doing to me?

I am trying to quit my phone. I don’t have to tell you the symptoms of addiction I am suffering from, because you probably feel them too. You also reach for your phone between every set at the gym, and in the queue for the toilet or perhaps on it, and when you really should be working and when you get home at night. You have also deleted and redownloaded Twitter and Instagram and TikTok and possibly even Substack, you also click ‘one more minute’ and then ‘fifteen more minutes’ and then ‘ignore for today’. In fact, you are possibly doing that right now.

Both the eating disorder recovery community and the weight loss community talk about ‘food noise’, the persistent and overwhelming presence of thoughts about food. When food noise becomes obsessive it can be deeply detrimental to one’s physical and mental health. My own food noise is matched only by phone noise. The desire to pick it up. To know where it is. To touch it, look at it, open and close it and check it like some sort of archaic totem (really, what will the archeologists think?). I want to know what’s going on on inside the screen, even or perhaps especially when nothing actually is.

Phone noise is a constant static in my brain. It looks immaterial, but it is all-too solid, like the time-warped tesseract in the movie Interstellar, which the protagonist desperately hammers against. This wall of flickering, uneasy grey blocks my ability to think, feel, and act. I’ll be writing or working and my mind will cloud over, a miasma seeping into every crevice of my brain. My fingertips will itch. Sometimes this murk even hinders my ability to move; I’m sucked in, checking on autopilot, thirty Reels deep. When neuroscientists talk about ‘bedrotting’, a trend which began as a form of self-care, but which now appears as both sign and enabler of phone addiction, they talk about its physiological consequences, overwhelming our bodies with dopamine and eventually rendering us numb. After a high comes a low, and we hit total dopamine depletion, one of the effects of which is a sense of inanition, a physical inability to move away from the screen.

Not a lack of willpower but a numbness, an inability to move or motivate oneself into action, a potentially agonising psychosomatic struggle against the self. Bedrotting as Fuselian nightmare or Freudian fainting couch; not a trend but a symptom of social psychopathy. This is the antithesis of Virginia Woolf’s ecstatically romantic vision of the social isolation of the sickbed in ‘On Being Ill’. To be bedridden, for Woolf, is to be given a reprieve from the everyday warfare of modern society, to sieze the opportunity, ‘perhaps for the first time for years, to look round, to look up—to look, for example, at the sky’. This sick-sky is ‘shocking’, a revelation of both natural wonder and human insignificance. Indeed, even ‘if we were all laid prone, frozen, stiff, still the sky would be experimenting with its blues and golds.’1

Alone, in bed or on the sofa, with the tools of the digital world at our fingertips, we ought to be able to access Woolf’s dream of the bedridden artist. We are all frozen, but we are looking down, not up. One does not access the sublime on TikTok. The sky remains, an aimless artist outside our windows, uncaring and unobserved. Except for when we pause to take a picture.

We are more like the swooning woman in Fuseli’s famous painting of The Nightmare, trapped in bed by the monsters of her mind. The gargoyle on her chest is not a simple bad dream as we use the word today, easily dispelled by magnesium glycinate and the light of day, but a demon made flesh.2 In early modern Europe, the Nightmare was both a disease akin to modern sleep paralysis and a supernatural attack by a witch, demonic spirit, or the devil himself. Fuseli’s carousel horse head, eyes white and staring, is a nod to the condition’s etymology, although ‘mare’ in fact derived from the Old Norse mara: a malicious supernatural being, usually female, who oppressed the sleeper at night. (Early modern Nightmares were often blamed on witches.) The ‘Mare’ was a psychic tormentor, a diabolic seducer, and a medical condition. Yet it was ultimately nothing but air and dreams.

Fuseli’s Nightmare informs how I visualise phone noise. A literal sense of paralysis is one of the symptoms of our mass addiction to our phones. How can these tiny, insubstantial slivers of silicon and glass exert such a hold over us? The siren song of phone noise is near impossible to resist. It sinks into the substance of our selves.

What does it mean to be a human being when we spend so much time living through such a machine? If, as phenomenologists suggest, the embodied, acting, grasping self is our prime means of becoming in the world, then what does this subsumption into the static yet ever scrolling world of the screen mean for human existence? What does Merleau-Ponty’s I can mean when our relationship with space has become so lacking in external awareness or intentionality, so self-oriented and enclosed? Or to cherry pick my philosophical traditions, who cares for Cogito, Ergo Sum? Is I think therefore I am not meaningless when it is so easy to simply give up on thinking, to give up to the infinite, endlessly scrolling feed?

Historians and sociologists often debate grand shifts in human perception and use of time. From the rhythms of the liturgical calendar which structured premodern religiosity and festive release, to the impositions of the capitalist workday, and the untethered expansiveness of late capitalism’s project of the self, in which we all have the same 24 hours of the day to fill with our side hustles or to grind away in the vicissitudes of the gig economy. Time and technology are tied together; so is space. Think of the printing press, industrialisation, the ‘discovery’ of America, the Atom Bomb. Think how quick and close and crazy the world must have become, is still becoming. We live now in the time the World Wide Web wove for us. Global time, connected time, everywhere time. Nowhere time. Phone time.

In my day to day life, I live by phone time. I don’t know how to structure time, space, meaning, without my phone. I can’t navigate without Maps. I check my Notion Planner every fifteen minutes even though I know exactly what I need to do. My colour-coded calendar contains my life. And my boyfriend and best friends, including those I’ve met through the internet, live on the other end of a screen. What is this doing to me? What is it doing to my perception of my body, my mind, my individual subjectivity and my shared humanity? If time and space and selfhood knit and unravel in tandem with technological change, what is the immaterial-yet-strangely-physical condition of phone noise doing to the fabric of human reality?

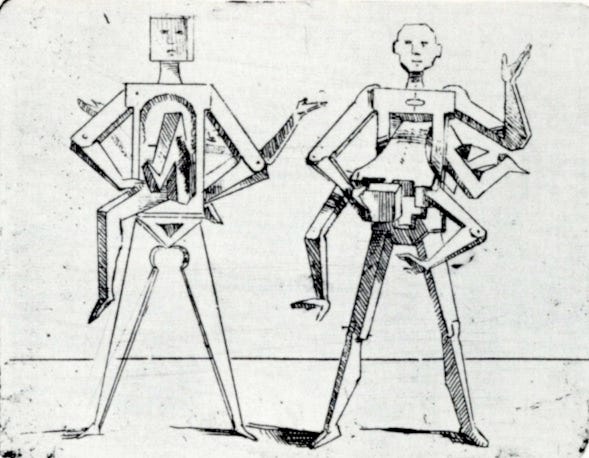

The seventeenth-century Florentine engraver Giovanni Battista Bracelli devoted part of his short life and career to what he called his Bizzaries. Published in collected edition in 1624, the Bizzarie di Varie Figure, or ‘Oddities of Various Figures’, appears startlingly modern. Crazy, contorted bodies formed of what look like compasses, and chain-links, and dented tin cans, these strange, pre-modern cyborgs are instantly captivating. There’s something delightfully whimsical about them, and at the same time, something terrifying. The Bizzaries contort themselves — or are contorted — for the viewer’s delight, a little like both the anatomical diagrams and freak shows which were becoming increasingly common in Bracelli’s lifetime. They rarely have developed faces; when they do, they never smile.

Bracelli was a more or less exact contemporary of the mathematician and philosopher René Descartes. I wonder what the Florentine artist knew of the French philosopher. His was an entirely new vision of the human form, one which, like Bracelli’s cyborgs, depicted the body as entirely mechanistic, as motion rather than motive. According to Descartes, the human soul was not trifurcated and dispersed throughout the body as the dominant understanding drawn from ancient authority suggested, but localised in the brain — the pineal gland, to be precise. The body, therefore, was not an integral, ensouled part of life, but a mere automaton, driven by the workings of the brain; an idea which would later be characterised as the ‘ghost in the machine’.

In one Bizzarie, Bracelli depicts two automata, posed as if in conversation. The second figure has a body trying to clamber through his stomach. He tumbles forwards, as if trying to escape. Is this the ghost, trying frantically to flee the prison of his body-machine? Descartes’ dualistic separation of mind and body would later be characterised as his ‘error’, a philosophical mistake with drastic consequences for human life (among them, the transformation of the Nightmare from psychosomatic experience to mere ‘bad dream’). I wonder whether it still holds true today. How do I envision the relation between my body and my soul or brain? I struggle to articulate it, because for most of my life, there has been a third party in that relationship. My phone.

Why Fuseli and Bracelli? Both these artists suggest that we are not — despite Descartes’ error — simply unchanging mental machines in constant motion through the world. Instead, we are shaped by social forces. What I take from Bracelli’s premodern cyborgs and Fuseli’s fusion of physical illness and diabolic influence is that our bodies are porous and perpetually open to culture, including the technologies we surround ourselves with and the narratives we construct about their utility. Could Bracelli have imagined his Bizzaries a hundred years prior, before the stirrings of the Scientific Revolution and the advent of Cartesian dualism, before the spread of guns and clocks and automata and the increasing mechanisation of life? Similarly, could Fuseli have painted The Nightmare a hundred years later, when the disease had been almost entirely stripped of its supernatural components, reduced to a mere ‘bad dream’? The ways in which these two artists envision the body still compel, delight, and unnerve us, but they are also highly contextualised, culturally-bounded if universally appealing. They are bodies born of particular moments in time.

What, then, of our bodies? The iPhone is seven years younger than I am, and in human years, AI is a toddler just discovering its own powers. Yet this nascent technology is reshaping our world and the way we experience it. It may even be impacting our evolutionary development. In 2022, researchers linked to a US technology company suggested that constant smartphone and computer usage will drastically alter the human body, with our descendants developing hunched backs, ‘tech neck’ and ‘tech claw’, a second eyelid to deal with blue light, as well as a thicker skull and smaller brain. ‘Mindy’, an exaggerated 3D mockup of these future humans, gropes forward in perpetual gloom, glazed eyes searching for a screen. Mindy is terrifying. She is pitiable. She is hiding inside each of us.

There are artists working today who capture this paradox. One is Ed Atkins, whose work is currently on display at Tate Britain. A British artist working primarily with animation and AI, much of Atkins’s work centres a series of computer-generated avatars, their features often modelled on his own face, isolated in hostile cyberscapes or or undergoing strange forms of torture. Strangely reminiscent of ‘Mindy’, these avatars have plastic bodies; simultaneously too hard and too malleable to be wholly human. They do not move quite right. They are deeply uncanny, and yet eerily relatable. In his multimedia installation Old Food, Atkins gestures both back to an imagined medieval past — a life which is nasty, brutish, and short — and forwards to our own technodystopia. Three characters, a plague-ridden, hunch-backed peasant, a richly dressed young boy, and a creepy overblown baby, float through a video game landscape loosely modelled on Europe in the Middle Ages. Each of them sobs and retches towards a piano, gloopy tears sliding down their too smooth faces, the melodies they eventually play haunting and disted.

In another piece, Hisser, an animated man modelled on Atkins falls through a sinkhole in the floor of his bedroom and into a blank no-place. Naked, terrified, he wanders this clinical setting alone. There is no escape for him, nor for us; once Hisser is finished, the videos loop. As Atkins is returned to his rumpled bed, curses slipping from his sleeping lips, I can’t help but think of bedrotting and its consequences.

The uncanny valley of Atkins’s work speaks to our current moment the way Fuseli and Bracelli once spoke to their’s. Atkins’s avatars are controlled not by an omnipotent God or the force of Nature, but by their programmer, the algorithm which drives their jerky motions, the technology which encloses them. They constantly reach towards us, encroaching on our sensibilities with their oozing, plastic bodies, but they can never break through the screen and escape. Unless we can free ourselves from our phones, they are, I fear, our future.

Ed Atkins is on at the Tate Britain until 25th August. ‘Hisser’ in particular reminds me of a piece I wrote in March on our current desire for digital dystopia, from Severance to the Backrooms. Find it here:

Enjoyed this essay but can’t afford a paid subscription? You can also show support with a one-off payment through Buy Me A Coffee.

Virginia Woolf, ‘On Being Ill’ (1925), p. 37. Thank you to my lovely reading group for a stimulating conversation about bedrotting via this text.

See, for example, Owen Davies, ‘The Nightmare Experience’ (2003)

What terrifies me about phone noise and phone addiction is how accepted it is. When I first told everyone I was getting rid of my social media they genuinely thought I was insane.

"not a lack of willpower but a numbness" -- THIS is the perfect articulation of phone noise and what it does to you.