creating spaces with alexandra coburn of alexandraleaving

what's on your desk and why does it matter?

Welcome to the second instalment of Creating Spaces, in which I speak to up-and-coming writers about what’s on their desks, the importance of writing places to them and the creative act, and the question of online vs offline space.

Creating Spaces was born of frustration with the way we aestheticise the writer’s life online, as well as an abiding curiosity with the conditions in which we create art. Inspired by Virginia Woolf’s argument that ‘a woman must have money and a room of her own’ to write, the rise of ‘literary it-girls’ and ‘thought daughters’, as well a desire to unpick the hyper-stylised ‘what’s in my bag’ trend, Creating Spaces looks beyond the visual appeal of the writer’s desk to its lived experiences.

My second guest is Alexandra Coburn, a writer and film programmer from NYC who writes the blog Alexandra Leaving. You might have read Alex’s recent post ‘cut piece 2024’, in which she analyses Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece performance in order to discuss the onus of vulnerability and the confessional placed on women writers online. The piece is a much-needed reflection on online writing at a time when navel-gazing about Substack is in vogue (see the recent discourse!), so I went into our call keen to unpick some of those threads.

Like Millie, who I spoke with in the first Creating Spaces, Alex is preoccupied with memory, recall, and nostalgia. Her voice is warm and witty, and I enjoy her thoughtful, clever writing so much I can just about forgive her for being a New Yorker. I hope you enjoy this conversation — which takes in writing on the internet, minimalism versus maximalism, and the strange power of the Substack font — as much as I did.

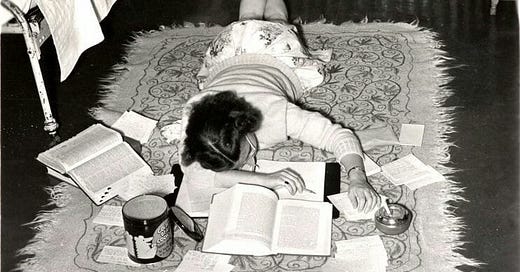

HELENA: First of all, just looking at this photo, what’s on your desk?

ALEX: Because I live in New York, in a tiny apartment, my desk is just my nightstand. And I always keep pens on my nightstand. I have like four different notebooks, and then I like to keep my books on hand. I think I have some of my favourites, like Rachel Kushner’s The Flamethrowers, Tom Wolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities, things that I feel sort of inspire my writing ethos. And I also have a little stand I got off the sidewalk, which has these Renaissance angels on it, and it’s where I keep all the ephemera my penpal Annie has sent me. We’ve been penpals for several years and all of that stuff is very inspiring because I think I’m someone who’s constantly writing about memory, nostalgia, all that, so being around these objects and letters, things from people who were writing letters in the 60s, or just bookmarks or tiny receipts… I’m a big tchotchke person and my desk is full of tchotchkes. I love tiny memory objects.

HELENA: I’ve actually written down the words ‘physical ephemera’ about your desk photo. I was wondering whether having those physical artefacts in your space inspires you when you’re working? I always want to keep things like ticket stubs and gallery guides, because I convince myself that one day I’ll find them useful or interesting or write about them, but quite often they end up as clutter. How do they inform your practice?

ALEX: I think its hard because on one hand they are clutter, in a literal definition, but I also think being around them… I’m trying to think if I’ve ever written about certain things I have near me… I think the actual physical little drawer, to me, it’s something I go through when I need to take a pause from the internality of writing. I think I analyse my own thoughts obsessively in a way that is very obvious in my writing, but I try to avoid the pull of narcissism! I also like being able to take yourself out, read the exchanges. The letters people wrote me are in there and I love to re-read them. I don’t know if that’s like, masochism or love, or whatever, but I love to read letters that I wrote with people. That’s just one box — there are boxes stock full out of site because I used to have a bunch of penpals and also I encourage people in my life to write me letters. I love writing cards, that’s one of my favourite things, so that’s the vehicle or vestibule for that… I don’t know, that’s very inspiring. They take me back to certain places. My current piece I’m working on is about memory, time travel and past fixations, so that is probably a huge reason why its so easy to fall back on those patterns. But I don’t think its a bad thing.

HELENA: No, definitely not.

ALEX: I think I’ve talked about how I worked in an archive for a couple years, and that has made me obsessed with keeping things. I’ve become a hoarder. I don’t have enough space to be a proper hoarder but I think if I did it would be the most cluttered rococo maximalist space in the world, because I cannot get rid of things.

HELENA: I went recently to Charleston, Vanessa Bell’s house in Sussex in the UK, and there were maybe a hundred watercolour-painted lever arch files lined up on the bookshelf, and each of them was labelled with a year’s worth of letters, and I wanted so badly to know what was inside of them. Though it’s probably now archived. I guess it’s having that stuff in your space — the past feels more present than if you’re just looking into the black mirror of your laptop screen.

ALEX: I think I used to shy away from being sentimental but I’ve come to terms with the fact that I’m a deeply sentimental person. When I was working in an archive I was reading through letters from the 1970s downtown New York art and film scene, and reading those letters was so touching because a lot of those people had died, because that was a period when New York was losing artists at such an intense rate to drug addiction, AIDS, governmental refusal to act on those things. Just to have those objects, to be holding a postcard from Basquiat, it made me superstitious about keeping everything.

HELENA: This series is partly about the ways the space in which you work reflects the output that you’re creating in that space. I was thinking your tchotchkes and ephemera are sort of anti-minimalism in a way. There’s a really good Becca Rothfield essay about decluttering, and she talks about how minimalists advocate tearing out the pages of books you find profound and discarding the book itself, just keeping the quote itself in a folder. When I read that it made me feel physically ill, but in another way, it’s just another form of hoarding. I was wondering if you had any thoughts about different forms of art emerging from different spaces.

ALEX: Yeah. Now you’re saying that, I wasn’t thinking about it in that way, but my favourite writer is Nabokov, who’s known for being a huge maximalist, purple prose everywhere. And I think I can be purple prose-y.

HELENA: Oh same, same.

ALEX: I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that personally, I’m over the whole dry millennial malaise tone, although it has its place. But Nabokov was also a collector, he was a lepidopterist and collected butterflies, and his wife was a de facto archivist, she kept all their correspondence, and all the correspondence between him and Kubrick when they were adapting Lolita. They as a couple were amassing this stuff which eventually got donated to the Cornell Library, which was a massive resource for me when I was writing my thesis on Nabokov. But I think that similar to him, not only am I a huge maximalist but everything I write is refracted through the lens of memory. I’m not a futurist at all, I think almost everything I’ve posted is about memory and recall, and I think that’s the impact of having been obsessed with Nabokov as a teenager and the way that he was able to conjure these memories that felt kind of universal, especially when he’s writing the American countryside in Lolita. That was a huge catalyst for my writing.

HELENA: In your work you definitely get a sense of the retrospect, the processing over and making anew of a memory. I’m interested you mention that dry millennial style, because I think it has a counterpart in some of the self help literature or popular non-fiction, like The Body Keeps The Score. What I think of as airport books!

ALEX: Oh God, I will never read that book.

HELENA: Neither. I think those books reflect the minimalist aesthetic in way, because they’re so stripped back, they only exist in the present and future tense, not the past — or if the past is there, like in The Body Keeps The Score, it only exists for the creation of the present-future.

ALEX: I think there’s a reason I really resist that ‘HR-ification’ of everything, where everything gets desexed, defanged. I love messy, disgusting, abject feelings! And I think about that millennial fiction especially, that dry, futureless fiction… I think it’s so to do with the post-9/11 doomer mentality, sort of where is this going. And I think my favourite writing resists that tendency and creates a place that’s away from that realism. I think deflationary realism works but I like my realism a bit hysterical, a bit heightened, and less so it feels like I’m reading an email.

HELENA: I was thinking about Sally Rooney, and obviously Normal People has so many emails in it. And I love that book! I guess maybe its popularity speaks to that sense of looking into the future and seeing this blank and the past being almost too freighted to open up. She’s a master of that bare style but when she’s imitated it doesn’t always work so well.

ALEX: I think she’s one of the few writers who can do that and it doesn’t feel hopelessly deflated. She has these beautiful piercing sentences that take you out of the deflation. I think a lot of my favourite writers were writing during the New Journalism movement in the 60s and 70s, and I think they took these serious situations and bought a sense of levity and absurdity, and that has always been my way of dealing with writing creative nonfiction. There’s something freeing about seeing the absurdity in things, or seeing the patterns and pointing them out.

HELENA: I think this goes back to the ephemera and the entanglements, because for me that’s why I like creative nonfiction as a genre. It illustrates how messy and confused life is, and that’s quite antithetical to the minimalist aesthetic.

ALEX: I recently finished How To Survive Safely In A Science Fiction Universe by Charles Yu, who wrote Interior Chinatown. The book is about the idea that if we ever time travelled we would all do things exactly the same, and there’s something beautiful about that idea that we can’t change the future. He says there’s a small gap between determinism and free will but in that gap is where we can build something liveable. To paraphrase, he says, as people we’re hurtling towards a future whilst looking backwards. I think my writing feels like that a lot. There’s something irressistible about returning to the past, and when I’m surrounded by reminders of the past it’s hard no to look that way. Maybe that’s also why I collect stamps, these little teeny worlds, a glimpse into the past. I’m a very retrospective nostalgic person!

HELENA: So back to the desk, I see you have a typewriter. I was wondering if you use that, and what the significance that holds for you is? Because I have my dad’s old typewriter, which he gave me as a teen, and I think I maybe wrote three poems on it just for the purposes of posting them on Instagram, which is embarrassing to admit.

ALEX: So I did used to use it more frequently, when I was writing letters. My roommates used to say they’d hear me click-clacking. I enjoyed it, it makes you slow down because it’s so cumbersome. When I got it, at the time I was really into the Beat Movement and I would think about Jack Kerouac carrying around his typewriter and cranking out thousands of words… I love to make things a little difficult for myself, so I think the typewriter was a way of doing that. Now it’s become an object that means so much more than just the physical object, it reminds me of so many different people in my life.

HELENA: I guess it’s like the letters, it holds the memory in the keys, which is less clear with a laptop. I wanted to talk a bit about analogue versus digital writing and making space online. Because the slowing down on the typewriter, or by hand in a notebook, is a different sort of writing to writing straight into the Substack editor on your laptop, where you’re touch-typing, its really quick and pacy and you feel the pressure of that very fast medium. Especially as Substack becomes more social media driven. Thinking about your ‘cut piece’ essay, and the idea of vulnerability, I’ve come see that mode of writing as a bit of a trap for young women in particular.

ALEX: It’s funny you bring this up, because this is integral to my writing process. For the most part, a lot of my writing originates in a physical notebook and then I transcribe it, because in the transcription you understand what you want to share and what you just wrote on the train that doesn’t necessarily need to see an audience. I think I write by hand because not only are there less distractions, but also so much of my writing is done in transit, and I like that having that extra barrier. When you’re writing in a journal you can jot it down, and my writing can be pretty unintelligible, but its the transcription process you put on the lens of what do I want to share with the world. It’s so crazy how when you’re younger you just don’t believe this is true, that the internet is forever, and you don’t want to share everything, and when I was twenty-one or twenty-two I was much more willing to expose myself online. And now that I’m in my mid-twenties, I feel like the auto-didacticism of opening the Substack editor– though there is something about the editor, I will say, that sometimes I find myself really cranking through it on there–

HELENA: I think it’s the font! I really like the font on there.

ALEX: It’s the font! The font is good. There’s just something about it. I feel more inspired staring at the Substack editor than a Google Doc. But I think Substack lures you into this sense of ‘this is your journal, this is your blog, this is your Tumblr’, and its not! I think if you have any sort of audience, like more than a hundred people looking at your work, you should probably be careful. And I think that’s part of why when I was writing my novel this year, I wrote it in a notebook and then transcribed it, because it’s extremely personal, and I wanted to make sure I was creating a bit of distance between the fiction and the autofiction. It does make me really nervous, as I said in ‘cut piece’. There’s something brave about putting yourself out there in such a raw way but also you have to protect your autonomy. The idea that especially men could be reading my writing and feeling like they knew me really got under my skin.

HELENA: I’ve had this conversation with other writers and I think it's a really common feeling among those who have unexpectedly hit a certain number of followers, that question of accessibility to you as well as your work. What also worries me is that with the physical artefact of a journal on your desk you can lock it away or hide it, and I know when I was putting personal stuff on Tumblr as a teenager, it was anonymous. I had a few in-person followers but it certainly wasn’t in my full legal name. I guess it’s exactly what we as kids were taught in the noughties about stranger danger but it has taken me way too long to actually learn those lessons — I really felt this when my essay got a lot of attention earlier this year.

ALEX: I don’t know if you felt this way when your essay went viral, but it’s very strange to watch people interpret your work. It’s really bizarre to watch people interpret your work, not wrong, but in bad faith.

HELENA: Disingenuously.

ALEX: Disingenuous, yeah. And from people who maybe didn’t even read it. I think I’ve got over that feeling a little bit, but it’s still in the back of my mind. I know we both are or were in academia, and it does feel like when you’re trying to build a professional name for yourself and you want to do something with your writing beyond the internet, there’s always a fear that some editor is going to find a Substack piece you wrote. It’s very strange.

HELENA: It makes you much more aware of what you talk about in ‘cut piece’, the onus of accessibility which lies on women in particular. Though we could definitely keep talking about this, I feel that this a good point to move onto my final question, which takes us away from the desktop and back to the desk. If you could visit any writer’s desk throughout time and space, whose would it be and why?

ALEX: I knew this question was coming, because I read your other conversation, and I was like I’m going to have a great final answer! But I think ultimately, and I already talked about him, it would be Nabokov. Whenever I’m writing and I feel uninspired, I reread him because I need to remember what really good prose looks like. And I also know that he was a maximalist, a hoarder, and that his desk was probably quite interesting. There were probably butterfly carcasses, and butterflies pinned to boards, and his letters. I think his intersections and interests, I align with. He was interested in film, and aesthetics, and art, and he was a very well-rounded person. So visiting his desk would be a very inspirational moment. And I think seeing his letters to Vera, Vera’s letters to him, seeing those in person would be really special. I was hoping I would come up with a more obscure answer, but honestly, that’s just my true answer.

HELENA: I always feel I know the answer I’m going to get, because it is that person who inspires you. Mine is, very predictably, Virginia Woolf. It’s an interesting question because it makes you think not just about that person but about their influence on you. So no, a great answer!

You can find Alex on Substack and Twitter @alxndra1998.

Twenty-first century demoniac is a reader supported publication. I love being able to have conversations like this one and create new work for the blog, but my work is reliant on paid and free subscribers. Please do consider pledging your support today!

You can find the first instalment of Creating Spaces here:

creating spaces with millie jacoby of the dybbuk diaries

I am so excited to welcome you to the first instalment of Creating Spaces. In this new series for Twenty-first Century Demoniac, I speak to up-and-coming writers about what’s on their desks, the importance of writing places to them and the creative act, and the question of online vs offline space.

This is lovely. I worked in an archive too, and it gave me this sense of reverence about even ephemera. Because everyday scraps of paper or working notebooks are kind of the stuff of life. They’re where we live in the moment. So I always feel like the survival of those things is a bit of a miracle. Which makes me keep everything.