Wrote this in the summer, after seeing ‘Michelangelo: the last decades’ at the British Museum, which has now ended, and then forgot about it.

D. is drawing me. He is in his armchair, I am sat at an angle, in one of the hard wooden table chairs, which are mismatched but all the same wood, russet-brown in the light, like an old spaniel. I have fetched his coat in from outside, the shaggy black fleece hanging over the back of his chair, another faithful dog. The actual dog pads to and fro, sneezing occasionally, with his greying hair and the stately paws of a sculpted lion he has the aura of wisdom, but not wit. I know I am being drawn, though I think D. has intended surreptitiousness. He has angled the iPad away from my eyes so at first I thought he was checking something — I don’t know what, perhaps the weather. Though D. does not strike me as someone who checks the weather. With his sprawling garden, its runner beans and climbing roses, I think he encounters it each morning and accepts it as it is.

Sitting here, performing stillness, I remember a visit to the house of Cézanne, in Aix en Provence. The vast window the artist had built, the slot for passing paintings through, so better to work on those vast canvases en plein air. Funny, to remember so suddenly that the Impressionists and their successors were radical. I wanted to clamber through it, that gap which opened onto the garden beyond, and into a different world.

I am trying to be nonchalant about being drawn. It is a little difficult, now I have noticed the act, and thus become implicated in it. I am not a natural model. I am awkward in my skin and wave my hands about as I talk. All this gesticulating serves a purpose. I am trying to explain my research, something I’ve been driving at all afternoon, except we keep being interrupted by further arrivals, other guests. I too am a guest, but I want to call them unexpected. The red-faced man with the port-stained shirt, who guffawed at his own jokes; the slim woman sculptor; the fellow artist who talked and talked as if frantic to fill a silence that was not really there, unless perhaps somewhere within himself. The drawing legitimates this feeling of specialness, of having obtained some further status beyond guest and closer to — perhaps to companion. We always say the elderly require companions.

D. is drawing me but I would not go so far as to say muse or model. I am younger by decades than the other guests, who have blocked my gesticulations and convoluted explanations with their own indomitable personalities, but I am not quite that vain. And there is none of the formality, it is just a sketch. A sketch is just a note to oneself, I have heard artists say, a reminder on paper and nothing more.

So I am trying to be nonchalant about being drawn. I am avoiding peering over, I am giving him his space, trying to find my own. I am pretending I haven’t noticed, and trying to embody myself entirely so he can capture that, if that is what it is he wants to capture. I try to avoid also the impression that I am simply passing through, though I am hungry, and thinking of the bowl of unwashed cherries we left sat outside in the half-hearted summer heat, and thinking of dinner. I am trying to inhabit. He picks up the stylus and sets it down. I glimpse my eyebrows, the curve of my smile lines, my nose which is almost the same as his, such distant cousins though we are and divided by decades.

I talk and I talk. I let myself be observed. I try and observe in return. I remind myself that I have learnt — am learning — this art too late. This art of observation, which does not come to me easily. My last memories of D.’s partner, J., himself an artist, his shaking hands, the way memory glistens in his semi-absent eyes. We are leaving the house with the long garden and he says — Next time I see you I will tell you the story of that chair. It is a Polish chair, that I have been sitting on, a darker wood than the russet-brown, and small and low, with curves and carvings and poppy-red flowers. A chair from his childhood, I presume. It is a chair I picked in a flight of fancy, not just because I am the youngest, and lightest, and do not need armrests. When he dies I think of the chair instantly — that there will be no next time, that the story will go unheard, that I should have stayed, and I came too late. Here we are, unknowable creatures, and even to ourselves. This is the moment I begin to learn the art of observation, in the moment of death.

The same week as D. draws me, I watch a prominent female writer speak in a church, notice the way she picks at her empty ring finger, its reliquary of bones. I remember this more than anything she says, her intelligent remarks about form, and content, and the way she strives at the image in words. The influence upon her of her mother’s death. Instead I remember gesture, and the shape of her mouth, and I wonder if I will ever see D.’s sketch. I read years of practice in his fragile hands, the skin’s thin paper, translucent in the iPad’s upwards glow, and in the watercolour of an agapanthus on the table beside me. He hmms and mms at my ramblings which I know he is digesting what I am saying, though here I am simply shape and light and shadow. My noise moves the air just a fraction, alters the corners of my mouth. D.’s sketch is second nature, the same way the old dog puts his paws to the window and yearns. Spring is long gone, summer a poor showing. They have both seen it all before. Yet fingers and eyes find line anew and suddenly I feel I am the only one growing older.

A few weeks later I visit Michelangelo: the last decades at The British Museum. The British Museum, with its insistent and uncritical display of soft power, is a strange place for this subdued, sepia-toned show. Yet when we take the lift up into the rotunda business softens slightly, a half-hush. Dimly we adjust after the bright white. The exhibition guide informs us that we will see Michelangelo’s final works, the burning wick of genius. The vast preparatory cartoons and the sketched minutiae, which share paper space with to-do lists and receipts. The architectural blueprints and collaborations with proteges, the efforts and false-starts. All these luminous signs, which could so easily have been tossed away. These fragments.

The last room of the exhibition is a darkened antechamber, faded papers lit as jewels. Do the curators intend these walls, their not-quite-black, with fragment light, to speak to us of death? The reading is too gauche — though I am sure they do. I want in this space to slip out of the obvious. I think of candles flickering through veined eyelids, feathered closed for prayer. I think of kneeling and the pains of getting up, of what the absence of electric light would do. I think of darkness falling on a still warm afternoon, and the way men once slept and woke and slept under God’s heavy-lidded eye. I think of deteriorating sight, how my grandmother cooked for herself and baked for others, with her asbestos fingers and her swollen knees, as the shroud drew tighter across her sight. She made until she could make no more. I think of fire, and of D.’s hands. The hands which shake and shiver and still draw on.

At my grandmother’s funeral, I thought of her Bakewell tart, her Christmas cakes, the sticky white chocolate and apricot muffins. And I thought of all the times I refused to eat them. Art like food is a gift to both the giver and the given. Art like Michelangelo’s is genius, god-given, but it is also a ritual, a routine, an offering. Never more so than in these late works.

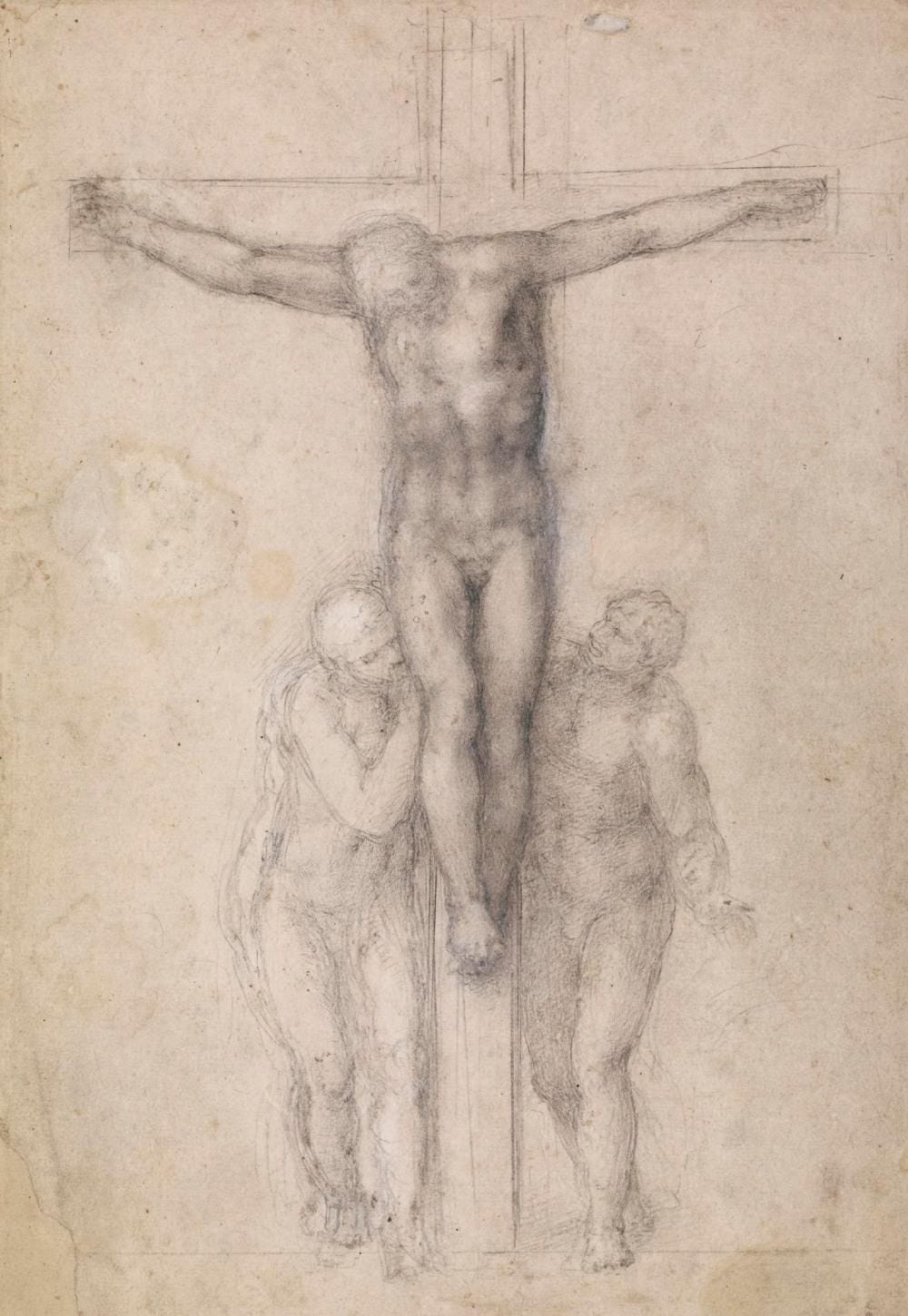

It is different, this last room, from what has come before. The pictures crowd in. Michelangelo’s lines grow looser, softer, his mark-making both curves inwards and radiates out, haloes the forms he coaxes from paper and pencil, wax and chalk. Muscular thighs grow lax, chests turn hollow. Everything softens, like the end of a day, the ragged seam of evening coming unstitched. If the eyes are visible they are closed; most often the whole face is a blur of marks, downturned, clouded. There is no definition, no clarity of line, yet these final sketchy works are the clearest in intention, far clearer than the striving fleshly warriors and the saints, the tumbling putti and wrathful gods. For Michelangelo there is always the body. Here it trembles under the weight of its past. I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free. Here is the angel, and there is no need to carve. A brush and a feather, time’s touch. Christ hangs from the cross and is at peace.

Again and again, the crucifixion, the pietà. The body at the same angle, the same shapes and shades. The same motions. Mark-making as meditation, the fingers down the rosary, the murmured words. The relic rubbed over and over to blur. These repeated images, finding their contours within himself. Compare to the earlier works, the straining of an Achilles tendon, a turned out toe, wide blue-sky eyes, the cords of an arched neck. To observe is first an active art, requires an education in the world. Later comes stillness, a turning in and the learning of peace.

I pause for a long time here beneath God’s eyelids. I could pause here longer. There is one image I am drawn back to, its overdrawn lines hazy, bodies made of shadow and light. Christ hangs from the cross, head heavy, face down-turned. The torso is long and still sturdy, the arms and feet peter into blurs. The body evokes a flayed écorché, but the hanging head and folded calves are peaceful. Yet the composition is unlike the others. At the base of the Christ-figure, which is disproportionately large, the Virgin Mary and St John the Evangelist press themselves to His legs and the wood of the cross. The contrast between the three bodies and the cross, purportedly drawn with a ruler due to Michelangelo’s unsteady hands, is stark, soft naked flesh against immovable harshness. That moment of touch — the raised hands, their clenched fists, the hunched shoulders, oppressive in their grief — that moment of touch is devastatingly intimate.

In the other renderings within the small dark space, the bodies of the onlookers do not touch. They recoil in absolute horror, in agony, in grief, in awe, but they are not implicated in death’s embrace. They are more conventional triptychs; characters, archetypes, saintly but not quite real, not quite human. But here the Virgin and the Evangelist are Mary and John, are man and woman, are mother and friend, are embodied humans lost in grief. Their forms quite literally lose themselves, traced over and over and in Mary’s case duplicated, so it seems she wears a long cloak, or the ghost of herself against her shoulders. It is in the tenderness of Mary’s touch, the hand pressed to her mouth and her son’s knee in wordless agony, where the drawing dissolves — dissolves both its subjects, its artist, and us, the viewer, so many hundreds of years on.

In this small dark room I think of the ars moriendi, the genre of devotional literature concerned with the art of dying, which gained such importance in Europe in the centuries following the desolations of the Black Death. Michelangelo would have known the ars moriendi, which urged the sick and dying to imitate Christ, to meditate upon his life, and to enter the darkness without fear. Yet he was afraid, the letters and sonnets in the exhibition prove it. ‘Neither painting nor sculpture will be able any / longer to calm my soul, now turned toward that divine love / that opened his arms on the cross to take us in’, he wrote, ten years before his death. As Edward Said wrote of ‘late style’ shortly before his own death in 2003, ‘There is an insistence in late style not on mere ageing, but on an increasing sense of apartness and exile and anachronism’.

This sense of exile which Said calls ‘lateness’ is there in Michelangelo’s words. But he did not turn away from art at all, as these final sketches and carvings and the poem itself prove. These acts of creation were also acts of meditation and preparation, an effort to ‘calm my soul’. That devastating scene of the crucifixion echoes the painting in its moment of embrace, the arms open ‘to take us in’. In this act of meditation does the dying artist identify himself with Jesus or the mourners? Or perhaps in the very act of decreation, of giving up the self. Ascension in descent and union in the moment of haptic encounter. The becoming and unbecoming of the body, in death, in touch, in work.

There are no paintings, in the house of Cézanne in Aix en Provence. They are elsewhere, scattered like cornflowers across Europe, the world. Whenever I see one, their mottled light and heavy physicality, I think of the house, its still life stage still set for tourists to gawk at, the long gone smell of turps and oil. These things we leave. What would it be like, to bring them all back? Not like a retrospective in a national museum, but a homecoming, a uniting. Those apples rolling off the canvas, Mont Sainte-Victoire looking out over itself looking out over itself looking out over itself.

Back at D.’s, the loose sunlight gives way to swathes of cloud, punctured by the odd spilt-ink ray. Summer is scarcely making an effort this year, but in the studio-kitchen-gallery we are surrounded by a hundred types of sky. This is what D. has painted in his later years, the sky at every time of day, its myriad musical variations, and foregrounded in cut-out black, the scenes of a quiet life in tandem with the world. I have two of these works already and I will take home a third, wrapped in plastic, the price tag peeled off and granted me free. It is sunset, an exploded rainbow seen through the hazy glass of evening, with a man and a dog in companionable silhouette. They make their way across a lamp-lit bridge, alone but far from lonely. The painting’s generosity makes me cry, it is so tender. Is the man with the dog the artist, or one the artist loves?

In the studio, being drawn and practicing my nascent art of observation in return, I wonder why we make art. And who for? I simply cannot take one — D.’s sculptor friend says when she drops by — My walls are too crammed with my friends’ art already. In late style, wrote Said, we see the ‘artist’s mature subjectivity, stripped of hubris and pomposity, unashamed either of its fallibility or of the modest assurance it has gained as a result of age and exile’.

At my grandmother’s funeral, we put together a trestle table of the arts and crafts she’d dedicated much of her leisure time to, which she’d made at community centre workshops and on cruises and in her spare moments. There were patchwork bags and photos of matching homemade dresses and flawless cross-stitch samplers and little woollen baby dolls, with oh-shaped eyes and tiny pink stitches for mouths. She’d gifted some to family and friends, displayed some in her bungalow, and stored the surplus in dusty cupboards, so that clearing out my mother and aunt found themselves inundated by tactile memories. We baked her mince pie recipe too, and left them on the table for guests to eat. My grandmother was not an artist, if to be an artist is to be original and to be great beyond words, to be genius. But writing this feels wrong, especially given the demeaning of women’s craft, and that of the elderly. She made things, did she not? She put herself into them, even when working from patterns and guidebooks and articles in weekly magazines, even when her hands shook. Like D.’s solitudinous sunsets, Michelangelo’s blurred meditations, these acts of creation were part of her self.

It was the table of crafts which finally overcame me at the funeral, which made me cry, those reunited lines of woollen dollies and carefully cross-stitched kitsch. A still life of a life. It was as if perspective had been discovered anew, and too late. The distance I had carefully constructed — from my grandmother’s life as much as from her death — collapsed in on itself. And so too did my idea of art, of what art is and why we do it. Where was grandeur, and scale, and fame in all this? As all the awe of the Sistine Chapel is condensed down into the tenderest touch, a kiss on the side of a dying son, the lines drawn and overdrawn and drawn again until they become the ghosts of themselves.

Back in the darkened room at the British Museum is an image of Michelangelo’s final work, the Rondanini Pietà. The mourning mother and the faceless son are half-hewn, still slumbering in marble. He dies and relives his birth lifeless in her arms, the body not yet fully carved out from her womb. Here is the flesh which fails to cohere, which fades and frays, but which is grief incarnate, over which the artist labours — if we can call it that — til the last days of his life, long into those grey hours. It is physically crude (there are no feet, no hands, and torn out eyes), but emotionally it is elevated above all else. Besides it his marble colossus, the masterpiece David, looks nothing but reconstituted dust. I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free. And is he now free?

Death rends us from the past and makes us more ourselves. Art, too, creates and dissolves us, all at once.